3 Reasons to Ignore that Twitter (or Weibo) Poll

- Analysis

Michael Cerny

Michael Cerny  Scott Singer

Scott Singer- 08/08/2022

- 0

Michael B. Cerny is the associate editor of the U.S.-China Perception Monitor. Scott Singer is the co-founder and director of the Oxford China Policy Lab. Both are graduate students in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford.

Polls on social media may be a fun way to learn your friends’ favorite fast foods, but what can they tell you about US-China relations (or politics at all, for that matter)? The short answer: next to nothing, unfortunately.

There are (at least) three good reasons to avoid polls on social media, such as Twitter and Weibo.

Problem #1: Polls on social media are biased by their sampling frames.

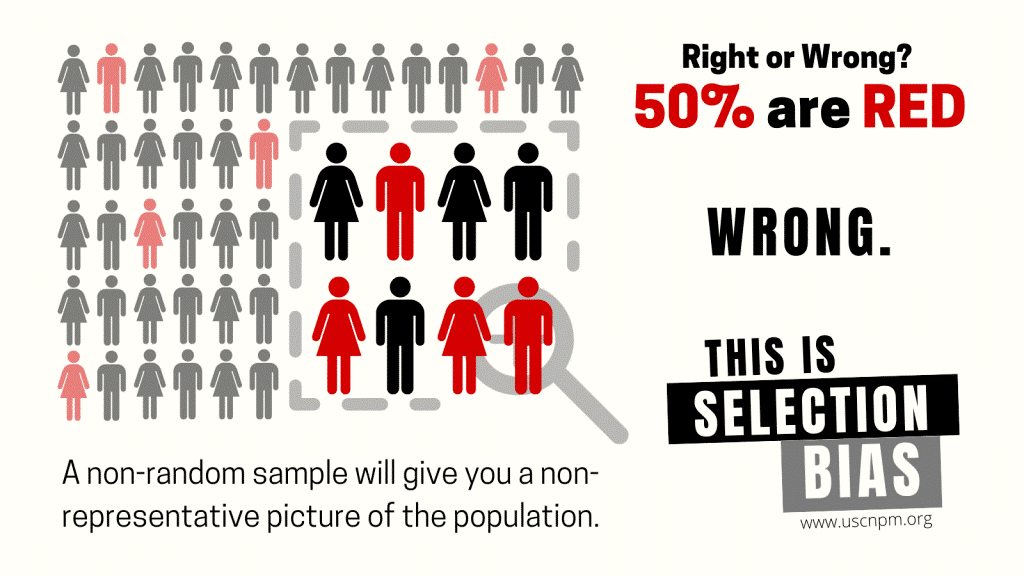

Imagine you wanted to find out which baseball team is most popular in America, but you only asked people as they were entering Yankee Stadium.

You might conclude that 70% of all Americans are Yankees fans, 20% are fans of whomever the Yankees are playing against, and 10% don’t care and think baseball’s a worthless sport (hi Scott’s mom). The point is: you might conclude there are far more Yankees fans than there actually are. This is one form of selection bias.

Conducting polls on Twitter suffers a similar problem: instead of a physical Yankee Stadium, we can imagine Twitter followers as a virtual community of people with similar views or interests. Imagine the Twitter following of Bill Bishop, for example, author of the leading China-focused newsletter Sinocism. Much like his newsletter, Bill’s followers likely fit a fairly similar profile: generally better educated, disproportionately concentrated in metropolitan areas (e.g., Washington DC, New York, London) and, above all, keenly interested in all things China.

If Bill were to field a Twitter poll right now asking respondents whether they’re interested in Chinese politics, we would expect most people to say ‘Yes, I am interested’. Similarly, if we polled only his paid newsletters subscribers, we’d expect this number to approach 100%.

In technical terms, Twitter polls are biased by their non-representative sample frames (in this case, the followers of the Twitter account fielding the poll). In professional polls, specialized methods are employed to ensure that the sampling frame approaches the characteristics of the population of interest. For example, some pollsters use a method called random digit dialing to approximate a random sample of the United States population.

Even methods used by experts are not a panacea, however, which brings us to the second problem with Twitter polls.

Problem #2: We cannot make claims about margin of error.

