Dr. Alexander Bolton on the Intersection of Congressional Politics and China

On January 7th of this year, Congressman Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) was elected as the nation’s 55th House speaker in a historic post-midnight vote. McCarthy ascended to victory after a 5-day revolt from ultraconservative legislators and a bitter 15-ballot floor fight, which resulted in McCarthy making concessions. To make sense of the current state of the U.S. congressional politics and their implications for U.S.-China relations, I spoke with Dr. Alexander D. Bolton, an Associate Professor of Political Science at Emory University.

Dr. Bolton studies American political institutions with interests in how presidents, congresspeople, and other political agents maintain bureaucratic control and influence policymaking. His recent works include Checks in the Balance: Legislative Capacity and the Dynamics of Executive Power (Princeton University Press, 2021), “Gridlock, Bureaucratic Control, and Non-Statutory Policymaking in Congress” (American Journal of Political Science, 2022), and “Legislative Constraints, Ideological Conflict, and the Timing of Executive Unilateralism” (Legislative Studies Quarterly, 2022). He received his PhD in political science from Princeton University.

After the 2022 U.S. midterm elections, the Republicans have 222 seats in the House while the Democrats have 213. How narrow is the Republican House majority? How will this impact the Democratic Party’s legislative goals over the next two years?

Dr. Bolton: The Republican House majority is narrow, but narrow majorities in the House have become increasingly common over the last several decades. By way of comparison, in the 2020 elections, Democrats also won 222 seats.

These slim majorities pose challenges for party leaders, who must rely on commanding the floor with a majority if they want to pass their agendas. It also gives minority parties less incentives to cooperate on legislation, because if they believe they might be able to reclaim the majority in the next elections, they want to avoid giving legislative “wins” to the majority party.

This change in partisan control of the House will seriously stymie the legislative ambitions of the Democratic Party and the Biden administration. Any legislation will now need approval from Republicans in the House and the Senate to pass. In the last Congress, Democrats could use procedures like reconciliation to bypass Republicans in the Senate in order to enact bills like the Inflation Reduction Act. This option is off the table for passing party-line legislation now that Republicans control the agenda in the House of Representatives.

Republican Senator Kevin McCarthy secured his House speakership after 15 rounds of voting and a string of key concessions to far-right conservative lawmakers. Could you provide some insights into what went on behind the scenes in McCarthy’s speaker election?

Dr. Bolton: It has been a century since a candidate for Speaker has been unable to command a majority on the first ballot, so this was quite a remarkable event. The dynamics of this Speaker race reflected several fractures in the Republican caucus. Some members appeared to personally distrust Speaker McCarthy and were likely never to vote for him. Others, however, took advantage of the narrow Republican majority to extract concessions—that would advance their own political and policy causes—in exchange for their votes.

We don’t have a full public accounting yet of all the “deals” that were made behind closed doors for votes, but some have been publicly reported. The House Freedom Caucus, which is comprised of some of the most conservative members of the caucus, will now have greater representation on the House Rules Committee, where they can impact what bills and amendments are considered on the floor. Another key concession to the holdouts was to allow any Republican member to introduce a “motion to vacate the chair,” which could effectively depose Speaker McCarthy if a majority of the House agrees to the motion (which could occur with just a handful of Republican defections). Together, these types of concessions have the effect of empowering the holdout votes in the policy process moving forward and weakening Speaker McCarthy’s procedural control over the chamber.

Does the failure of House Republicans to unite around Kevin McCarthy for House Speaker foreshadow any specific difficulties Republicans will face in governing? What does this portend, in your view, about American democracy? Is this a post-Trump phenomenon?

Dr. Bolton: The election for Speaker highlighted some important features of the new Republican majority. First, the caucus is fractured, to some degree on ideological lines but also on how the House should be run. Speaker McCarthy had to made significant concessions to secure the holdouts’ votes, but in doing so he devolved a significant degree of power from the leadership to individual members.

Second, there is a small, but resolved, portion of the caucus that has demonstrated their willingness to obstruct until their demands are met. And the leadership has demonstrated the willingness to eventually meet those demands. I cannot help but think the speakership election demonstrated to those members the real power that a small group in a very narrow majority can have to bend policy in their direction. They will be tempted to use this power on all sorts of legislation, small and large, with potentially profound effects on issues like government funding and the debt ceiling. Moreover, their leverage has only increased with the set of procedural concessions made by Speaker McCarthy to win the position.

