Exclusive: Will Australia’s Defense Spike Threaten Chinese Energy Security?

On Thursday, February 25, Australia released its 2016 Defense White Paper indicating a massive rise in defense spending of over 81% over the next ten years, 25 percent of which would be specifically invested in what the paper describes as “the most comprehensive regeneration of our Navy since the Second World War.”

The investment would be the largest ever defense procurement, with the largest part of the investment replacing Australia’s current diesel and electric-powered Collins Class submarines with new submarines.

The budget spike comes at a critical time as tensions have risen in the South China Sea due to a US Navy destroyer that sailed within 12 nautical miles of a contested island meant to “counter efforts to limit freedom of navigation” in the contested area.

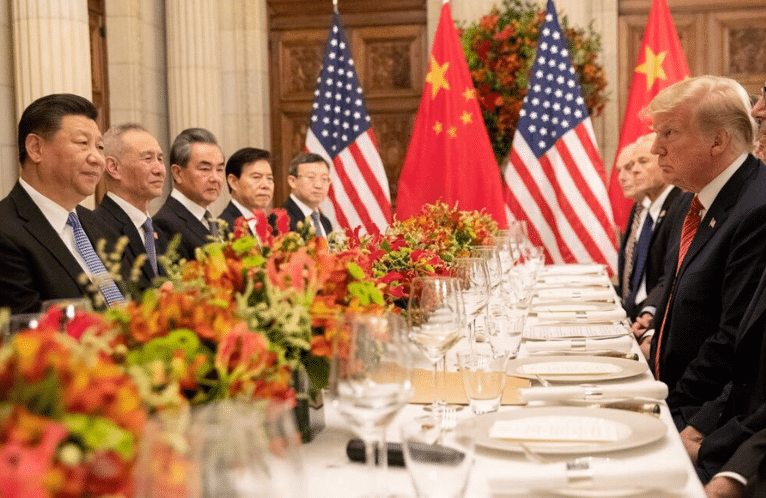

According to the white paper, the raised spending, which will comprise of 2% of Australian GDP in 2021, was influenced by several factors, including the evolving relationship between the United States and China, territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas, crisis on the Korean Peninsula, and the growing danger of terrorism, particularly the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or Daesh).

Australia has objected to Chinese efforts reclaiming land in the South China Sea, and has encouraged a code of conduct between ASEAN and China in the contested waters. Furthermore, a recent statement made by US Navy Vice Admiral Joseph Aucoin stating that Australian operations to protect the “freedom of navigation” in the South China Sea would be “valuable” has unsurprisingly aggravated China[6]

Hua Chunying, a Chinese Foreign Minister Spokeswoman, was bothered by Australia’s statements on the South China Sea. “It mentions Australia is willing to enhance cooperation with China, China welcomes that and hopes it can translate these positive statements into concrete actions,” Ms. Hua said, “We also noticed that this white paper made some remarks about South China Sea and East China Sea. These remarks are negative and we are dissatisfied about this.”

A growing Australian defense would be troubling for China. In the White Paper, Australia reiterated its close ties to the United States while also acknowledging its strong relationship with China. However, a more diverse Australian Navy would still be an important factor for China, particularly for Chinese energy security.

Malcolm Davis called China’s energy sector the life-blood of its economy and projects that by 2020, imported oil would make up 66% of total oil demand. Another important aspect of Chinese energy security is the maritime lines of communication. With 80% of China’s energy coming through the Malacca Strait, it is important for China to secure the line of communication through the straits of Indonesia, which connects Chinese energy supply, and trade, with the Middle East and Africa.

In November 2003, Chinese President Hu Jintao recognized the Malacca Dilemma, saying that “certain powers have all along encroached on and tried to control navigation through the [Malacca] Strait.” The Malacca Strait, which connects the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea, is bordered by Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore. Singapore may be the most significant, as a hypothetical blocking of the Strait would cripple China’s energy and trade line with the Middle East, Africa, and Europe.

Some alternatives to the Malacca Straits are the Lombok-Makassar Straits, which also connect the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean. These straits are deeper and currently used to allow the passage of supertankers, which otherwise could not sail through the Malacca Strait. However, while the Malacca Strait empties near the Bay of Bengal, which would give China closer access to “strategic enclaves” in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, it focuses on the hotly debated “string of pearls”. On the other hand, the Lombok-Makassar Straits empty near the Timor Sea, only some 1700 kilometers Darwin, Australia, which hosts a military base.

Should a situation ever arise where the Malacca Strait is closed off, China would instead be reliant on the Lombok-Makassar Straits for trade and energy. However, the Lombok-Makassar Straits would make China particularly vulnerable to Australia, which would be particularly dexterous in the open waters of the Indian Ocean near the Straits. If it ever comes to a point where both straits are closed off, Chinese lines of communication would be drastically affected, hurting the much needed communications with Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. While the Belt and Road initiative, deliberations with Burma, and the Northern Route could provide China with alternatives to the Straits, such ambitious alternatives are not completely feasible at present to support the Chinese economy in its present form.

In 2008, former Australian prime minister and China admirer Kevin Rudd feared that the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QSD), defense coordination between Australia, India, Japan, the United States advocated by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007, seemed too much like a containment policy on China. Tony Abbott was a vocal critic of Rudd’s withdrawal and, after succeeding Rudd as Prime Minister, sought closer defense relations with Japan and India. Some scholars believe current Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has a much more nuanced view of the world and hopes to seek good relations with both Beijing and Washington.

After Rudd’s decision to pull out of the QSD, it seemed that Abe’s brainchild was gone and forgotten. However, with the Japanese redefinition of its constitution, closer security ties between India, Japan, and the United States, combined with Australia’s growing defense budget and common defense interests in Asia, one wonders whether the QSD has ever left at all.

By AARON WALAYAT Feb. 29, 2016 on USCNPM