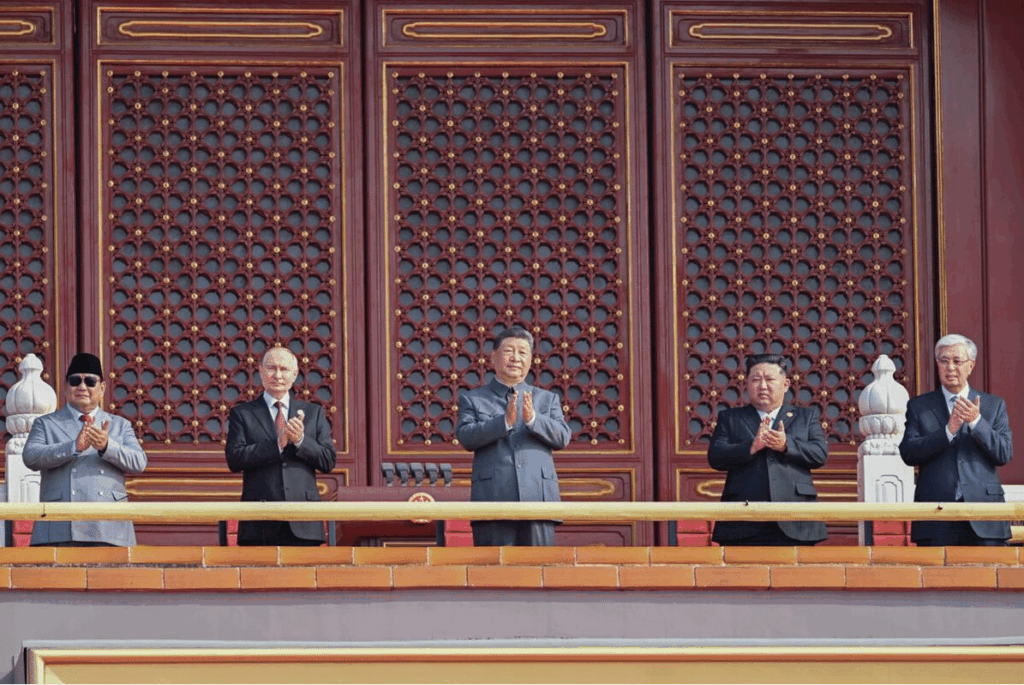

Xi Jinping (middle) between Vladimir Putin (left) and Kim Jong Un (right) at China’s Victory Day parade. September 3, 2025. Source

The relationship between the United States and the People’s Republic of China is host to a variety of flashpoints which drive interactions between the two superpowers. Two important ones among these are the Taiwan Strait and the Korean Peninsula. Both have a long history in terms of the U.S.-China relationship, and one that carries much weight today. With the bilateral relationship between Washington and Beijing in such tension, it is all the more important to understand and manage the parts Pyongyang, Taipei, and others have to play therein.

To better illuminate the tangle of connections concerning North Korea’s role in U.S.-China relations, The Monitor spoke with Dr. Shuxian Luo. Dr. Luo, author of the recent Foreign Affairs article “China’s North Korea Problem: How America Can Encourage Beijing to Rein in Pyongyang,” is an expert on Chinese foreign and security policy, Indo-Pacific regional dynamics, and maritime security. She is a veteran of several prominent organizations, including the Brookings Institute, the U.S. Naval War College, the Wilson Center, the German Marshall Fund, and the Council on Foreign Relations, and she currently teaches as an assistant professor at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. Tyler Quillen sat down with Dr. Luo to discuss her recent article and to gain her insights on the risks and opportunities surrounding North Korea.

Tyler Quillen: To start, could you briefly describe North Korea’s role in the U.S.-China relationship? How has it changed over time and where does it stand today?

