Winners Can’t Take All in AI

- Analysis

Meicen Sun

Meicen Sun- 07/08/2025

- 0

The CEO of the world’s leading AI chipmaker Nvidia recently declared U.S. chip export controls a “failure” in a speech at a tech show in Taiwan. Rather than curbing China’s AI development, Jensen Huang notes the tariffs and regulation attempts have spurred it.

Lauded as a prototype of innovation under constraints, China’s AI model DeepSeek stunned the world earlier this year. The U.S.-enforced shortage of frontline chips had reportedly driven Chinese developers toward compute-efficient alternatives which, ironically, sent the stocks of the U.S. chipmakers into a temporary crash this past winter.

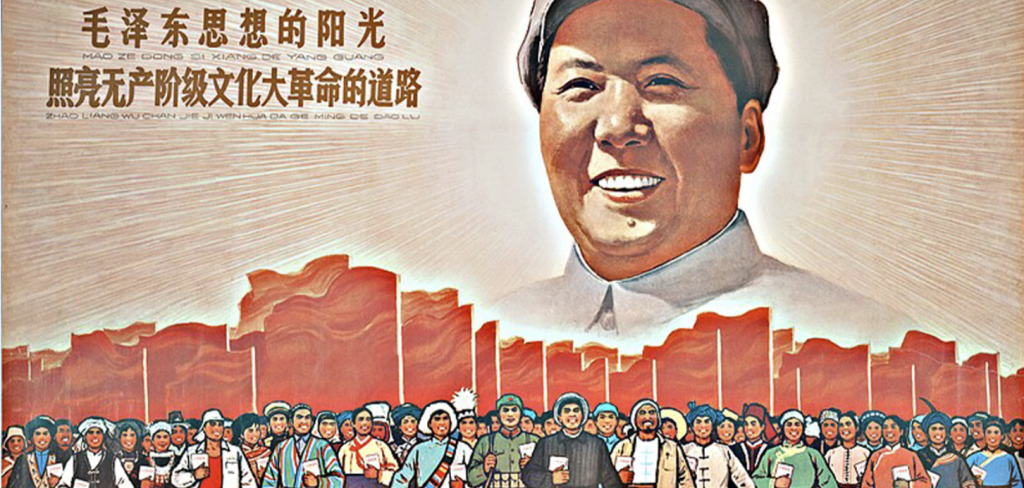

But this isn’t the failure of one export control measure or another. It’s the failure of the winner-take-all logic that underlies both export controls and immigration restrictions — such as the one targeting Chinese students announced in May. The trigger-happy reflex has not only been the leitmotif of U.S. technology policy. It has been the drumbeat to U.S. politics at home and abroad.

The winner-take-all mindset has historically served certain segments of the hierarchy in the U.S. all too well, while damning others. It has inspired heroic acts in wartime of all shapes and forms – pandemics, terrorist attacks, and even natural disasters as has been noted.

No matter the arena, it’s about othering the opponent as an existential threat – a virus, a person, a nation. It’s “us” versus “it.” Not that it must be anything grand; televised “Sunday Night Football” for instance perhaps would be a lot less fun without sudden-death rules created just to ensure only one team prevails.

A winner-take-all approach to AI is, quite plainly, unhumanitarian. Contrary to skeptical views, generative AI already seems to have improved learning outcomes. Still, these are dwarfed by the vastly untapped potential of AI in improving health outcomes.

From drug development to cancer diagnosis and treatment, AI’s promise is as material as it is measurable. For example, AI catches 64% of lesions previously missed by radiologists and detects breast cancer four to six years earlier than conventional methods.

Those awaiting a lifesaving cure would be less concerned about its national origin than whether it delivers or not. Playing to “win” a simulated wargame by withholding resources crucial to AI development and deployment that could benefit billions living and breathing is logically flimsy and morally bankrupt.

And even if the U.S. still wants to give winner-take-all a shot, it simply can’t. Unlike nuclear weapons borne out of the closely guarded Manhattan Project in the mid-20th century, AI has evolved out of a densely enmeshed global network of scientists over decades.

In this regard, AI exemplifies how science has always been done: Teams produce more and better research than individuals, especially international teams. During my time at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, I worked on a cryptography project for hazardous DNA screening led by scientists from the United States and China – research with direct implications for combating bioweapons. The complexity of modern national security threats defies the attempt to tackle them by any single nation, no matter how technologically advanced.

Most notably, while the United States and China are each the frontrunners in AI, they fare better when working together. A study tracking 350,000 scientists and five million papers in AI discovers that when co-authoring with those from the other side of the Pacific, both the United States and China see a significant boost in research impact, and increasingly so. Key to this synergy is the dynamic migration between the two countries, such as when U.S.-educated Chinese scientists continue to work with their former American colleagues and mentors when they return home.

AI is, again, the latest example of a “collaboration premium” for U.S. and Chinese scientists with enormous spillover benefits to the global society at large. This premium means that a winner-take-all strategy is inherently self-defeating, for trying to get a bigger slice of the pie will drastically shrink the pie itself.

Given the pace at which AI is moving, what looks like a big slice today may just look a whole lot smaller tomorrow.

Celebrated for its foresight into the information age, Vannevar Bush, the late engineer who supported the Manhattan Project as leader of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development, wrote in a July, 1945 essay in The Atlantic that at its core was a manifesto of science for humanity.

The end of World War II threw scores of American scientists dedicated to wartime projects into an existential crisis. Bush, along with others, steered the U.S. science and technology engine out of an imminent stall and into a sustained momentum through such pivotal policy levers as the National Science Foundation. Recent cuts at the NSF by the White House as a result of the Department of Government Efficiency that eliminated funding for nearly 400 grants has brought research to a near standstill.

The acute panic about DeepSeek may have eased. The erasure of federal funding for research signals, however, that the chronic disregard for science endemic to this country has metastasized, and nothing feeds it more than a delusion to “win it all.”

Today, instead of merely sending both sides to the brink of conflict, a relapse into a zero-sum compulsion by the United States or China will doom the whole of humanity from exploring AI’s benefits while averting its risks.

The country is again at a crossroads. Indebted to those who brought us here eight decades ago, we owe it to future generations to continue on the path of technology-enabled possibilities — a path no one of us can, or should, walk alone.

Meicen Sun is an assistant professor at the University of Illinois School of Information Sciences and an affiliated faculty at MIT FutureTech. She is a Public Voices Fellow with The OpEd Project.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.