Interview with Donald Clarke: TikTok, the Chinese Legal System, and Suggestions for the U.S.

- Interviews

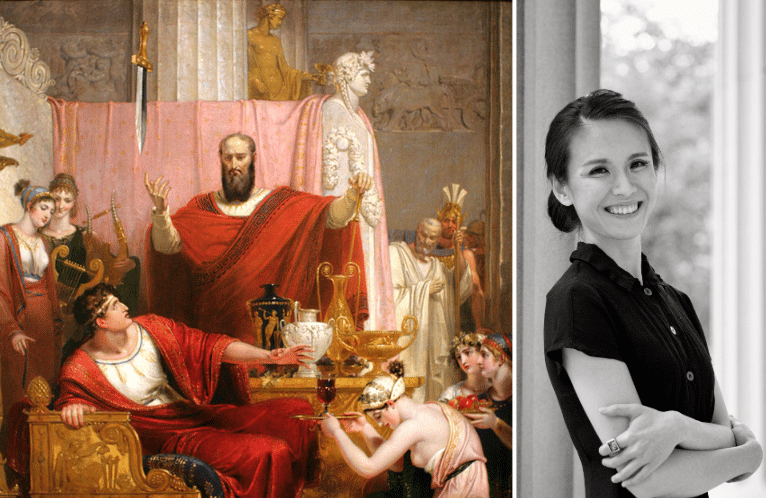

Miranda Wilson

Miranda Wilson- 04/19/2024

- 0

Donald C. Clarke, a specialist in Chinese law, joined the George Washington law school faculty in spring 2005 after teaching at the University of Washington School of Law in Seattle and the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, as well as practicing for three years at a major international firm with a large China practice. He is fluent in Mandarin Chinese, and has published extensively in journals such as the China Quarterly and American Journal of Comparative Law on subjects ranging from Chinese criminal law and procedure to corporate governance. His recent research has focused on Chinese legal institutions and the legal issues presented by China’s economic reforms. In addition to his academic work on Chinese law, Professor Clarke founded and maintains Chinalaw (formerly Chinese Law Net), the leading Internet listserv on Chinese law, writes the Chinese Law Prof Blog, is a co-editor of Asian Law Abstracts on the Social Science Research Network, and has often served as an expert witness on matters of Chinese law. Professor Clarke also speaks and reads Japanese and has published translations of Japanese legal scholarship in Law in Japan. He is also a member of the New York Bar and the Council on Foreign Relations. Read the U.S.-China Perception Monitor’s interview with Professor Clarke below.

To start off, how did you become interested in Chinese law and politics?

I first became interested in China through the language. I started studying Chinese language in college, and it was really through the language that I became interested in everything else. After I graduated from college, I went to China for two years. This was in the late seventies, right after Mao had died, but just before Deng Xiaoping had come back. It was quite an interesting time to be there because it was this transitional period between the old China of Mao and the new China of economic reform that we see today.

What are your thoughts on the House’s recent passage of a bill that would ban Tik Tok if not sold to an American company? What are the implications of the bill concerning the First Amendment?

On the First Amendment issue, I’d have to say I’m a Chinese law guy. I’m not a First Amendment guy. I’m not even an American law guy. I do have some ideas about it, but they’re not necessarily authoritative.

The main thing is I don’t find the arguments against the bill terribly compelling. For example, let’s suppose TikTok were owned by an American company and ByteDance proposed to buy it, and then Congress or the President, acting through some existing law, prohibited the sale. Would anyone say this posed a First Amendment problem? I don’t think so. I don’t see how reversing the timeline significantly changes the analysis. The U.S. has a long history of banning foreign ownership in certain sectors, including the media. Rupert Murdoch, for example, famously had to acquire U.S. citizenship in order to own his media properties in the U.S. I don’t see the idea that Congress could ban foreign ownership of TikTok as new or original, particularly because it’s a media platform.

Another objection to this bill is that it doesn’t say anything about all the other problems with media platforms, whether it’s abusive privacy policies, data, and so on. But again, I see that as an argument in favor of having those types of bills. I don’t see that as a reason to oppose this particular bill, which is about something else.

On the First Amendment issue, we need to break it down into two categories. First, there’s TikTok’s speech—perhaps better characterized as ByteDance’s speech—and second, there’s the right to speak and the right to hear speech on the part of TikTok users. It’s important to note that none of this involves the most dangerous type of speech regulation, which is regulation based on content. Nobody is saying that TikTok, ByteDance, or TikTok users cannot say certain things. The issue is whether people can make videos and listen to videos on TikTok at all, regardless of their content. Right away we’re talking about a lesser degree of severity.

