As China’s Economy Slows, Workers’ Anger Soars

As the demand for products from China has decreased due to increasing labor costs and declining capital investment, the closure of factories that employ many thousands of individuals has revealed a major deficiency in the Chinese market: the protection of the roughly 270 million migrant workers.

China’s stellar economic rise saw the increase of employment in the manufacturing and retail sectors. Spurred on by a growing middle class and a booming export economy, jobs were plentiful and the wages appeared to be ever increasing. Since 2006, the national average yearly wages for urban workers has grown by 273 percent, according to Trading Economics data. China’s three decades of growth has been driven by millions upon millions of new workers moving from the agricultural countryside to urban factories — factories that have been built on the back of government investments along with government funded infrastructure and heavy machinery.

That same engine of growth produces a paradox that has long been known to economists — an increase in education levels results in a decline in fertility rates, and therefore, declining population growth. In China, the problem was exacerbated by the “one child policy,” which artificially limited China’s population growth even before increasing wealth and education levels set in. According to a 2012 report by Accenture (updated in 2014), the Chinese working-age population may have already peaked. Adding to this problem has been the debt binge of the Chinese government, households, and corporations. The credit hole has quadrupled to 282 percent of GDP since 2007 according to a McKinsey report and has left country with a heavy debt repayment obligation.

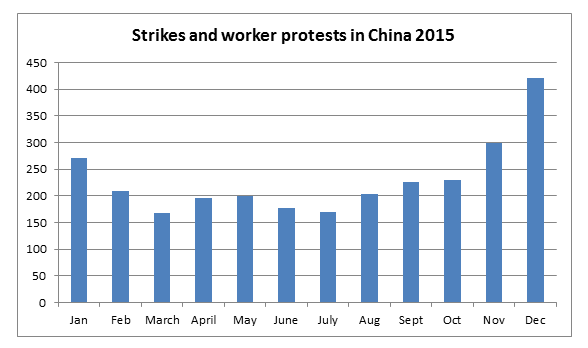

Chinese industry has a long-standing issue of non-payment, delayed, or partial payment of wages. The situation has worsened since the slowdown of the Chinese economy, and the levels of industrial dispute and protest has increased proportionately. The majority of these protests have been in the traditional manufacturing strongholds of southern China, in particular, the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong Province.

Chart source: China Labor Bulletin

In 2011, China introduced criminal sanctions for malicious non-payment of wages, but prosecution has remained elusive for the most part. In June 2015, Guangdong Province introduced draft legislation that could lead to employers facing criminal charges for failing to pay wages on time, or making unreasonable deductions from employee payments. These offenses would be punishable by fines of up to RMB200,000 ($30,670). However, little has been heard about this draft law since.

“I doubt they would be applied. Most of the new legislation and policy directives coming out of Guangdong this year are much more pro-business and anti-labor. The freezing of the minimum wage for the next two years is just one example of this,” said Geoffrey Crothall from the China Labor Bulletin. “Some local governments are seeking to criminalize worker protests for wage arrears; and as the government’s own survey of migrant workers shows, wage arrears have steadily increased over the last few years so the law is not having a deterrent effect.”

The official workers’ union body of China is the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (AFCTU), the world’s largest labor organization. Formed in 1925 under the Chinese Communist Party, it served as a mouthpiece for the Chinese people, and therefore for the government. However, since the liberalization of the economy and the privatization of enterprises, the AFCTU has faced an existential dilemma, according to the Global Labor University. Does it represent the people or government-sponsored enterprises? Unofficially, protests outside of the official AFCTU structure is seen as an attack on the government, for now.

By CAL WONG May 11, 2016 on The Diplomat

Read more here