China’s Retaliatory Sanctions Strategy

- Analysis

Kay Zou

Kay Zou  Jiachen Shi

Jiachen Shi- 07/10/2024

- 0

Since Xi Jinping’s rise to power, China’s wolf warrior diplomacy has been accompanied by a series of retaliatory sanctions against Western corporations and individuals. While politically motivated, China’s sanction strategy is largely reactive to Western sanctions, and thus often ineffectual. This reactive approach is in contradiction to the assertiveness associated with China’s recent diplomatic strategies and highlights a lack of cohesion in China’s posture toward what it views as its adversaries in the West. It is, therefore, worth examining the history and legal framework of China’s sanctions against the West and how these reflect China’s reactive attitude toward the United States and the European Union.

Evolution of China’s Sanctions Against the West

Prior to Xi Jinping’s ascendance to power in 2012, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) already employed sanctions against foreign countries. This policy, known as coercive diplomacy, includes popular boycotts, administrative discrimination, trade and investment restrictions, and limitations on tourism. An example took place in 2010, when China cut off imports of Norwegian salmon after the Nobel Committee awarded dissident Liu Xiaobo the Nobel Peace Prize. Although China still uses coercive diplomacy when dealing with other countries, this policy has drawbacks. Chiefly, coercive diplomacy is often enacted through extralegal means, which are informal and unsystematic. Moreover, China has mainly used coercive economic tactics against small, democratic countries which are American allies, rather than the United States itself. Thus, the Chinese foreign policy apparatus saw the need to develop a more standardized framework to enact sanctions against Western, and especially American, entities.

After 2012, the PRC began to explore methods to innovate its economic and political sanctioning. China participated in regulating sanctions in the UN Security Council (UNSC), mainly through voting on sanctions proposed to the UNSC. In 2014, China voted in favor of a UNSC resolution that enforced travel bans, asset freezes, and an arms embargo against “people who threaten peace and stability in Yemen.” While China supported similar sanctions, it also frequently opposed UNSC sanctions against its allies, including North Korea, Iran, Syria, and Russia. China currently continues to protest UN sanctions against its allies. In May 2024, for instance, China resisted “blindly imposing sanctions” on North Korea, after abstaining during a UNSC vote which sought to renew UN scrutiny on North Korea.

Despite only recently entering the unilateral sanction game, China has quickly created a robust legal framework to impose sanctions. The development of this series of rules and laws surrounding sanctions accelerated in 2018, spurred by the trade war initiated by the Trump administration. Still, trade and economic factors only partially determined the nature of Chinese sanctions against the West. Afterwards, reported by the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), Chinese sanctions have become an increasingly popular tool for China in its geopolitical and ideological struggle against the West, and, in particular, the United States. These sanctions were mainly leveled on Western individuals and corporations that were either seen as interfering in China’s internal affairs or being critical of China’s human rights abuses in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Tibet.

Since the 2010s, China has promulgated a series of laws aiming to define and systematize sanctions. In 2016, China announced amendments to the Foreign Trade Law, which formally legalized the adoption of countermeasures in China in response to “discriminatory, prohibitive, or restrictive measures” taken by another country with respect to trade. In 2020, China published the Unreliable Entity List (UEL), a blacklist of counter-sanctions that allowed the government to impose punitive measures against foreign entities. These measures culminated in June 2021 when China adopted the Anti-Foreign Sanction Law (AFSL) in response to the sweeping imposition of sanctions by the United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and Canada against Chinese officials and corporations for human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Types of Sanctions

China’s sanctions fall under three broad categories:

Economic Measures

- Trade Restrictions

China frequently employs trade restrictions as a tool for coercion. This strategy involves deliberate efforts to disrupt trade flows and limit foreign access to the Chinese market through import and export controls. These restrictions can be implemented via the selective application of international regulations, targeted customs inspections, license denials, tariff increases, and unofficial embargoes.

- Investment Restrictions

China’s rise as a major global investor has empowered the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to impose restrictions on both outbound and inbound Chinese investments. These restrictions impact major trade deals, infrastructure projects, foreign direct investments, and joint ventures.

Political Measures

- State-issued Threats

State-issued threats, even when not followed by actual actions, serve as a form of coercion intended to influence the behavior of the target. Chinese ministries frequently issue official statements threatening foreign governments. These threats are often marked by ambiguous terms like “countermeasures” and “retaliation” to maintain a level of vagueness.

