Strategic Calculations: China’s Dilemma Between Trump and Harris

- Analysis

Jinghao Zhou

Jinghao Zhou- 09/10/2024

- 0

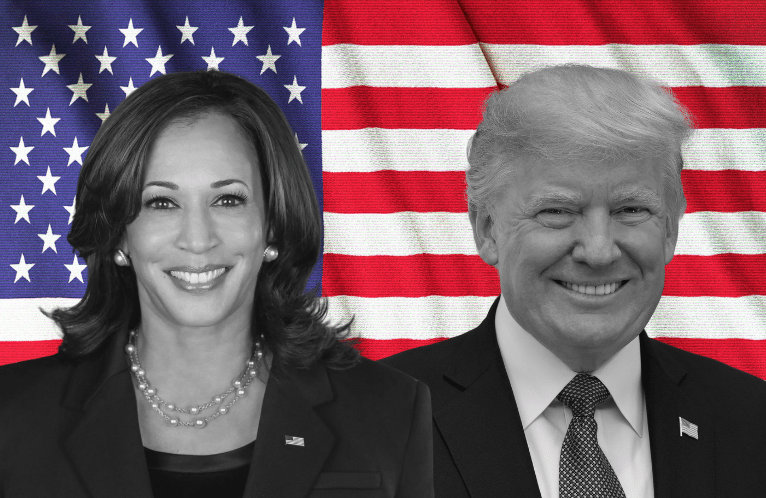

On January 20, 2024, the United States will have a new president—either Kamala Harris or Donald Trump. As the chief architect and representative of the nation on the global stage, the new president will significantly influence the direction of the already fragile U.S.-China relations.

Chinese and American scholars see little difference between the two candidates’ potential policies towards China and agree that U.S.-China relations are unlikely to improve under either Trump or Harris as they are two “bowls of poisons.” While China is grappling with conflicting views and finds it challenging to decide which candidate to support, it still prefers a candidate who aligns more favorably with its current situation.

Harris is unlikely to formulate a brand-new foreign policy toward China in a short period and her economic plan is largely an extension of Biden’s existing policies. If elected, she will likely follow the Biden-Obama foreign policy, which would make her approach more predictable for China. On the other hand, China understands Trump’s unpredictability and aggressive tactics toward China could precipitate escalated tensions. If Trump returns to the White House, China will need to adapt to Trump’s second-term policy to manage its relations with the United States.

Principles of Trump’s Foreign Policy

While adjusting his emphasis and strategy of implementation, the principles of Trump’s foreign policy will continue to blend realist and nationalist tendencies, including his core doctrine of “America First.” His decisions will be based on real-world outcomes rather than rigid ideology. The Biden/Harris administration places more emphasis on human rights and democracy. Harris’s campaign slogan centers on defending American democracy, portraying Trump as a significant threat to it. Biden has publicly referred to Xi Jinping as a dictator multiple times, and in 2021, he hosted the Summit for Democracy, which saw participation from over 100 world leaders, including representatives from Taiwan.

When Trump met Xi Jinping in Beijing in 2017, he did not mention China’s human rights issues, despite demands from U.S. human rights organizations. Trump continues to emphasize his friendship with Xi, praising him as smart, talented, and capable of governing China, a country of 1.4 billion people.

During his presidency, Trump sought to ban TikTok, citing national security concerns. Now, he advocates for the app, attracting nearly 10 million followers. This shift is a strategic move to appeal to younger voters and align with the interests of influential donors opposed to the ban. This reflects how Trump can trade principles for interests.

China, as an ideologically driven country, upholds Marxism and Communism as the foundation of its political power. Its foreign policy priority is to protect the security of the CCP regime. In this context, Trump’s realist foreign policy, which tends to prioritize practical considerations over ideological ones, may be seen as more advantageous for China.

Priority of Trump’s Foreign Policy

Trump’s foreign policy is often interest-driven and sometimes labeled as transactional diplomacy. During his first term, he pushed NATO allies to increase defense spending to reduce the financial burden on the United States and renegotiated NAFTA, resulting in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which boosted growth and employment in the U.S. manufacturing sector and safeguarded American workers’ interests.

Trump’s foreign policy will likely continue to be grounded in transactional interests. He will employ economic tools, such as tariffs and sanctions, to achieve his diplomatic objectives. If he were to increase tariffs on China to 60%, it could reduce China’s GDP growth rate by approximately 2.5% over the subsequent 12 months. Trump is not particularly supportive of green industries and may prioritize expanding oil and gas production, especially by aggressively exploiting shale oil. This could lead to lower oil prices, which in turn could hinder China’s electric vehicle industry.

He even wants to gain more benefits from Taiwan by balancing the trilateral relationship between the United States, China, and Taiwan. Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing almost 100%” of the U.S. chip business, arguing that the United States should not have allowed this to happen. If he is re-elected, Taiwan should pay more for protection. Much like Trump’s disparaging comments about NATO unsettled America’s allies, his remarks on Taiwan have sparked concerns about how a second Trump presidency might impact U.S. investments in Taiwan’s defense and how the United States would defend Taiwan under the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979. In contrast, Harris won’t abandon Taiwan. That is one of the most important reasons why China prefers Trump.

Transactional diplomacy lacks a long-term vision and can alienate allies and disrupt global cooperation because his approach primarily benefits the United States, so that U.S. allies may feel uncertain about America’s commitment to their security and interests. Conversely, China could exploit the United States’ transactional approach to negotiate more favorable terms in various agreements and take advantage of rifts between the United States and its allies to strengthen its geopolitical influence, fulfilling its central goal of the China Dream— the goal of the great renewal of the Chinese nation—and ultimately replacing America’s global leadership position.