Shuxian Luo: I think North Korea’s role in U.S.-China relations can be divided into two parts. On one hand, China’s dealings with North Korea serve as leverage in two ways. First, China uses its cooperation on the North Korean nuclear and missile issue as a bargaining chip to push the U.S. toward accommodating interests that China cares most about—usually Taiwan, but sometimes other issues as well. Taiwan has been the most consistent theme in China’s push for U.S. accommodation, whether in bilateral or multilateral settings.

When the situation becomes tense—when U.S.-China relations deteriorate and frictions intensify over how the U.S. handles its relationship with Taiwan—China will use North Korea as a counterbalance to whatever U.S. moves on Taiwan that Beijing perceives as threatening to its interests. More specifically, there have been writings by Chinese experts about the possibility that North Korea’s nuclear capabilities might be a useful asset to pin down U.S. forces on the peninsula during a Taiwan military contingency.

So, there are two ways that China tends to perceive the value of North Korea through the lens of U.S.-China relations, especially regarding Taiwan. That’s the overarching logic that China applies to North Korea in its dealings with the United States. It sounds a bit convoluted, but I think that’s what’s actually happening. I don’t see many other people or studies exploring this connection that China has maintained throughout three decades of negotiations on North Korea.

TQ: What are Beijing’s core interests when it comes to North Korea, and how do these compare against Washington’s? What explains the fluctuations in both nations’ track records regarding cooperation concerning North Korea?

SL: The conventional wisdom on China’s core interests regarding North Korea is: no war, no instability, and no nukes. That remains relatively stable and constant. That’s also the initial research question that drives my whole study—given that China’s core interests in North Korea have been pretty constant, what explains the variation in its approach toward North Korea?

We have seen periods where China cooperated with other countries like the United States and South Korea in pushing North Korea into multilateral negotiations like the Six-Party Talks, and also worked with the United States in working out new UN sanction measures and toughening those sanction measures. But more recently, China has taken an almost completely reversed approach—blocking U.S.-sponsored UN sanction measures, and so on and so forth. China has switched from a more cooperative approach with other regional stakeholders to a less cooperative one, more overtly condoning and shielding North Korea’s program in that regard.

So, the core interests still remain: no war, no instability, and no nukes on the Korean Peninsula. But there are other factors—key factors like China’s concerns about Taiwan and how China wants to use its leverage on the North Korea issue to push the United States into some sort of accommodation of China’s concerns about Taiwan. That has been a factor that drives the fluctuation, especially on the Chinese part, in its track record regarding cooperation on North Korea.

Of course, for Washington, I think the top priority is—and people debate whether it’s still realistic for the U.S. to push for this—the so-called CVID: Complete, Verifiable, Irreversible Denuclearization. Insofar as the U.S. still maintains this line, I would argue that’s the U.S. core interest regarding North Korea.

TQ: You mentioned this a bit before, but why is the issue of North Korea and its nuclear program so closely tied to that of Taiwan and Cross-Strait relations?

SL: That’s a great question. I think historically, in Chinese perception, these issues are related going back to the outbreak of the Korean War. I didn’t mention this in my Foreign Affairs article, but there is a historical background: the outbreak of the Korean War prevented China from carrying out its plan of so-called “liberating Taiwan”—or attacking Taiwan to completely end the Chinese Civil War back in 1950. China had to abandon that plan because of the outbreak of the war and the U.S. move to block the Taiwan Strait. So, there is this historical background that provides the foundation for China’s perceived linkage.

But in today’s context, in the contemporary post-Cold War context, it becomes more about what role North Korea might play in a Taiwan contingency. There are written sources, both in Chinese and English, suggesting that China might see North Korea as a potential asset in distracting U.S. military forces operating in the Western Pacific in the event of a Taiwan contingency. So, I think in that sense, that’s the most important way that the Chinese have been seeing a link and connection between North Korea’s nuclear assets and Taiwan Strait relations.

TQ: How do other nations in the region with vested interests concerning both North Korea and Taiwan, such as South Korea and Japan, view this issue linkage on the part of the U.S. and China?

