President Carter’s Legacy and US-China Relations: The Jimmy Carter Forum on US-China Relations

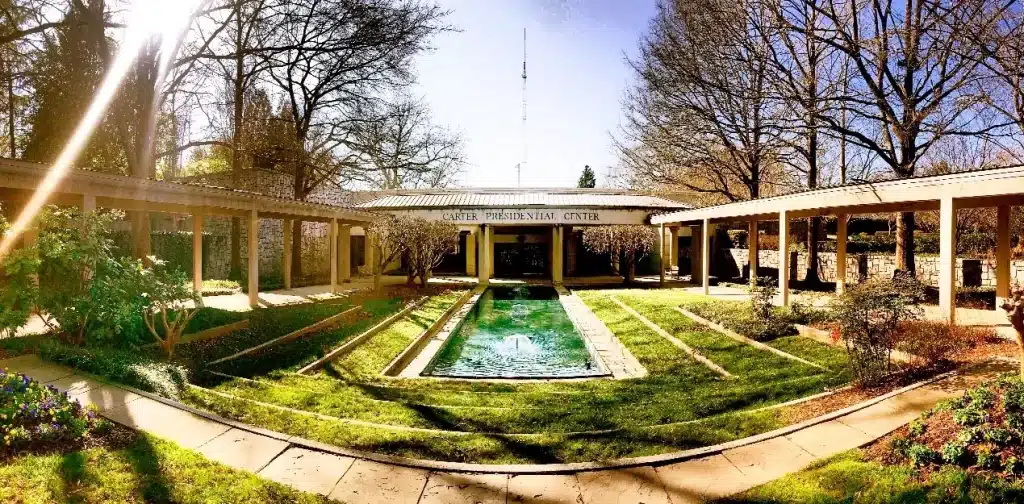

On January 9-10, 2024, the Carter Center held the Forum in Honor of Jimmy Carter and the 45th Anniversary of U.S.-China Relations. The event commemorated President Carter’s decision with Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping to normalize diplomatic relations between the U.S. and China in January 1979.

On the second day of the forum, the Center hosted private Track-II dialogues between American and Chinese experts on different issues in the bilateral relationship. These followed a plenary session featuring speeches by scholars and longtime practitioners in U.S.-China relations. With her permission, the U.S.-China Perception Monitor has published Elizabeth Knup’s speech at the plenary session. Ms. Knup is the Ford Foundation’s former Regional Director for China and now serves as Advisor to the Ford Foundation’s International Programs.

Good morning. It is my great pleasure to participate in this Forum to honor President Jimmy Carter and the 45th anniversary of the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and China. I want to thank President Carter, The Carter Center, and Liu Yawei and The Carter Center team for their consistent efforts to shed light on the complexity of US-China relations and the growing and diverse impact of China in the world. In a time of increasing misinformation, it is more important than ever to identify and elevate a wide range of informed points of view about China, US-China, and China’s global role, and to bring those ideas into respectful dialogue. Such dialogue elucidates the choices we face together in a complex and dynamic world. The Carter Center’s role in providing analysis and facilitating dialogue cannot be underestimated.

While the individual and the event we are commemorating at this Forum are of global importance, like many of us, I cannot help but also think of them in very personal terms: The 1980 presidential election was the first presidential election in which I could vote. I was passionate about the democratic process, participated in fierce debates throughout the campaign on my college campus and felt proud to cast my ballot for President Carter. He was, and remains, an important figure in my own political awakening. Then, and today, I am moved by his reminder to us of the responsibility we have to each other as citizens, by is commitment to upholding democratic principles, and by his life-long respect for human dignity and human rights.

And, as many mentioned yesterday, President Carter’s decision to re-establish US diplomatic relations with China in 1979 quite literally changed my life. That year I began studying Chinese, largely on an academic whim, giving no real thought to what would come after my graduation from college. I will not bore you with a long and winding tale, but I will share that last month I moved back to the US after living and working in China for 25 years, part of an even longer career devoted to the belief that mutual understanding between people in China and the rest of the world is a desirable, if elusive, goal. With understanding and the empathy generated in the process of seeking understanding, we are much more likely to find the solutions we need to build a more equitable and peaceful world. To be clear, understanding and empathy do not necessarily equal agreement. Best case, they create a mindset that makes more room for finding creative solutions. I do not know President Carter personally but my sense is that he is motivated by these same aspirations in all the work he has done, including his work related to China.

In the few minutes I have, I want to share a few thoughts, many of which were articulated yesterday, though I think they bear repeating. And before doing that I will reveal a fundamental assumption that underlies my thinking about China and US-China:that is: The United States and China are major global powers with different political systems and legitimate national interests. We can debate how legitimate specific articulated interests are, but as a starting point, each country believes its own interests are legitimate. Neither country is going to change its political system. Neither will diminish in influence in any foreseeable future. Any policy discussion in either the US or China or between the US and China must start with a recognition of this reality. I know this seems obvious. Sometimes it is useful to restate the obvious.

