Japan’s Prime Minister Takaichi Finally Says Something Close to What Beijing Wants to Hear

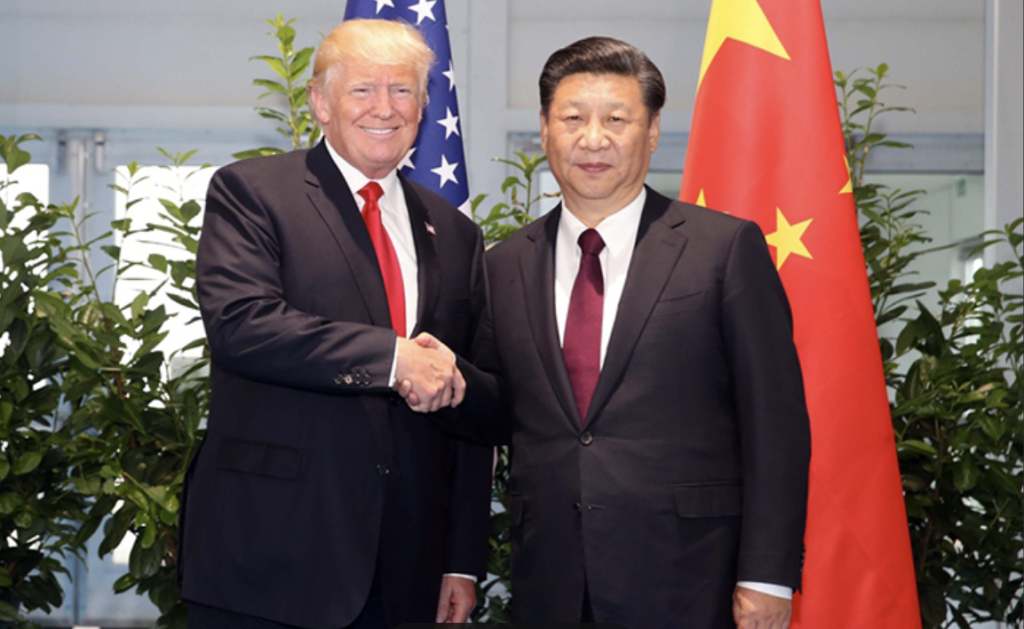

Managing Rivalry: China’s Strategy for Coexistence with the U.S.

Source: Fudan University

Over the past three centuries, the global economy has witnessed the rise of three “world factories”: Britain in the 19th century, the United States in the 20th century, and China in the 21st century. While Germany and Japan also developed formidable manufacturing capacities, structural constraints prevented them from attaining the status of a true “world factory.” In 2010, China surpassed the United States to become the world’s largest manufacturing power, and over the following 15 years, it continued to widen its lead. This development represents one of the most consequential geopolitical shifts of the first half of the 21st century.

This transformation has generated four profound repercussions for the United States.

First, the erosion of U.S. manufacturing has fundamentally disrupted its industrial ecosystem, thereby constraining its capacity for innovation. Innovation does not emerge solely within laboratories; it requires extensive application scenarios to bridge the so-called “valley of death” between technology and commercialization. The strategy of offshoring low-end production while retaining only high-end segments is ultimately unsustainable. Much like a forest cannot nurture towering trees without the presence of shrubs and undergrowth, a robust industrial base requires both low-end and high-end production.

Second, the decline of manufacturing has weakened the United States’ defense industrial base. During the Russia–Ukraine conflict over the past three years, although Russia’s battlefield performance has been uneven, the United States has also faced significant challenges in sustaining a prolonged war of attrition. This constraint helps explain President Trump’s eagerness to bring the conflict to a close.

Third, the weakening of manufacturing has severely eroded the U.S. fiscal foundation. Today, federal debt resembles a vast barrier lake that can only be tenuously supported by the “predatory” financing capacity enabled through dollar hegemony. In the longer term, however, this reliance is akin to “drinking poison to quench thirst,” and cannot be sustained indefinitely.

Fourth, the decline of manufacturing has expanded the geographic scope of the Rust Belt and accelerated the erosion of a middle-class-centered social structure. A strong middle class has long functioned as the stabilizer of American democracy. Its weakening has therefore had a direct impact on the resilience and quality of U.S. democratic governance.

Jake Sullivan, one of the leading strategists of a new generation in the United States, has characterized U.S.–China industrial competition as a process of “hollowing out.” To confront this challenge, he introduced the notion of a “New Washington Consensus,” urging the U.S. to mobilize state power—rather than relying primarily on global markets—in order to revive domestic manufacturing, rebuild the industrial ecosystem, and restore national competitiveness. Over the course of three administrations—Obama, Trump, and Biden—this mobilization has gradually taken shape, yielding a bipartisan consensus and a systematic strategic framework for industrial revitalization. This stands today as one of Washington’s most consistent and enduring grand strategies.

Since March 2018, the U.S. economic offensive against China has escalated steadily. This contest between the world’s two largest economies is fundamentally about the status of “the world’s factory” and, by extension, the survival of U.S. hegemony. Washington has deployed tariffs to constrict market access for Chinese goods, with average tariff levels now exceeding 50 percent. In August alone, China’s exports to the U.S. declined by 33 percent year-on-year. At the same time, Washington has turned to technological restrictions to impede China’s industrial upgrading: the shortfall in deliveries of China’s C919 aircraft this year offers one visible example, while the semiconductor sector faces even sharper headwinds. In addition, financial instruments have been leveraged to weaken Chinese firms’ access to capital. In artificial intelligence, for instance, China’s total financing volume amounts to only one-tenth that of the United States.

China’s ascent as a manufacturing power was enabled by globalization, which provided critical resources in markets, technology, and finance. The current U.S. strategy seeks to dismantle precisely this form of globalization—one that had been particularly favorable to China’s rise.

Against this backdrop, the only viable response for China is to expand openness. Washington’s objective is to reduce China to a closed, self-sufficient economy dependent on “internal circulation,” thereby raising the structural costs of its development. Beijing, however, must act in the opposite direction. Historical precedents underscore this logic: Britain’s repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 and its embrace of free trade heralded the height of the British Empire, symbolized by the 1851 Great Exhibition in London; the United States’ Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, championed by Secretary of State Cordell Hull, helped underpin its eventual global leadership after World War II.

In recent months, however, the U.S. has secured trade agreements with the EU, the UK, Japan, South Korea, and others, institutionalizing retaliatory tariffs of 10 and 15 percent. These moves have effectively rolled back decades of hard-won liberalization under the postwar trading system, pushing international trade “back to square one.”

For China, as the world’s second-largest economy and its largest exporter, the strategic imperative is to move counter to this trend. Accelerating free trade negotiations with key partners to push for lower tariffs—and even pursuing bold unilateral liberalization measures, such as recent visa-free entry policies—would ensure that U.S. protectionism ultimately isolates Washington rather than Beijing. In doing so, China could assume a leadership role in shaping the next phase of globalization and global governance.

(On September 27, Fudan University’s Center for American Studies marked its 40th anniversary. At the conference, Professor Li Wei, Vice Dean of the School of International Studies at Renmin University of China, delivered a keynote speech entitled “Industry and Hegemony.” The above reflects a summary of his remarks, compiled by Peking University’s Institute for Global Cooperation and Understanding and subsequently edited by The US-China Perception Monitor. Its original title was How Should China Respond to U.S. Containment? )

Author

-

Li Wei is a professor and vice dean of the School of International Studies at Renmin University of China