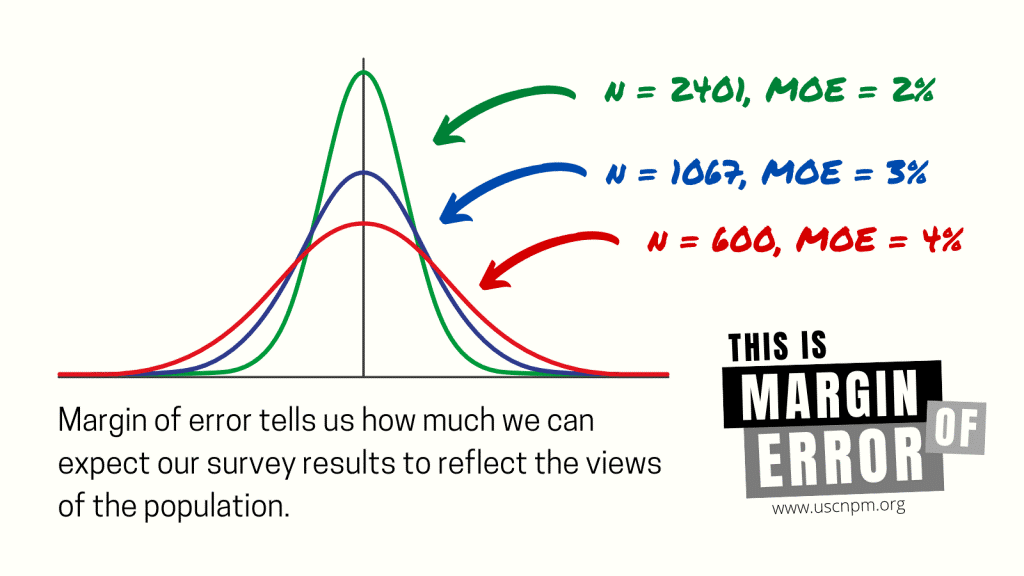

Suppose you’re trying to survey the population of China about their opinion on the United Nations. If we are going to use a sample of Chinese citizens to make a claim about Chinese public opinion, we need to make sure that the sample actually looks like the Chinese population. How does one achieve this?

In an impossibly perfect world, you’d compile a list of every Chinese citizen and then randomly select a few thousand of them and ask for their opinion. The reasoning behind random selection here is that every citizen would have an equal probability of being chosen for the survey regardless of their individual traits, such as their age, gender, education, income, and so on. Although it would be too arduous and expensive to survey everyone, statisticians have demonstrated how drawing randomly from a population produces a sample that gradually resembles the population of interest.

This allows us to calculate the margin of error, or the range of values that we’d feel confident the true population falls in. As a random sample gets larger, the margin of error gets smaller.

Unless you’re the Chinese government, however, it’s not possible to get a list of everyone’s names to randomly draw from. As a result, other methods must be used that produce samples which approximate the population. Oftentimes, these are only quasi-random or not random at all (e.g., quota sampling). This is where knowing our sample’s demographics can help ensure that, in the absence of true random selection, our sample still looks similar to the population.

However, in a social media survey, we tend to know nothing about the respondents, so it’s impossible to assess how our sample matches up to the population of interest. Our Twitter survey estimate could be spot on or ridiculously off depending on our sample’s demographics. To make matters worse, the margin of error applies not only to the total number of respondents to the survey, but also how the sample breaks down demographically. This can lead to very large margins of error that we have no method of evaluating on Twitter or Weibo.

Problem #3: Social media surveys are havens for response bias.

It’s not controversial to say that social media differs from real-world discourse in fundamental ways. Users are limited by character counts, accounts are often anonymous, and algorithms privilege emotion over logic. In many ways, social media does not encourage the care and attention needed to effectively survey how people think. In reality, social scientists toil away at question wording and survey design to ensure they’re precisely measuring what people believe and not what people might be (inadvertently) primed to think in that particular moment.

During this process, social scientists are acutely aware of non-response bias, a phenomenon that occurs when those who do not take a survey differ systematically from those who do. In nondemocratic countries like China, for example, it is well-documented that respondents might fear repression for expressing their true opinions about sensitive topics and, therefore, choose not to respond to surveys (or lie about their opinion, another phenomenon called preference falsification). As a result, responses to questions like ‘Do you support the Chinese Communist Party?’ tend to be heavily biased (studies that do not account for these phenomena report figures upwards of 90%, while more careful studies put this figure between 50% and 60%).

Non-response bias can also be caused by innocuous reasons, such as too long a survey questionnaire. On Twitter, we can think of other types of non-response bias. For example, some people engage with Tweets very little, and these lurkers’ opinions might systematically differ from those who are very active on Twitter – particularly in the China watching space – and engage with Tweets frequently. This might create situations where only people passionate and knowledgeable about the subject of a Twitter poll actually participate, which presents an important source of bias.