SL: I’m not sure about Japan’s case, because I haven’t really dug into the Japanese perspective to see whether they perceive such a linkage, but in South Korea, they do worry about such a linkage, though it’s more in a reverse way. Some South Korean scholars I know have been working on a study that is precisely the other side of the coin. They worry that in the event of a Taiwan contingency, would North Korea exploit that window to launch an attack on South Korea? So basically, I’m arguing—and I think this is still in a preliminary stage—that there’s concern about whether, even short of an outright North Korean attack on South Korea, the United States in coping with a Taiwan contingency would push for implementation of strategic flexibility. By that I mean diverting part of, if not all of, the U.S. forces stationed on the Korean Peninsula toward Taiwan—into the Taiwan theater—in the event of a U.S.-China conflict over Taiwan.

So, there are tensions over the U.S.-South Korea alliance regarding what the U.S. has been pushing for: greater flexibility in using U.S. forces on the Korean Peninsula, not just confined to a North Korean scenario, but also available for something else in the region like Taiwan. That’s a concern, the potential for a North Korean opportunistic attack on South Korea is one concern, and the other concern is what the U.S. would do with regard to the Taiwan scenario, even short of a North Korea contingency

TQ: The second Trump administration has seen highly volatile and changing relations between the U.S. and China, sometimes uncharacteristically positive and other times more adversarial. With a possible Trump Xi summit on the horizon, is this likely to yield cooperation regarding North Korea?

SL: That’s a good question. I think that possibility remains, but I wouldn’t bet my money on it, especially because we’ve obviously seen all these fluctuations, particularly in trade friction and technology issues.

What I would argue for is a very precise one-to-one issue linkage—linking North Korea with Taiwan for the purpose of risk control and reducing the risk of military conflict in both regions. The logic is pretty simple: China can help rein in North Korea, although there are limits in terms of how far Beijing can go or is willing to go in reining in North Korea. In a similar case, though to a lesser extent, the United States can exercise some restraint on Taiwan, especially the current Taiwan administration, which is a real concern to Beijing. If Washington could signal that it can help restrain Taipei in that regard, I think that would be pretty desirable on China’s part.

But the thing is, it requires both sides to be able to compartmentalize these two issues—or this linkage—from other highly controversial, inflammable issues like trade, technology, rare earths, critical minerals, and so on and so forth. So I’m not sure, in terms of how the administration handles all these issues together, whether they would be willing or able—in terms of conducting very delicate diplomacy—to do some kind of compartmentalization.

Also, such issue linkage is pretty fragile because neither of the great powers can exert complete control over its smaller patron states. Both Taiwan and North Korea have their own agency. So, for the great powers—for example, if North Korea does something—the United States needs to be able to refrain from rushing to the conclusion that it’s a sign or manifestation that China has gone back to some uncooperative position. Similarly for China, if Taiwan does something that Beijing doesn’t like, Beijing needs to be able to refrain from rushing to the conclusion that the United States is backing Taiwan’s action that China doesn’t like.

So, both sides—that is to say, even if they can establish such an issue linkage strategy and compartmentalize it from other contentious issues—they need to be able to sustain this linkage with a degree of tolerance for imperfection, because part of it is beyond their control. I think both steps are critical, but I’m not sure—especially on the current Washington side—whether they can really manage to do that. One is compartmentalization, and the second is toleration for imperfection in any breakout, not reading every North Korea violation or provocation as necessarily being backed by Beijing.

TQ: Continuing on, if joint coordination to reduce the risk posed by North Korea does come to fruition, what form is it likely to take?

SL: I haven’t really thought about that question because I think even the previous question is so difficult, so it is not easy to imagine such a situation. But I think it should be something more like co-management, led by the United States in coordination with China, and also in coordination with South Korea. South Korea is especially important, given that the new government in South Korea has expressed a strong interest in restoring dialogue with North Korea—though North Korea is not showing any interest in talking to the South Korean government right now.

