Donald Trump Reveals His Isolationist Foreign-Policy Instincts

Conventional candidates for the American presidency signal how they might deal with the world in three main ways. First, they are expected to issue detailed foreign policies, though—in truth—few of these plans are robust enough to survive a brush with actual events. Next, by choosing advisers known for strong views or special expertise, candidates nod to their own priorities. The third signalling mechanism is the most nebulous but the most useful, and happens when contenders let slip some remark that betrays their deepest prejudices and gut instincts.

To date Donald Trump, an unconventional candidate, has come a long way without revealing very much at all about his worldview. He has offered such bumper sticker slogans as “Bomb the shit out of ISIS”, and dodged questions about his preferred sources of geopolitical advice, recently declaring: “I’m speaking with myself, number one, because I have a very good brain.”

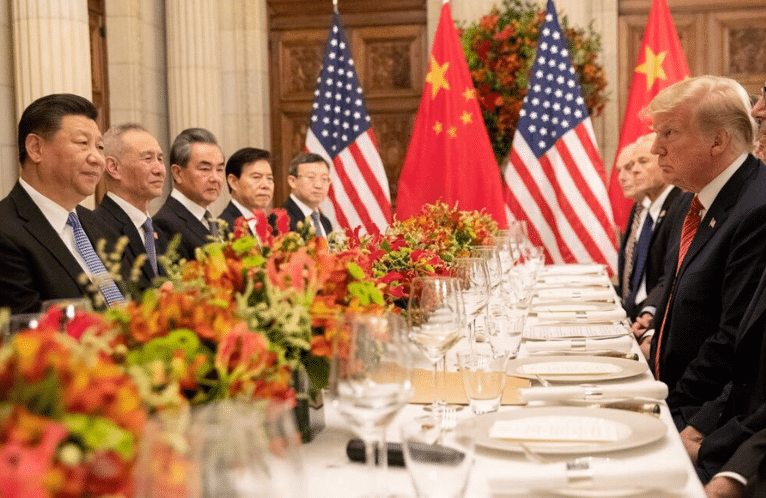

On March 21st, however, the real estate tycoon and Republican presidential frontrunner visited Washington, DC for a day of traditional foreign policy chin-stroking and speechifying. While in the capital Mr Trump joined presidential rivals in addressing some 18,000 supporters of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), an influential pro-Israel lobby group, outlining his most detailed thoughts yet on the prospects for Middle East peace, on curbing Iran’s nuclear ambitions and on defeating the violent extremists of the Islamic State. In an earlier meeting at the Washington Post newspaper, the businessman revealed the names of five close foreign policy advisers.

These set-piece encounters revealed little. Mr Trump’s AIPAC speech, which unusually for him he read from a prepared text, was a mixture of pandering, implausible bluster and contradictory promises. The billionaire denounced the United Nations as an anti-Israeli opponent of democracy. “We will totally dismantle Iran’s global terror network, which is big and powerful—but not powerful like us,” he promised, without further explanation. He said he would “dismantle the disastrous deal” struck by President Barack Obama to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions, then seemed to say that he would enforce it, or perhaps the sanctions regime that preceded it, “like you’ve never seen a contract enforced before, folks, believe me.”

In recent months Mr Trump has set nerves jangling among conservative supporters of Israel by suggesting he would be “neutral” in efforts to broker peace between Israel and the Palestinians. In his speech to AIPAC the businessman worked hard to cast himself as sternly pro-Israeli. He variously cited his role as Grand Marshal of the 2004 “Salute to Israel” Parade in New York City and his daughter’s conversion to Judaism after marriage. Months after angering a gathering of Jewish Republicans by fudging his views on the status of Jerusalem, Mr Trump bowed to conservative pressure and pledged to AIPAC that he would move the American embassy to that divided city, calling it “the eternal capital of the Jewish people”.

