Will Xi’s Calls for ‘A More Lovable China’ Succeed? – Three Critical Considerations

President Xi Jinping called for a “credible, loveable, and respectable China” at a recent meeting of senior Communist Party officials. He suggested that the country “expand its circle of friends” through seeking to be “open and confident, but also modest and humble.”

Xi’s comments came off the back of China’s deteriorating relations with many states across the world – in addition to the United States, whose administration’s pivot from Trump era China policy has been less substantial than many had hoped, China has also ramped up its acrimonious rhetoric towards members of G-7, whom a Chinese illustrator recently portrayed through a memeified, satirical parody of ‘The Last Supper’. Chinese diplomats entered into spats with countries ranging from India to Australia, as they adopted a more strident, assertive international persona that has proven to be hugely popular to domestic Chinese audiences – with mixed reception, to say the least, abroad.

The practical necessity for China to be more lovable must be interpreted in light of the country’s battered international image abroad, as well as its deteriorating support amongst traditional allies or states otherwise open to collaboration with the country. Whether it be the ASEAN bloc (amongst which the favourability ratings of the United States have climbed considerably since Biden’s inauguration), or leading European states such as Germany and France, whose structural openness to trade with China was unable to overcome the turning tides in popular opinion which sabotaged the passage of the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between the European Union and China, there is little debate that China’s international reputation is suffering. Favourability ratings of China have declined sharply across a large number of countries, including Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, South Korea, and, of course, the United States.

Much has been written on whether, with his recent statement, Xi genuinely intends to adopt a fundamental shift or pivot in the country’s foreign policy. What I’d like to focus on, however, is a slightly different question – if China is indeed serious about making itself more lovable, well-received, and perceived as less of an alien threat in the eyes of the international community, what are its possible means of? How can China undo the damage wrought by its current diplomatic strategy? And how successful are these measures likely to be? There are three critical considerations to reflect upon here.

First, when it comes to state-driven discourse, China must tactfully separate the internal from the external. It is understandable – both as a means of instigating public support for the regime in the aftermath of the traumatic pandemic last year, and as a response to genuinely more confident mass sentiments amongst the Chinese public – that Beijing has become increasingly vociferous in its projection of nationalism in internal communications. Indeed, there is nothing inherently wrong with a voluntary population buying into nationalistic rhetoric that fits their tastes and worldviews.

Yet the problem arises, when inward-facing propaganda (neixuan) is conflated with outward-looking discourse (waixuan). The former has the distinctive telos of pacifying and satisfying domestic audiences, as well as enshrining the party’s effective rule in the eyes of its people. The latter – in theory – ought to play the role of bridging China’s differences with the world, communicating China’s unique story and historical trajectory in language and terms of reference that foreign audiences can understand. Diplomatic communications should neither be a matter of internal propaganda (neixuan), nor internal intelligence gathering (neican). Instead, the emphasis should be on amicable, open-minded, and forthcoming defenses of China’s national interests that do not unnecessarily grate the ears of foreign listeners – or, indeed, end up framing China as the ultimate threat to global order. Only by adopting an effective firewall that separates the external from the internal, can Chinese diplomats facilitate the rehabilitation of the country’s image amongst the undecided population internationally – those who lack well-formulated or consolidated impressions towards China, yet are repelled by what they deem to be imperious gestures and speech from the country. As Xi says, “it is necessary to make friends, unite and win over the majority, and constantly expand the circle of friends.”

Secondly, China would benefit from differentiating the signal from the noise. Certain Chinese diplomats, political theorists, and opinion leaders view any and all members of the “Western order” (itself by no means a homogeneous entity, nor should it be treated as one) as bent on undermining China’s progress and rise – as well as its underlying efforts in reclaiming a rightful place at the table.

This view mistakes the noise (of a vocal, and increasingly empowered minority, ironically due to the bellicosity of certain Chinese representatives) for the signal – there is an unmissable sense of uneasiness and insecurity amongst certain quarters in the West; yet does this necessarily equate a fundamental objection to China’s rise – tainted and promulgated by ethnocentric lenses? This strikes me as distinctly unlikely.

Not everyone in the West is bent on a direct conflict with China for the sake of it. As Bernie Sanders aptly notes in his recent Foreign Affairs article, “Organizing our foreign policy around a zero-sum global confrontation with China […] will fail to produce better Chinese behavior and be politically dangerous and strategically counterproductive.” China should not see winning the hearts and minds of the West as a lost cause – especially when doing so would only feed into the rhetoric of vociferous China hawks that are delighted by China’s playing into their very hands.