The excellent panels we heard yesterday and the Track II dialogues we will have today illustrate the depth and breadth of the current US-China relationship. The fact that we will have discussions across a range of diverse sectors is a concrete result of President Carter and Deng Xiaoping’s decision to create the opportunity for the United States and China to build a relationship based on substantive engagement.

“Engagement” has moved from a neutral descriptor of how human beings communicate and negotiate in the world to a word so freighted with political meaning tainted with failure and naivete that most people avoid using the term. If, as I believe, understanding is a precursor to finding solutions in any dimension of our social and political lives, then the only path to some level of understanding is through communication about interests and expectations, argument and negotiation, compromise, and acknowledgement of some areas of profound disagreement. Successful substantive engagement does not start with a defense of oneself and does not aim to change the other into an image ofyourself. Successful substantive engagement centers the problem to be solved and requires all parties to focus their energy on addressing that challenge. I have seen this work across my career: among the students at the Hopkins Nanjing Center in the aftermath of the Belgrade bombing incident, in difficult joint venture negotiations, and while navigating China for the Ford Foundation these last ten years. And, there are myriad policy negotiations and successes in the US-China relationship that bear this out as well.

Observing the ebb and flow in the US-China relationship over the past several years it is clear that when communication, argument, negotiation and consensus breaks down the risk of destabilizing conflict rises significantly. If, at the very least, we are seeking to avoid conflict—a low bar in my opinion—then substantive engagement is essential. And, if we are seeking more—meaningful progress on issues of global concern—then we must put a high value on substantive engagement not only between the United States and China, but with all parties with interests in and contributions to make toward finding necessary solutions.

Within this broader framework that posits that the US and China are major powers that are not going to change their natures fundamentally and that substantive engagement is essential, I see two dynamics at play:

The first is that much of the strategic and political discussion between the US and China today, while hugely important, is firmly rooted in the present and focuses narrowly onirritants in the bilateral relationship. Either the issue at hand is a present one—tariffs, investment barriers, military maneuvers—or, when trying to focus the conversation on imagining new strategic frameworks or on longer-term goals related to global governance issues, our bilateral conversations tend to be drawn away from the discussions of a possible future state and back into the present very quickly. The pull is always toward the immediate policy analysis, challenge or grievance. Even in some of the panels yesterday this phenomenon could be observed.

The second dynamic that has not been discussed much yet at this Forum is that China has and will continue to have significant influence and impact in the world, particularly in the developing world and increasingly on questions of global development.

The China many of us first came to know has changed. And for the purposes of these remarks I do not mean decreasing political openness and illiberal trajectories within China, which we tend to focus on and which are real. Rather, there are fundamental changes in Chinese society that are largely positive for the people of China, including reduced corruption in people’s daily lives, automation of mundane tasks creating more time for leisure, a cleaner environment, and real reductions in poverty. These changes improve many people’s lives and give the Chinese people and leadership confidence that their pathway to developmental success may be worth sharing with others on a similar path.

China’s influence grows from both its own geostrategic goals and aspirations it is advancing through development assistance programs – a push factor—and from countries actively seeking Chinese ideas and resources for their own developmental needs—a pull factor. In this push and pull process, some Chinese overseas finance and investment behavior is purely extractive and causes harm in the countries where the investments are made. In other cases, Chinese development ideas and resources have been shared productively.

Pulling together all the strands I have laid out: a belief in the benefits of mutual understanding, a defense of engagement as an essential modality, an observation that much of the US-China political and strategic bilateral discussion appears stuck in present tensions and fixed perspectives, and a recognition of the potential for China’s growing global influence to be positive: we should consider shifting the framework for our bilateral discussions from one that centers the immediate bilateral tensions to a broader framework, more inclusive of other stakeholders, that centers the challenges that require global leadership.

This idea does not deny the real problems that complicate the bilateral US-China relationship, nor is it intended to deter us from understanding, managing and even solving these problems. It is rather to widen the aperture. As Professor Wu Xingbo said yesterday, we should try to broaden the horizon of the conversation between the US andChina and focus our energy towards shared leadership in addressing global governance and international development challenges.

As we seek to improve global development outcomes, create a global AI governance systems, and combat the impacts of climate change, we should engage a range of stakeholders and assume that everyone, including the United States and China, have positive contributions to make. In so doing, we may find solutions and we may find that by broadening the horizon breakthroughs in stubborn bilateral questions also come into view.

Forty-five years ago, the need to establish a diplomatic relationship with China was critically important and hotly debated. The central question at the time was whether, when, and how to reestablish a formal relationship China and what might be the costs and benefits of so doing. “US-China relations” or “the relationship” – whether to have one, how to have one, the nature of it — was the key organizing framework for debate and discussion.

Today, it is a well-established and uncontested fact that the US and China have strong diplomatic ties. “The relationship” is not going to disappear and having bilateral relationship is not seriously in question. Now the question is how the US and China can work constructively in the world.

President Carter’s achievement 45 years ago was to act with courage in a visionary and far-sighted way. Today, we need more of this kind of vision. A vision that releases us from the disappointments of the past, encourages us to move beyond the intense debates of the present, and leads us to focus on building a more equitable and peaceful future.