Of course, the right wing of the caucus is not the only set of members with this leverage. It will be interesting to see whether more moderate factions of the Republican caucus will use their votes to shape policies. They, for instance, can credibly threaten to team up with Democrats to use discharge petitions (which can bypass the Republican-run Rules Committee and bring bills to the floor if a majority of House members sign them) or vote down procedures for considering legislation if they feel it will shift policy in too extreme a direction.

Together this suggests that Speaker McCarthy will face a precarious balancing act in getting his caucus to advance legislation in a united way. On top of this, do not forget that he also needs to negotiate with Democrats in the Senate and President Biden to pass legislation that they can also agree to. This is a tall order for any legislative leader.

In terms of governance, all of this adds up to a recipe for gridlock on any issue that does not command wide bipartisan support. Unfortunately, on some of the major issues that the new Congress will confront (most notably, raising the debt ceiling and funding the government), the different factions of the Republican caucus and Democrats have staked out (at least as of now) wildly divergent positions. These will need to be reconciled to avert major policy and economic catastrophes. Whether McCarthy’s speakership can survive that negotiation remains to be seen.

I do not think this is a purely post-Trump phenomenon. Very recently, similar dynamics existed during the Obama administration when the Tea Party Republicans were a constant source of agita for Speaker John Boehner on similar issues (most notably spending and the debt ceiling). Throughout history, congressional majorities have often had deep ideological and governing divisions that had to be overcome to govern. However, adding on top of this, the combination of marginal majorities and cross-party ideological polarization that we have in the contemporary moment exacerbates these issues.

After securing his speakership, McCarthy conveyed his belief in proper checks and balances to hold the government accountable: “it’s time for [the House] to be a check and provide some balance to the president’s policies.” In your book Checks in the Balance: Legislative Capacity and the Dynamics of Executive Power with Sharece Thrower, you explored whether “checks and balances [are] enough to constrain ambitious executives.” What does a divided Congress—with a Republican House and a Democratic Senate—mean for President Biden’s executive agenda?

Dr. Bolton: The legislative gridlock he is likely to face will certainly make it tempting for President Biden to shift his focus toward using the executive branch to create policy wins that he can campaign on if he runs for reelection. This might take the form of executive orders or new regulatory policies. However, my research and others suggest that there are limits to how much can be achieved with such an approach.

In general, presidents and agencies are reluctant to push the bounds of their authority when they face opposition in Congress. Even though Republicans in the House cannot unilaterally pass legislation to overturn executive actions they oppose, new executive actions often require funding to implement, and in that context House Republicans will have significant leverage. Moreover, if President Biden or other executive actors go too far in the view of the new Republican majority, they possess a wide arsenal of tools to impose political costs on the administration. For instance, incoming Republican committee chairs can pursue aggressive and contentious oversight that can diminish the president’s standing in the eyes of the public and tie up agencies and officials in subpoenas, depositions, and public testimony. They can refuse to take up legislation that is important to President Biden’s agenda. In the extreme, they can impeach officials in the executive branch. Substantial numbers of Republicans have already called for the impeachment of Department of Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas. For these reasons, even though presidents and agencies have a lot of incentives to “go around” Congress and pursue unilateral policymaking when congressional majorities oppose them, they often in practice exercise considerable caution to avoid these types of sanctions and the possibility of “poisoning the well” for future cooperation with Congress they will need.

On top of congressional sanctions, President Biden and executive agencies will also need to consider whether their actions will stand up in the federal courts, which—after the Trump administration—have a distinctly conservative bent. Federal judges from the Supreme Court have not been reticent to nullify actions by the Biden administration and question the constitutional scope of administrative authority in contemporary politics. Thus, judicially-imposed limits on an aggressive unilateral policy also cannot be discounted.

At the moment, it appears that the polarized Congress can coalesce on one matter: China. Since early 2021, around 400 bills or resolutions concerning China have been put forward by American policymakers. In your view, how deep is the current bipartisan consensus on China? What should we expect from the new Congress on China policy?

Dr. Bolton: I think the statistics you cite suggest that members of Congress in both parties have concerns about China and US policy toward China. That manifests in a multitude of policy domains, including trade policy, intelligence, defense, economic security, human rights, technology policy, and more. It is clear from both the rhetoric and actions of the current Congress that members in both parties see competition with China as a key strategic challenge for the United States moving forward.

In the last Congress, several bills related to China passed by large margins. For example, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (P.L. 117-78) passed without opposition in the House or the Senate. The Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer Act of 2022 (P.L. 117-183), which has important provisions related to China, passed the House with 415 votes and unanimously in the Senate. This makes it clear that there are at least some areas of bipartisan consensus on China in the Congress.