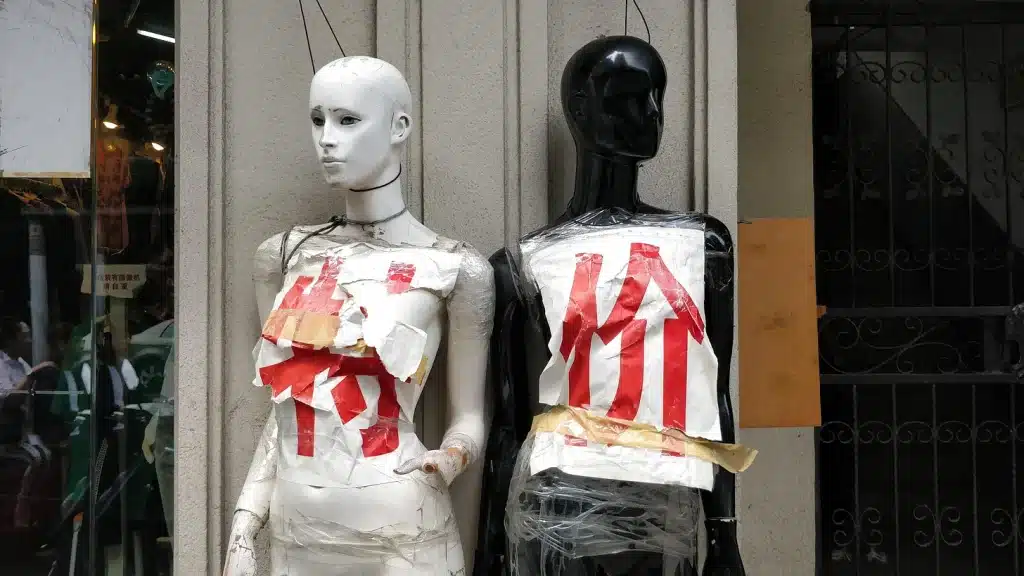

- Boycotts

China can retaliate against foreign governments without resorting to direct legal or regulatory measures by orchestrating commercial boycott campaigns through state and social media outlets. Additionally, it may fabricate the appearance of a popular boycott even when there is no genuine grassroots movement involved. For example, the Chinese government claimed that 1.4 billion Chinese citizens adamantly opposed the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests. However, much of the misinformation about Hong Kong was generated by the Chinese propaganda machine, as there was no organized boycott against the protests in Hong Kong overall.

Sanctions on individuals

- General Restrictions

Sanctions targeting individuals can include issuing travel restrictions, freezing property within Chinese territory, and banning business dealings with Chinese entities and individuals. These measures have been streamlined and unified following the implementation of the UEL and the AFSL.

- Arbitrary Detention or Execution

China has used arbitrary detention, indictments, and executions of foreign nationals as a tool for coercion against other states. This approach, often referred to as “hostage diplomacy,” leverages the CCP’s control over the judicial system. Due to the opaque nature of Chinese law enforcement and legal processes, understanding the pattern of these actions can be challenging. For example, after Canada released Huawei Technologies’ chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, China responded by releasing two Canadian citizens, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor. However, despite the Canadian government’s opposition, the death sentence for another Canadian, Robert Schellenberg, convicted of drug smuggling, was upheld.

Motivations Behind Chinese Sanctions

Individuals and corporations belonging to the United States and the European Union have been the primary targets of Chinese sanctions in the past decade. These sanctions are often symbolic in nature, representing China’s stance on sensitive issues, specifically China’s claims to territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea. These sanctions have been implemented as a form of retaliation against Western individuals’ or corporations’ perceived hostility toward or criticisms of China’s policies in Xinjiang and Hong Kong or interference of Chinese internal affairs related to the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea disputes.

Xinjiang

Even before the AFSL was formally adopted, China had already stepped up its sanctioning tactics. In 2021, China and Western governments dueled over human rights abuses in Xinjiang, with the West slapping sanctions on Chinese officials and businesses and China responding by imposing counter-sanctions. In January 2021, soon after former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo released a statement denouncing human rights abuses of Uyghurs, China declared sanctions on him and 27 other outgoing officials from the Trump administration, including Robert O’Brien, Matthew Pottinger, and Peter Navarro.

Two months later, Europe bore the brunt of China’s countermeasures against sanctions imposed against Beijing over human rights abuses in Xinjiang. The Chinese Foreign Ministry described EU sanctions as efforts to “rudely interfere in China’s internal affairs, openly violate international law and the basic norms of international relations, and severely damage China-EU relations.” In retaliation, China sanctioned ten individuals and four entities, accusing them of “seriously harming China’s sovereignty and interests and maliciously spreading lies and false information.” The sanctions targeted individuals within the European Parliament and the Political and Security Committee, as well as academics such as Adrian Zenz. Think tanks like MERICS and government bodies, including the European Parliament’s Subcommittee on Human Rights, were also sanctioned.

This dispute between China and the EU undoubtedly dealt a blow to the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), which had been under negotiation since 2014. As some scholars argue, to ensure that the CAI was finalized before President Joe Biden’s inauguration in 2021, China made significant concessions, especially agreeing to ratify the International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions banning forced labor. With the suspension of the ratification of CAI, China could no longer drive a wedge between Brussels and Washington on trade and investment issues and Western nations lost the hope of seeing better labor protections in China.