I think this forum could be something built upon the Six-Party Talks. Of course, many have demonstrated a quite sarcastic or ironic or critical approach toward the Six-Party Talks, calling it just empty talk that yielded an agreement that fell apart. But like I said before, I think no mechanism will be perfect, and the Six-Party Talks mechanism has been the mechanism that proved capable of producing some viable results.

Now there’s also the question of how far we can bring Russia aboard, but I think it really depends on which big power patron holds the greatest influence over North Korea—is it China or Russia? In the extreme case, if Russia decides not to cooperate and decides to stay out of this mechanism, can China alone still exercise some influence to bring North Korea into this framework? I think yes, because China is ultimately the most important supporter for North Korea. There’s no way that Russia can replace China in terms of providing economic aid or providing political and diplomatic space for North Korea in the international arena. So insofar as Beijing is determined to bring North Korea to the table, I think even without Russia back in the multilateral mechanism, it can still work. It could be Five-Party Talks or Four-Party Talks, and so on and so forth. It really depends on who becomes the next Japanese Prime Minister.

So, I think something modeled on the Six-Party Talks—with the U.S., China, and South Korea as the core parties to the whole Korean Peninsula issue—they can work out something together to co-manage the situation. That’s basically what I have in mind, but it’s a very rough picture as to what things could look like.

TQ: That feeds very well into my next question: What role does Russia play in terms of North Korea’s position in U.S.-China relations? How does Moscow’s ties with Pyongyang complicate efforts to coordinate between Washington and Beijing?

SL: I think that also comes down to how China will decide to leverage its relationship with both countries, because now there’s a lot of discussion and speculation about the trilateral relation—the tripartite interaction between Russia, China, and North Korea. One argument is saying that these three countries are forming a so-called “axis of autocracy” or “axis of upheaval”—that they’re forming a stronger, more consolidated anti-U.S., anti-Western bloc. But there are more questions and suspicions as to how solid that would actually look like. People question whether there is more distrust and misgivings between the three countries than appears on the surface.

So, I think Moscow’s ties with Pyongyang complicate efforts to some extent, like in terms of technology control and technology transfer. China can tighten its technology transfer—missile technology, drone technology—but Russia can just ignore that and go ahead. There’s been news about Russian technology transfer of missile defense systems and also training of North Korean military personnel in using drones during the war in Ukraine.

It also depends on whether Beijing wants to convey some pressure to Moscow in a way to curb Moscow as well. But again, Russia is also a great power that is very sensitive to its status as a great power. Even though some scholars and analysts will describe it as a junior partner in the China-Russia relationship, if China cannot exert complete control over North Korea, then how can China exert complete control or influence over Russia? Maybe Beijing can, to some extent, exercise some influence on Russia’s calculus, but I don’t think we should expect that China would go so far as to force Russia to completely comply with China’s expectations.

So yes, Russia will remain a complicating factor in these efforts, even if China is determined to exert some pressure on Russia. That is a wild card in this equation. I didn’t address Russia’s role in my piece, but I think Russia remains a wild card. There are also questions as to how far Russia can go—how much capability or how many resources Russia can provide to North Korea in a sustainable way, apart from some technology transfer and trade. In terms of economic resources, I don’t think Russia can be a sustainable lifeline support for North Korea in the same sense that China is.

TQ: I very much agree. Continuing the topic of the P.R.C. recently hosting the leaders of both Russia and North Korea for its World War II victory parade, how seriously should Washington take that trilateral relationship? Is this a solidified counter-Western bloc, or more a friendship of circumstance?

SL: I think it needs to be broken down into several parts, because it touches on three sets of bilateral relationships, and it’s not a simple matter of adding them into a trilateral thing, right? Yes, you have Putin, Xi Jinping, and Kim Jong Un watching this whole military parade together. That’s one thing—an open signal they want to send to the U.S. and Western audiences in showing their solidarity.