In his first speech after being elected Speaker, Kevin McCarthy identified “the rise of the Chinese Communist party” as one of the two critical challenges facing the United States (along with the debt). Given this, it is safe to say that US-China relations will be a frequent topic of deliberation in the 118th Congress. How these concerns will translate into legislation and official policy changes remains to be seen.

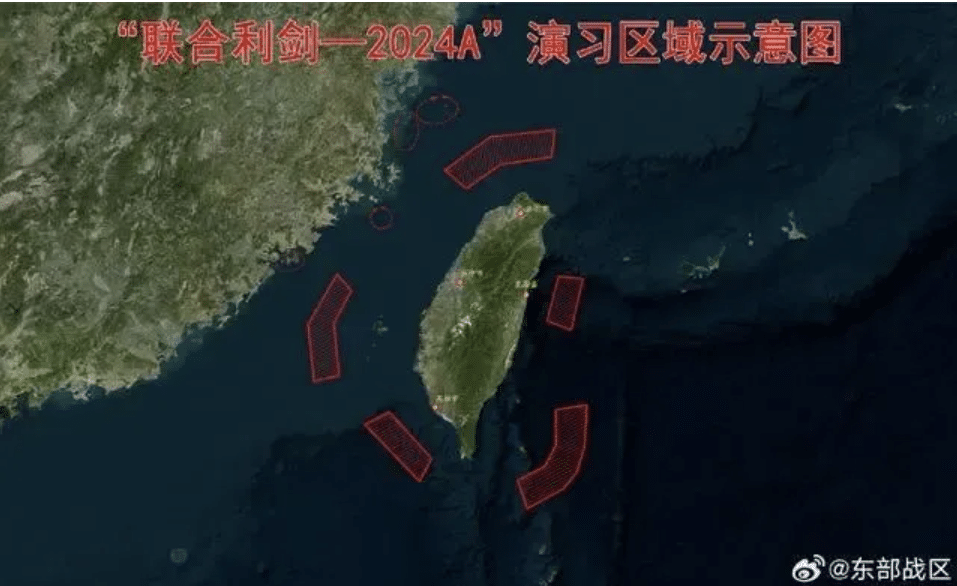

Specific issues that are likely to emerge include: lessening the reliance on Chinese production for vital aspects of the supply chain; the operation of apps with Chinese parent companies, such as TikTok, in the United States; human rights, particularly in the Xinjiang province and Tibet; US corporations’ willingness to comply with Chinese demands in order to operate in China; the origins and emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic; trade practices; Taiwan policy; Chinese influence in the South China Sea; and more.

On January 10th, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 365 to 65 in favor of creating the Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party, marking one of the first votes since the Republicans took control of the House. What is important to know about this committee on U.S.-China competition? Furthermore, Speaker McCarthy said in support of the resolution: “You have my word and my commitment. This is not a partisan committee. This will be a bipartisan committee.” Will this be the case?

Dr. Bolton: This vote is suggestive of the deep concerns across party lines about China policy. The committee will be chaired by Representative Mike Gallagher who, while very conservative and known for being a “hawk” on China issues, has not indicated that he intends to lead the panel in a particularly partisan direction. The committee does not have “legislative jurisdiction”; instead, its role is to investigate issues and report recommendations to the House of Representatives. The credibility of those recommendations and whether they are ultimately translated into policy changes that the Democratic-controlled Senate and President Biden can sign onto will depend in part on whether the committee does investigate and deliberate in a manner that brings Republicans and Democrats to some consensus.

Notably, some Democrats voting in favor of the committee did so with some reservations about the direction it will go. During the debate on the resolution to create it, Rep. McGovern said, “many of us have concerns about this turning into a committee that focuses on pushing Republican conspiracy theories and partisan talking points. We certainly don’t want it to turn into a place that perpetuates anti-Asian hate. We cannot and will not tolerate that.”

To me, all this indicates that there is an opportunity for bipartisanship on issues within the jurisdiction of the committee but there’s no guarantee that it will emerge. Whether the committee can leverage these opportunities to create meaningful policy changes will depend in no small part on the leadership of Rep. Gallagher and how he decides to set the agenda for the panel.

One central issue in U.S.-China relations is the congressional position on Taiwan. McCarthy supported Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and voiced his desire to do the same as Speaker of the House. In your estimation, what is the likelihood of McCarthy paying a visit to Taiwan?

Dr. Bolton: At this point, it is almost certain that Speaker McCarthy will visit Taiwan. He supported Speaker Pelosi’s trip last year, and all reporting suggests he intends to go himself in the relatively near future.