Strategy of Trump’s Foreign Policy

Trump implemented a “maximum pressure” diplomacy strategy to maximize U.S. interests. During his first term, the Trump administration imposed enhanced sanctions on Iran after withdrawing from the Iran Nuclear Agreement (JCPOA), hoping to force Iran to negotiate not only its nuclear program but also its support for terrorism and missile programs. He applied maximum pressure to push North Korea to denuclearize and come to the negotiating table, imposed on Venezuela to pressure the Nicolás Maduro regime to step down and support opposition leader Juan Guaidó, and ordered airstrikes on Syrian government military facilities in response to allegations that the Assad regime used chemical weapons against civilians. Meanwhile, Trump also applied maximum pressure on U.S. allies, which strained relationships with many leaders from democratic countries and complicated efforts to build a strong and united front with global allies.

Trump has already strained relations with some countries. He threatens to halt military aid to Ukraine and allow Russia to “do whatever the hell they want to” to NATO countries if they do not increase their military budgets. Trump himself may not fear isolation, yet the isolated United States would suffer damage to its interests and weakened power to compete with China. This division is advantageous for China, as fragmented alliances weaken American international leadership and allow China to challenge the United States by exploiting its weakened position, further expanding its influence in Latin America, and leveraging European countries for its interests.

Trump has repeatedly stated that he would not hesitate to take tougher measures if China fails to comply with trade agreements. While Trump’s rhetoric may show a tough stance, actual foreign policy operations are often more complex and multifaceted than his rhetoric implies.

Historically, his maximum-pressure diplomacy has failed with China because it tends to invite defiance rather than compliance. Such an approach can be perceived as a challenge to national sovereignty, leading to a stronger backlash from Beijing. Maximum pressure diplomacy is less effective against China due to its economic strength, extensive global trade networks, and centralized political system, which provide resilience against sanctions and diplomatic isolation. China’s capacity for strategic retaliation often deters aggressive diplomatic tactics. Thus, China has experience in countering Trump’s maximum pressure diplomacy.

Trump’s Personality Diplomacy

Largely shaped by Trump’s personality, his diplomacy was characterized as vanity diplomacy or “bluster diplomacy.” This style focuses more on personal pride, image, and potential political gain than on substantive international relations, often at the expense of traditional diplomatic norms. Trump claims that Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin are his friends and that Kim Jong Un likes him a lot; he even said, “Kim Jong Un and I fell in love.” Trump frequently used superlatives to describe his achievements, often claiming to have accomplished more than his predecessors. He said he is the greatest president in history and the “best president of Israel,” aiming to bolster his legacy.

Recently, Trump stated that if re-elected, he would revoke China’s most favored nation status, and if Beijing were to attack Taiwan by force, he would retaliate by bombing Beijing. He has made repeated claims that he could end the war between Ukraine and Russia within a single day. This kind of rhetoric-driven diplomacy is low-cost, requiring no actual deployment of U.S. strategic resources while allowing him to pursue personal and national interests.

Unavoidably, Trump’s foreign policy style could create unpredictability and unilateralism. During his first term, he suddenly withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and Paris Climate Accord, recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, and moved the U.S. Embassy there. Trump’s unpredictability in a second term could be driven by a desire for retaliation. He blames China, at least in part, for his defeat in the 2020 election due to the COVID-19 pandemic. If re-elected, Trump would possibly retaliate against China. He has indicated that he would impose even harsher sanctions on Chinese trade and investigate the origins of COVID-19.

Trump’s unpredictable and unilateral foreign policy could strain alliances. China is pleased to observe a divided and turbulent world for two main reasons: First, China aims to expand its influence in international relations by advocating for a multipolar world order. Second, China may attempt to unify Taiwan by force while the United States faces massive conflicts and two or more full-up battle fronts. This is why Xi Jinping told Putin, “Right now there are changes – the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years – and we are the ones driving these changes together,” when he met Putin in 2023.

Conclusion

China understands the Chinese idiom “鱼和熊掌不能兼得” (Yú hé xióng zhǎng bùnéng jiān dé), which translates to “you can’t have both fish and bear’s paw,” meaning that you can’t have everything you want at the same time. If China prioritizes the political security of the Chinese Communist Party in its foreign policy, Trump’s approach might inadvertently support China’s objectives. Conversely, if China focuses on economic development, Harris would be the more favorable option. Should China seek to balance political security with economic growth, it is likely to lean towards Harris, as historical experience suggests that China might be willing to sacrifice some economic interests for political security. That said, if Xi Jinping continues to firmly uphold his political agenda centered on the party’s rule, China’s approach to the United States will likely tilt in favor of Trump. China would prefer to endure economic losses for the sake of political security under Trump rather than compromise its political security for economic gains under Harris. If Xi Jinping is willing to slightly modify its political agenda according to China’s current economic situation, China will choose Harris. Although Chinese state and social media have erupted with reports and posts critical of Kamala Harris, painting her as weak, and predicting that Donald Trump will return to the White House, China is preparing two scripts to play in dealing with China-U.S. relations in the next year.

Dr. Jinghao Zhou is an associate professor of Asian studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in New York. His research focuses on contemporary China, and U.S.- China relations. He has published six books and six dozen articles. His latest book is Great Power Competition as the New Normal of China-U.S. Relations (2023).

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.