Taking TikTok’s speech first, what is TikTok’s speech? It’s “speech” in the sense that TikTok’s curating algorithm can be characterized as speech. That’s not a dumb idea, and as far as I know, it would hold water under First Amendment jurisprudence. Nevertheless, it’s not the core idea of speech that the First Amendment is meant to protect. And again, because it’s really ByteDance’s speech, the speech of foreigners in the U.S. has never received the same level of protection as the speech of citizens.

Second, what about First Amendment rights of the users? Well, if TikTok is sold, then of course they can continue speaking and hearing speech on the platform. The new owners may have a different curating algorithm, but it seems very hard to make the argument that the First Amendment provides a constitutional right to any particular curating algorithm on a private speech platform.

Okay, what about if TikTok is not sold? It’s banned as a consequence. If that happens, then TikTok users are going to lose the opportunity both to speak and to hear speech on TikTok. That’s not trivial. On the other hand, however, let’s remember that before TikTok was around, there was a robust free speech environment in the U.S. and that environment still exists. Again, the ban is not about regulating content; it would just take the speech environment back a few years by eliminating a platform.

So does the fact that people can’t express themselves on TikTok mean that they have been robbed of the right to express themselves? That’s the important question, and I just don’t see that as a practical effect of a TikTok ban. I think people will still have many other avenues for expression of speech that are sufficient.

What’s the conversation like on the China side? Do you think ByteDance is going to be willing to sell?

I don’t know. I hear people saying China would not allow ByteDance to sell. And obviously, the curating algorithm is an important trade secret. If ByteDance were to sell TikTok, it would be worth much less if they just sold the brand and subscriber based and not the curating algorithm. ByteDance likely does not want to sell the curating algorithm because they’re going to want to keep operating in other countries. I don’t know what the calculation will be on ByteDance’s side. I would have to agree with those that say it’s not as simple as, “Well, ByteDance can just sell.” There are obviously complications, and I don’t know all the ins and outs of those. One angle I find puzzling is that of the basis for China’s assertion of legal jurisdiction to tell ByteDance that it can’t see a subsidiary. ByteDance is a Cayman Islands company. The fact that it operates in China of course makes it subject to Chinese government pressure, but that’s not the same as having legal jurisdiction. General Motors operates in China. Could China on that basis tell it not to sell its subsidiary operating in, say, Mexico?

Brookings released a report with experts claiming the U.S.-China relationship is the most consequential relationship for either country. However, tensions between the two countries have soared to an all-time high. How do you see this tension manifesting within the commercial law environment?

Problems of the business environment in China and commercial relationships are not confined to China and the U.S. European businesses are also feeling many of the same pressures and reacting in many of the same ways as U.S. businesses. We are seeing companies and their executives leaving and a general downturn in enthusiasm for investing in China.

Why is this happening? I think there are concerns about the personal safety of executives. There is the possibility of getting an exit ban: where you can’t leave China because your company has involved in litigation and possibly arbitrary detention. People feel that if somebody is out to get them, perhaps a business rival or someone they’re having a dispute with, criminal law can be weaponized in these commercial disputes, and they may end up in detention. That’s a serious concern because even if the probability is relatively low, you really, really, really don’t want it to happen. You don’t want to be the person that is the subject of the headlines about somebody who has been detained in China in a commercial dispute. These things keep happening, and although the government makes reassuring noises about how foreign businesses are welcome, at the same time, the Ministry of State Security is putting out media about how you should suspect all foreigners of being spies. Overall, it’s just a much less welcoming environment than it used to be.

In the legal area, we see foreign law firms operating in China setting up walls around their branch offices in Hong Kong. Recently, the American law firm Latham & Watkins announced that it is basically cutting off its Hong Kong branch from access to its servers in the United States because this is where law firms keep all their private information about clients and other matters. I assume they are taking these actions because the Hong Kong authorities could march into their branch office in Hong Kong and demand access to this kind of information. That makes it more difficult to do business because if you were using Latham & Watkins’ Hong Kong office, that’s going to make it difficult for them to communicate with the head office in the United States. There are laws in China now about data flows and restrictions on information that can leave China. There are punishments that can follow from the improper release of information across borders. The risk is pretty scary because, in the modern world, if you’re doing business in China as a foreign company, you’re going to have tons of data flowing in and out of the country all the time. That poses a very significant compliance problem that people are concerned about.