That did not shield him from criticism. Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, a doctrinaire Republican who is Mr Trump’s closest rival in the presidential contest, scolded Mr Trump for using the word “Palestine” to describe the Palestinian homeland, saying that “Palestine has not existed since 1948”—a position calculated to appeal to delegates at AIPAC.

The little-known advisers named by Mr Trump shed only limited light on his views. They include Joseph Schmitz, a Pentagon Inspector General under George W. Bush; to Walid Phares, a Lebanese Christian academic who has in the past advised warlords in Lebanon; J. Keith Kellogg Jr., a retired army Lieutenant General and former chief operating officer for the Coalition Provisional Authority in Baghdad; and Carter Page, a businessman and analyst specialising in the oil and gas industry in the former Soviet block.

Where Mr Trump was more revealing was in comments and asides that pointed to his deep instincts on foreign policy—instincts which often mark a sharp break with recent Republican orthodoxy.

Most straightforwardly, Mr Trump brought his constant campaign-trail refrain about being a savvy businessman and deal-maker to AIPAC, offering America as a broker between Israel and the Palestinians. “Deals are made when parties come together, they come to a table and they negotiate. Each side must give up something,” he told delegates.

In the poisonously divided politics of 2016 Washington, even suggesting that Israel might have to give anything up in the name of peace involves challenging conservative shibboleths. In recent years, Republicans have aligned themselves with the views of Binyamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, in suggesting that Israel should not be prodded to engage in talks, because the Palestinian side has shown no sincerity or seriousness as a potential partner for peace.

Without endorsing that bleak view the Democratic front-runner, Hillary Clinton, used her own speech to AIPAC to hint, subtly, that a President Trump might prove to be an alarming partner for Israel, thanks to his zeal for deal-making. Without naming Mr Trump, the former first lady, senator and secretary of state told AIPAC delegates: “We need steady hands, not a president who says he’s neutral on Monday, pro-Israel on Tuesday and who-knows-what on Wednesday because everything’s negotiable.” Mrs Clinton also suggested that Mr Trump’s proposed ban on Muslim travel to America and anti-immigrant rhetoric were reminiscent of the dark days in the late 1930s when America refused entry to Jewish refuges from Europe.

More broadly, Mr Trump seems ready to break with Republican traditions of using America’s wealth, diplomatic clout and military muscle to promote universal values of economic and political freedom around the world—traditions which have dominated the party since the days of Ronald Reagan and the Cold War.

Appealing to Americans who want to feel safe from Islamic extremism but who wonder what almost 15 years of intervention in the Muslim world has achieved, Mr Trump has spent months promoting an America-First policy of unleashing no-holds-barred violence, including torture, against foes in the Middle East, while shunning anything that smacks of nation-building far from home.

While doing the rounds in Washington, Mr Trump expanded a little more than before on those views. Asked about the future of NATO at the Washington Post, the businessman scolded other members of that Atlantic alliance for doing too little after Russia invaded Ukraine on their doorsteps. “Why are we always the one that’s leading, potentially the third world war, okay, with Russia?” he asked. To the cable television news station CNN, Mr Trump said that while he would remain a member of NATO he would “certainly decrease” American funding for the alliance.

Asked about how to counter Chinese aggression in the South China Sea and Asia by theWashington Post, Mr Trump again voiced longstanding gripes about how such allies as Japan and South Korea only pay for some of the costs of American bases in the region. Does America gain anything by having bases overseas, he was asked? “Personally I don’t think so,” Mr Trump replied.

These expressions of pull-up-the-drawbridge truculence are far from the sort of polished policy papers and working-group reports that other campaigns like to produce. But Mr Trump keeps saying things like this—at some point it seems reasonable to believe that these remarks reflect his views. What is more, his supporters love this message of chin-jutting, heavily armed isolationism. If elected, President Trump will be able to claim a mandate for ending decades of global power projection. It may be frustratingly hard to pin the Republican front-runner down on how, precisely, he would deal with the world. But do not discount the possibility that he intends to deal with it as little as he can.

Mar. 22, 2016 on Foreign Affairs

Read more here