Hong Kong and Taiwan

In July 2021, China used the ASFL for the first time against the United States for supporting democratic reforms in Hong Kong. Among those sanctioned were former U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross as well as senior personnel in the Human Rights Watch, the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, the International Republican Institute, and the Hong Kong Democracy Council. These sanctions aimed to counter U.S. sanctions against Chinese officials who were involved in responding to the movement in Hong Kong during that time.

After the pro-democracy camp of Hong Kong was significantly weakened in 2021, the Chinese government began to intensify efforts to accelerate the “reunification” of Taiwan with Mainland China. From 2022 onward, more and more Western individuals and entities were sanctioned for pushing against this agenda. The most prominent sanction was against Nancy Pelosi and her immediate family in August 2022, shortly after she visited Taiwan. In April 2023, then-Republican House Speaker Kevin McCarthy held talks with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute in California, despite warnings from Beijing. As a result of McCarthy’s support for Taiwan, the leadership of the Reagan Library and the Hudson Institute, who presented Tsai with an award, were both sanctioned.

In 2024, China banned former U.S. Representative Mike Gallagher from entering China in response to Gallagher’s visit to Taiwan to support current Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te. Just recently, China implemented sanctions against Lockheed Martin, an American aerospace and defense manufacturer, over arms sales to Taiwan. The company’s senior executives are no longer allowed to enter China, and any assets they and the company have in the country have since been frozen.

Security Challenges

While most of China’s sanctions have no real teeth, China’s coercive measures against countries that are deemed to have threatened China’s core interests have long-term economic and political ramifications. One of the most prominent examples is China’s sanctions on the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 2017. In July 2016, the United States and the ROK proposed installing a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) anti-missile system to counter threats from North Korea. This move was swiftly condemned by China and triggered a range of coercive measures. Over the next few months, significant pressure was directed at the Korean entertainment industry. Additionally, official restrictions were imposed, such as tougher visa rules for Korean businesspeople, the suspension of all high-level defense talks, and the Qingdao city government canceling its participation in the Daegu Chimac Festival. The sanctions also targeted industries where South Korea has significant interests, such as tourism and cosmetics.

Australia is another country that has been significantly impacted by China’s coercive measures due to a variety of actions committed by Canberra, including its enactment of a legislation cracking down on foreign interference and its antagonism towards China’s militarization of the South China Sea. Additionally, Australia banned “high-risk” vendors Huawei and ZTE from the rollout of next-generation 5G telecommunications networks.

Starting in early 2020, the Chinese government significantly downgraded its diplomatic and trade relations with Australia because of its effort to launch an international independent investigation of the origins of Covid-19 virus. Initially, China detained Chinese Australians such as writer Yang Hengjun and TV anchor Cheng Lei. Subsequently, China suspended meat imports from four Australian abattoirs due to labeling and certification issues and imposed an 80.5% tariff on Australian barley, including a 73.6% anti-dumping duty and a 6.9% countervailing duty.

China’s campaign against Australia was likely the most notable example of coercive statecraft since its 2017 actions against South Korea over the THAAD system dispute. Initially, the measures taken against Australian exporters created panic and uncertainty due to their heavy reliance on the Chinese market. These tactics were designed to cause macroeconomic damage in order to incite political actors to apply pressure on the Australian government. However, as both sides have realized the pain their actions have inflicted on each other, they have taken steps to move on from the tensions.

The Future of China’s Sanctioning Strategy

While China’s sanctions could be seen as part of a broader “sanctions race” within the strategic competition between China and the West, overall China is not proactive, but rather retaliatory. Compared to economic sanctions that hurt businesses relying on the Chinese market, the politically motivated counter-sanctions, mainly targeting individuals and non-governmental entities, are merely symbolic, reactive, and therefore mostly ineffectual. China has yet to target key incumbent government officials of Western countries, though outgoing officials have been sanctioned. By avoiding punishing officials in current administrations, Beijing signals that it still wishes to maintain healthy communication with leaders of the United States and the EU.

Despite the increasingly more extensive nature of this rivalry, China has never struck the West with sanctions first. Chinese sanctions are always initiated in response to Western sanctions with relatively proportional counter-measures. Despite its soaring rhetoric, the Chinese government seems reluctant to take real, meaningful actions to escalate rising tensions. In other words, China’s sanctions are a form of “performative diplomacy” that aims to display strength, but fails to hurt the West.

As tensions between China and the West rise, we expect to see China continue to consolidate and codify its sanctioning methods. In the future, exchanges of sanctions are likely to be more frequent and expansive. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that China will commit to enacting sanctions with a real impact on the West.

Authors

-

Kay Zou is a student at Columbia University studying History and Political Science. Her research focuses on the global Cold War and Chinese elite politics.

China Focus Intern -