All those things together make it much more challenging to do business in China than it was before, especially when you couple that with the slowdown of the economy and fewer people interested in working in China. The number of American students at Chinese universities has gone down from something like 25,000 a decade ago to about seven hundred now—a drastic drop. Without new people coming through the pipeline that have the interest and the ability to work in a Chinese environment, that’s also going to be challenging.

In late February, Chinese lawmakers expanded Beijing’s state secrets law to include “work secrets.” What do you predict the consequences of this decision will be, particularly for businesses?

I’m glad you asked that because I think this is actually kind of a nothingburger.

What are work secrets, first of all? Work secrets include information about the ways public institutions operate that should be kept secret. If everybody knew about them, that would impair the functioning and the ability of the agency to do its job.

The second thing about the State Secrets Law is it’s not a criminal law and it hasn’t changed the criminal law. The statute called the Criminal Law is what puts you in jail for revealing state secrets. What the State Secrets Law mostly is about is duty. It’s about the duty of people to protect state secrets.

All the law says about work secrets is that they deserve protection under some forthcoming regulations, and the forthcoming regulations have not yet been issued. That’s why I say it’s a nothingburger, because the thing that gets you punished under the Criminal Law is things to do with state secrets—and work secrets are specifically defined as things that are not state secrets.

You recently published a paper called “Judging China: The Chinese Legal System in U.S. Courts,” which examines American courts’ conception of the Chinese legal system and how China-related cases are adjudicated. Your paper finds that courts often do not get good information, which impacts the justness of their decisions. Could you talk briefly about how you reached the conclusions of this paper?

For this paper, I wanted to look at cases in which, in order to resolve the case, U.S. courts needed to reach some kind of conclusion about the Chinese legal system as a whole. There are basically two types of cases where this happens. One is if somebody wins a court judgment in China and wants to enforce it in the U.S., so they come to a U.S. court and say, “I have my court judgment here, please enforce it.” And at that point, under U.S. law, when someone comes with a foreign judgment and wants to enforce it, the courts are not supposed to re-litigate the case. They’re supposed to see whether some basic requirements are met and then they enforce the foreign judgment. Well, in a case from China, the defendant might say, “No, don’t enforce this judgment. The Chinese legal system is unfair.” They’re going to raise all these defenses, and the plaintiff is going to say, “No, the Chinese legal system is fair, so please enforce this judgment.” The defendant is going to say it’s just like Canada or something. At that point, the courts have these two different sides. One says China’s legal system is terrible, and the other one says it’s great. They have to decide who they are going to go with.

The second type of case involves a legal doctrine called forum non conveniens (FNC). For example, there was an actual case of a helicopter crash in China, and the helicopter was made in the United States. Now, if you’re a victim or you’re the next of kin of the crash victims, you could sue in China. But you obviously would prefer to sue in the U.S., where the damage awards are going to be much higher. The defendant will say that it makes much more sense for this case to be tried in China because the accident was in China, the witnesses are in China, and Chinese law applies. That would be true, even if an American court heard the case, because they would still apply Chinese law. So they say to the court, “Listen, even though you could hear this case, it doesn’t make any sense. You should dismiss the case and tell the plaintiff to try their luck in China.”

For the FNC cases, I found several dozen. For the judgment enforcement cases, it was about a dozen. Then I looked at not just the judgments, but all the filings, too—the arguments that the lawyers made, the briefs they filed, if they had expert witnesses, what kind of declarations or statements did the expert witnesses make about the Chinese legal system, and so on. I looked at all of those factors and then I scored them on the basis of their quality. Generally, I found the quality of the information the courts were getting didn’t seem to make any difference in their decisions.

I also found, surprisingly, that the courts were not very welcoming to negative arguments about the Chinese legal system, which is a bit ironic because the Chinese government thinks that everybody in the U.S. government hates them. In fact, the judicial branch seems not to have gotten the anti-China memo. They often seem to demand a very high standard of proof. Of course, in an opaque system like China’s, it’s impossible to provide that kind of specific information. I found, somewhat unsurprisingly, that courts are not very good at figuring out the Chinese legal system. I teach a 39-hour basic introductory course on Chinese law at my law school, and that’s way more time than a judge could devote to learning about the Chinese legal system. It’s not surprising that they’re not doing a great job of it.

