A Speech by David M. Lampton: The Carter Legacy with China and Beyond

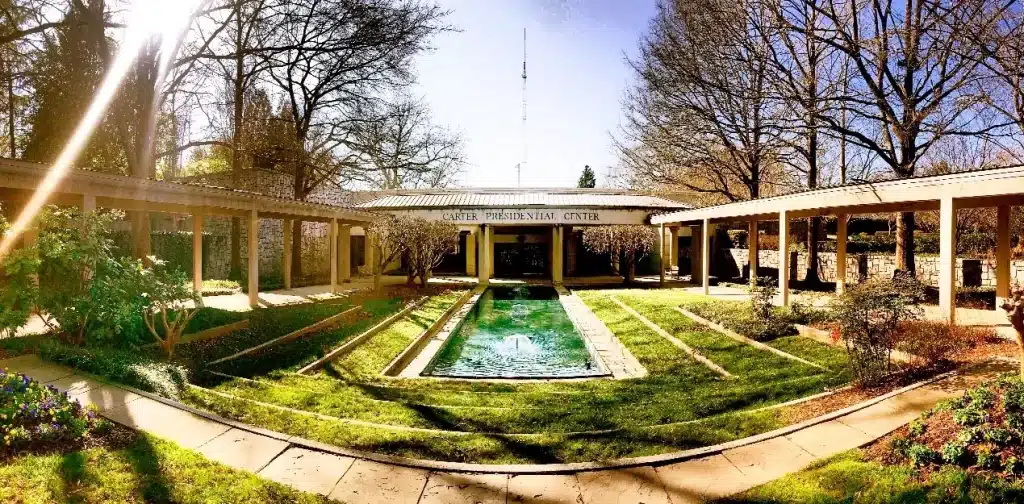

On January 9-10, 2024, the Carter Center held the Forum in Honor of Jimmy Carter and the 45th Anniversary of U.S.-China Relations. The event commemorated President Carter’s decision with Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping to normalize diplomatic relations between the U.S. and China in January 1979.

On the first day of the forum, the Carter Center hosted a panel called The Legacy of Engagement: The History & Controversy of U.S.-China Relations, featuring David M. Lampton (Professor Emeritus, Johns Hopkins SAIS), Jonathan Alter (Biographer of Jimmy Carter), and Susan Thornton (Senior Fellow, Yale Law School). The transcript below is Dr. Lampton’s remarks from the panel.

Good morning. It is a great honor to be part of this recognition of the Carters and their legacy on China, and indeed so much more. I want to thank Ambassador Xie Feng for his remarks and ask Carter Center CEO Paige Alexander to extend my thanks, and that of a grateful nation, to the Carters for “Waging Peace” all these years—And, not just with respect to China.

Before narrowing my focus to China, I want recognize the scale of President Carter’s ambitions and accomplishments. Considering simply the realm of foreign policy, President Carter brought a long relative peace to three strategic areas of the world with: The Panama Canal Treaty (1977); The Camp David Agreement (1978) between Egypt and Israel; and, of course, the reason we are here today, the normalization of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China effective January 1, 1979. In the latter bold move, he changed my life and the lives of everyone in this room. History has judged all three of these moves to have been wise, far-sighted.

One central thread to Jimmy Carter’s approach to China, as my panel colleague Jonathan Alter said in his biography of Jimmy Carter (His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life”, p. 421), has been that the president sees China as “evolving”, not frozen, believing that America’s best approach to that complex and ever-changing country is fostering positive voices and trends, finding common ground, implementing a policy of patience, and taking the long view. In normalizing formal ties with China, he was in a hurry to implement a policy grounded in patience and appealing to the better angels in our two societies. President Carter, initially, paid a political price for his policy of patience, but his wisdom has paid off handsomely for America, China, Asia, and the world during the 45 years since.

We once again need Jimmy Carter’s historical and developmental grounding, playing the long game, and doing so with empathy. Four elements of President Carter’s approach have served our nation and the world well and were evident in his administration’s China policy:

To start, in his autobiographies, and in the Jonathan Alter and Stuart Eizenstat biographies, it is clear that President Carter does not believe that problems get better from deferring hard decisions. From his earliest days in the presidency, Jimmy Carter said he wanted to complete the unfinished task of normalization with China soon after his election. At that time I assumed that was true, but that he would wait until his second term, thereby avoiding sizable electoral dangers. In late-1978, I was in Taipei doing a book and was winding up my research at the Institute of International Relations. The Institute’s head, Ambassador Tsai Wei-ping, asked me to come see him and say good-bye. In the course of our conversation, the ambassador asked whether President Carter would soon switch diplomatic relations to Beijing. Reflecting the then-current widespread analysis, I told Tsai that I thought President Carter would normalize, but not to do so until after the November 1980 election, given that the president would be vulnerable to attack were he to do so earlier. I was wrong. President Carter judged that waiting to do the right thing can fall victim to events beyond one’s control. Better to act taking the long view than wait for a future day that may never arrive.

A second aspect of President Carter’s approach to dealing with China was his belief that our national strategy should be building a society-to-society relationship, not just a state-to-state relationship held together by senior leaders in secretive summits. Rather, he wanted a thick fabric of inter-agency, locality, and non-governmental ties knitting the two societies together.

As it so happened, I was on the mission that President Carter dispatched to China in June 1979, a delegation headed by Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) Secretary Joseph Califano. This was the ninth cabinet-level visit dispatched by the president to the People’s Republic. In the course of the journey, under the umbrella of the S&T Agreement signed by President Carter and Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping on January 31, 1979, we signed health and education bilateral agreements that ignited the massive exchanges that followed. In the process, President Carter not only energized a wave of inter-agency agreements with China, he also stimulated local governments (such as Ohio where I then lived), educational institutions, and non-governmental organizations to build their own mutually beneficial relationships. Soon private sector and local activities and relationships dwarfed national programs.

A third feature of the Carter approach was that he was willing to take risks for peace, feeling that deterrence alone is insufficient to build a stable relationship. Trust is important and can be built in small and large ways. An example. In the course of preparing for our 1979 HEW trip, the issue arose as to whether or not there ought to be an undeclared CIA agent on the trip. Secretary Califano weighed-in against any such covert presence feeling that this ran contrary to the education and health ethos of openness and, more broadly, was not the way to build trust that was so necessary to set out on a new course with the PRC. President Carter emphatically backed Califano on this. The CIA did send an agent along on the trip, but he was openly declared and the Chinese did not object. At our farewell banquet, China’s Minister of Public Health, Qian Xinzhong, stood up, toasted the CIA agent, and expressed the hope that he found out everything he wanted to learn. Everyone laughed.

And a final dimension of the Carter approach was his willingness to live with ambiguity, and compromise where he could. What made normalization work was that both President Carter and Vice-Premier Deng agreed that they could live with ambiguity on key issues, including:

- The degree to which Beijing was committed to “peaceful resolution” of cross-Taiwan Strait issues;

- The exact meaning of “unofficial relations”;

- The exact meaning of the “One China Policy”;

- The exact meaning and scale of “defensive weapons” and arms sales.

It is true that living with these ambiguities left successive administrations in both countries with problems, but tolerably managing these ambiguities brought forty-five years of peace and enormous benefits to both sides, not least the absence of the hot wars of the Cold War that characterized the 1950s (Korea) and 1960s-1970s (Vietnam). It is essential that current leaderships in both countries find ways to peacefully manage old ambiguities and new problems in the future. This is their historical test. We need to rediscover the wisdom of President Carter and Vice-Premier Deng.