But on the other hand, as many analysts have pointed out, there was no trilateral summit happening between the three leaders. They basically met in bilateral settings. Also, I think Patricia Kim at Brookings just published a piece in Foreign Affairs and she’s spot on about all these historical misgivings and distrust between the three countries.

I would even make the counterargument that China has recently really started rebinding North Korea to its side in a quiet competition for influence over Pyongyang against Moscow. China and Russia have been competing for influence and, to some extent, a level of control over North Korea since the Cold War. So, it’s not necessarily that the three leaders standing side by side will culminate in a more enduring, ironclad bloc. It’s quite fluid.

Also, I think one reason that has been driving North Korea back to the embrace of China is Pyongyang’s anxiety about a potential change in Russia’s position after the end of the war in Ukraine. There has been wide discussion about how North Korea has been hedging its bets as well.

For China-Russia relations, it might be more enduring than the Russia-North Korea relationship because they have a structural problem with the United States—with the U.S. being a strategic competitor or adversary and the U.S. identifying both Russia and China as major revisionist powers that seek to overturn the U.S.-led international order. So, I think U.S.-China bonds will be more enduring—or more stable—comparatively insofar as Putin and Xi Jinping are in power. That will very likely outlive, the war in Ukraine and will continue into the near future.

But I think the North Korea-Russia part would be more uncertain. And for China and North Korea, I think it’s kind of part of this fluctuating bilateral relationship that we have seen over the past several decades. So now it seems it’s back to a little bit more positive dynamic, with the Chinese premier just recently visiting North Korea. Still, I think any warming up in China-North Korea relations will also be quite transactional.

TQ: Taking all this together, in terms of the larger U.S.-China relationship, is North Korea more of a liability or a useful common interest? How can the two parties use this issue and its possible linkage with others to better manage their own relations?

SL: That’s an excellent question. In terms of the ultimate objective, the two sides, the United States and China, share the same goal of denuclearization. Well, it still differs because China’s goal is denuclearization of the whole peninsula, and the United States’ goal is the denuclearization of North Korea. But there’s still something overlapping: the denuclearization of North Korea. So yes, in that sense, I think North Korea is still a useful common interest, but that’s on paper.

I think China issued a trilateral statement with Japan and South Korea back in 2024 reiterating that goal, and earlier this year the U.S. also issued a trilateral statement with South Korea and Japan reiterating the same goal. So, I think there are also shared, like-minded states—I mean South Korea and Japan—that can help bridge the gap and play a role in bringing the U.S. and China together on that regard, on the denuclearization of North Korea.

But that said, I think—how can the two parties use this issue and its possible linkage with others to better manage their own relations? Well, I think this issue, the North Korea issue, currently may not be on the same level of priority for China and the United States. The assumption of issue linkage is that the United States wants to achieve a goal on North Korea quite badly and sees that goal as pressing and important, and China wants something on the Taiwan issue and sees that as a pressing goal. So, in that setting, Taiwan and North Korea carry a similar weight for both sides, and that makes the linkage workable for both sides.

But now, Taiwan obviously carries far more weight than North Korea, and that makes it difficult because now North Korea is not a front-burner issue for the United States. So, I think I would have difficulty imagining how this linkage can work under current circumstances. Whether it’s possible to link it with other issues—I don’t think so. I think other issues are maybe creating more noise for management of these issues, like trade, like technology and rare earths. All these are creating noise that keeps distracting the two—the United States and China—from being able to really focus on reducing the risk for military conflict in these two flashpoints: the Korean Peninsula and the Taiwan Strait.

How they can better manage—I honestly don’t know, because the prioritization for the two countries has changed, and we don’t know in what direction it’s changing. Because North Korea, if we look at that issue alone, it is an important issue for both sides. But when we put it into the big picture of U.S.-China relations right now, it has obviously been put on the back burner. It’s really not a front-burner issue, and I don’t know how that linkage can be made to work right now.