You also elucidate solutions to this issue in your paper. What do you believe are the most feasible steps the federal government can take to improve its understanding of the Chinese legal system?

First, there could be an authoritative executive branch report on how the Chinese legal system works. The closest that the executive branch comes is the State Department’s regular reports on human rights. But those reports are not about the Chinese legal system as a whole, particularly as it involves the treatment of things like regular tort cases as opposed to human rights issues. Therefore, they don’t directly address the issue that’s of interest to American courts in these cases. In general, when cases involve foreign relations issues, the courts generally defer to the executive branch. If the executive branch, whether it’s the State Department or the Department of Justice, came up with a report on what the executive branch thinks about the Chinese legal system, then that would be very helpful for courts.

Second, it needs to be made clear where the burden of proof lies on some of these issues. For example, in the FNC cases, under the applicable legal doctrine, it is up to the defendant to show that the legal system of the country they want to go to, in this case China, meets minimum standards of due process and fairness. I discovered that in practice, however, the courts tend to put the burden on the other side to show that the Chinese legal system does not meet these standards. Some kind of clarification of that process would be better.

Another proposal that has been seriously made is that dismissal on forum non conveniens grounds to foreign courts should simply be abolished. Originally, the doctrine was developed in a domestic context, where we’re talking about somebody being sued in Massachusetts saying, “Oh, you should really be suing me in New York.” So the Massachusetts court says, “Yeah, it looks good to us. Go to New York and try your luck.” Relatively recently, just in the past few decades, this doctrine has been expanded to allow dismissal to foreign courts. That is a totally different animal because we can expect Massachusetts courts to have some kind of understanding of how New York courts operate, but we can’t expect U.S. courts to have a comprehensive understanding of how Chinese courts operate. Indeed, while U.S. courts are constitutionally obliged to give full faith and credit to the court systems of sister states, they’re not ethically, morally, or legally obliged to give full faith and credit to the legal system of foreign countries or to assume that they operate just like the U.S. domestic legal system does. Thus, another feasible solution that has been made by serious scholars is just to abolish the doctrine that allows dismissal to foreign legal systems.

On a similar note, what do you think it is most important for the American public to understand about Chinese law?

That’s a hard question because I assume that the ordinary American doesn’t really have an accurate view of the Chinese legal system. Either they’re going to think, “Well, I guess it’s a legal system, it’s probably just like Canada,” or they’re going to think, “Oh, it’s a communist government so it’s awful.” But neither of these assumptions are based on actual information. I guess there are a few that might think it’s a socialist government and they love socialism, so they’re going to think it’s wonderful. But in all those cases, I guess I just don’t think the average person knows very much or thinks very much about Chinese law.

But that’s fine. It doesn’t actually matter because the average person isn’t dealing with the Chinese legal system. The only people that really need to deal with it are people doing business there or American courts. That’s what my paper was about: courts and government officials have to understand the Chinese legal system. If it’s someone that’s going to or dealing with China, I guess the main thing that I would want them to know is that the Chinese legal system functions along different lines from the U.S. legal system. In the U.S. legal system, if you have money and are well represented by a lawyer, then you can usually vindicate your rights and it will operate in a relatively predictable manner.

That is not the case in China. You have people like Jack Ma, the head of Alibaba, who isn’t short of money, but when he made disrespectful remarks about Chinese financial regulation he disappeared for several months. We see corporate executives disappear, it seems, pretty frequently. In other words, it’s not just that they are arrested on suspicion of a wrongdoing, which they may well be guilty of, but it’s just the fact that they completely disappear. That doesn’t seem justified even under China’s own legal provisions. If you go to China thinking that you’ll never get into trouble as long as you don’t do anything wrong and that if you do get into trouble, then you can call your lawyer, that’s an unrealistic expectation.

Also, there is a really fundamental difference in the two systems: Chinese courts don’t really see their mission as deciding on right and wrong according to the law; they see their mission as minimizing total social disruption. There are some recent studies of tort law that I’ve seen which look at tort cases in the Chinese courts, and very often they find the judges simply ignoring what the law would call for them to do, and instead just splitting the losses. Regardless of whether the defendant is in any realistic sense at fault, they just split the losses. They don’t want the plaintiffs who were demanding some kind of compensation to be too upset. These are not just outlier cases. Chinese courts see their job as making sure that nobody goes away too unhappy—and that includes the plaintiff and the defendant—and trying to find some resolution that will minimize total social discontent. If the law says something different, that’s a relatively secondary consideration.