The West itself should not be treated as a homogenous bogeyman – even if there are plenty of such bogeymen amongst its ranks, including opportunists bent on employing ostensible criticisms of China’s domestic policies as disguised, racist dog-whistles. A vast majority of the Western populace remains open to China’s rise – their concerns and skepticism are rooted in their perceptions of China’s hyper-aggression. Some Chinese diplomats – in defense of their expressive belligerence – have argued that striking back is necessary as China’s means of “justified defence” against increasing pressure from the West.

Yet defence is only justified, if it actually works. Defense is only justified, if it is directed towards a genuine threat. If China views the West as homogenous and entirely threatening, then indeed, everything could count as a matter of defense. Yet this would be fundamentally erroneous.

Extreme, absolutist criticisms of internal matters and the political structure of China, are indeed forms of interference that must understandably be resisted by those who seek to uphold Chinese interests – but not all Western criticisms are like that. Worries raised over China’s economic and trade practices, its engagement with multilateral institutions, the security of its telecommunications conglomerates, and its labour rights record, can and should be addressed either through open, amicable, and well-evidenced refutations, or self-initiated corrections that strengthen, not weaken, China’s presence internationally.

Thirdly and finally, it is high time that diplomats and policymakers eschew the Manichean thinking that has evolved over recent years. The argument that states must either be expressly with, or are (potentially, clandestinely, or substantively) against China/the United States, is both theoretically flawed and practically counterproductive in enabling collaboration between the two countries in tackling some of the most urgent and salient issues in the world today.

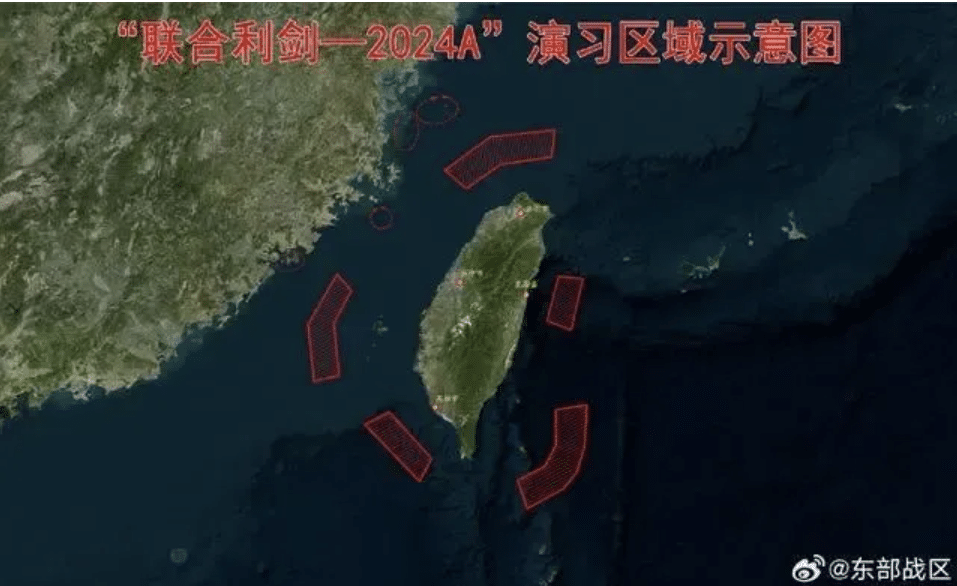

More importantly – even if one is unconvinced by the argument for collaboration, one should consider the alternative argument, one from risk mitigation. Miscalibration of each other’s intentions, misaligned expectations and deeply engrained misunderstandings could have devastating implications. Conflicts may spontaneously erupt across flashpoints ranging from the South China Seas, Taiwan, to the Sino-Indian border and Korean peninsula – for reasons largely independent of the intentions and beyond the control of the leaderships of the respective countries.

As Graham Allison once warned, the roots of a contemporary conflict between China and the United States may not be China’s inherent intentions or dispositions, but the fact that China is left with no choice but to respond to what it perceives to be American aggression. Washington must take note of this – but so should Beijing; totalistic confrontation cannot be the path forward. A more lovable international image requires China to grant greater leeway and breathing room to countries who are undecided, ambivalent, or strategically hedging between the West and China. Forcing neighbouring states and prospective allies to make up their minds is in the interest of neither China nor the world at large. The shades of grey in between are where genuine negotiations and compromises can and must be diplomatically brokered.

Suppose Beijing is genuinely keen on resetting its diplomatic approach, the above has highlighted that this would by no means be an easy process. Indeed, we should have every reason to be sceptical of those who argue that China needs only cosmetic adjustments to regain the hearts and minds of those that it has alienated over the years. It needs more than that – it needs strategic acumen and flexibility in face of an increasingly hostile international community.