US-China Misperception and the Rule of Law: An Interview with Jian Xu

Jian Xu received his Ph.D. in Political Science from Emory University and was previously a Pre-doctoral Fellow with the Democracy Program at The Carter Center. He will join Yale-NUS College as an Assistant Professor of Global Affairs in the summer of 2021.

Xu’s research focuses on international and comparative political economy, particularly government-business relations, the relationship between the rule of law and corruption, and the risk-mitigation strategies of multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in developing economies. His dissertation examined the impact of transnational legal orders on the rent-seeking behavior of public and private actors, and his research on how political connections affect commercial lawsuit outcomes in China was published in Comparative Political Studies. Xu was a recipient of the David A. Lake Award for the Best Paper Presented at the 2019 IPES Conference for his co-authored research on the importance of political resources for MNC litigation outcomes in authoritarian courts.

First, can you provide a bit of context about yourself, your academic experience, and your research interests?

Yes, sure. I got my undergraduate degree in Management in China. And then I switched gears and I decided to do political science–I am interested in government-business relations. So I went to Duke to do my master’s degree in political science and I focused on political economy. And then I decided that I wanted to do further research on the topic that I’m interested in and that is why I applied to Emory– Emory is really strong in studying the legal side of things, so to speak. I was really interested in the political, legal and regulatory frameworks governing international investment, international trade and multinational corporations activities. So my current research interest is in how multinational corporations and foreign investors deal with both sort of transnational regulatory frameworks, as well as the domestic regulations and laws and rules that could affect their business activities. So the trade war is definitely a hot topic, and also the rise of transnational anti-corruption regimes, especially led by the United States government.

There is now a global sort of oversight over multinational corporations for all activities abroad. So a Chinese firm bribery in Africa, or a European firm bribery in China, these kinds of things are now being put under a stronger and stronger regulatory scrutiny. I just defended my PhD, my doctoral thesis, and I’m going to be an Assistant Professor in Political Science at Yale-NUS College in Singapore. I’ll be mostly responsible for teaching the global affairs major and actually, I’m going to teach an anti-corruption class in the fall.

Can you talk about any research you conducted within China, and elaborate on why you felt it crucial to conduct the research in China?

Yeah. So there are a few projects I did over the last couple of years, mostly related to litigation in Chinese courts. I studied both how Chinese firms litigate in Chinese courts, as well as how multinational firms litigate in Chinese courts. Basically, the underlying idea was that in China, the rule of law is not well established and China doesn’t really have an independent judiciary as that enjoyed by the United States. Meanwhile, there are massive amounts of business transactions taking place in China. So when there’s a business transaction, there are contracts and so many procedures involved. Disputes are going to emerge, and there needs to be a way to manage these disputes–both for business entities to resolve disputes with private actors as well as with government agencies. So how does it work in such a complicated economy?

There is a misconceptions about the rule of law system in China, that “Oh, the courts are just dependent, they’re corrupt, they just listen to the party directors.” But in reality, that’s not going to work because the judges cannot just call their supervisor every time they’re hearing a case, right? It’s just too complicated. So my field was mostly about figuring out how judges resolve disputes, adjudicate their cases, and balance different priorities, both political priorities, as well as commercial economic incentives. Judges can’t just be political pawns all the time. They still have their own agency, their own incentives, their own preferences. They also need to do their job in a way that facilitates the market economy, or at least helps economic development to go through as planned.

My fieldwork was mostly on the ground, trying to interview the judges, look through the documents, the archives, and also listen to business executives and business associations–the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, for example. I wanted to hear what kind of difficulties that they face when they are litigating in Chinese courts, and what kind of uncertainties and risks are involved in these kind of authoritarian judicial processes.

What were some of the most challenging moments about conducting research in China? What about some of the most rewarding moments?

Yeah, so I did the interviews in the summers of 2017-18, and a little bit in the summer of 2019. And, as you probably know, that situation got more and more challenging over time. My starting point was in Hong Kong, and I got introduced to the judges, arbitrators, business executives, and government officials from Mainland China through connections in these Hong Kong universities and institutions. But I was just a PhD student. I didn’t have any name recognition or any reputation and so it was very hard.

I needed to rely on some intermediaries based on my close network and expand a little–sort of a snowballing approach. And then more and more, the judges could introduce me to other judges that they trusted. When I established some level of trust with them, they knew it was safe for them to tell me their stories. And also, I networked through my friends who worked for these multinational corporations, or who knew people at these multinational corporations. It was not easy to get the access, and there were many people who just refused to be interviewed. I also struggled with whether to leverage my U.S. background and connections, and when to hide them. I needed to alleviate concerns about, “Am I a spy, spying for the US government? What am I doing here?”

Regarding rule of law, what do you think are the most common misperceptions Americans have about the Chinese legal system? What would you like to tell those people about rule of law in China?

Yeah, so I think there are many areas of the law where the courts are functioning pretty well or at least pretty professionally, especially intellectual property rights protection. And there are more and more scholars starting to realize this, that business executives could actually sometimes rely on Chinese courts to protect their IP rights. It’s a notorious practice, or at least as reported in the media, that there’s intellectual property theft, that multinational corporations are very hesitant to bring their most valuable IP to the Chinese market and start their production lines there. But that’s only part of the truth. On the other hand, China has developed a highly efficient and professional IP adjudication system. It’s cheaper to litigate in Chinese IP courts, and it’s faster. And once your IP rights are recognized by the Chinese judicial system, it’s enforceable across the whole market.

In my opinion, that’s why a lot of foreign startups in California are increasingly willing to bring their disputes to Chinese court. In Shenzhen, for example, companies can get a very fast and inexpensive adjudication and then the award is enforceable across the whole market. It means that your IP product or any kind of your merchandise derived from that underlying IP asset can be sold in the Chinese market.

Meanwhile, if companies are bringing a court ruling from a California Court, that may not necessarily be recognized by Chinese courts. So actually, if your rights are recognized by the Chinese judicial system, then you can sell your products in a very large market. And it’s becoming more and more professional and less likely to be affected by political external influence. Part of the reason is that the government wants to encourage innovation, wants people to innovate and have their assets protected. It’s part of the national government strategy to lead in this new wave of technology, innovation. et cetera. And so the government wants people to have faith in the judicial system.

On that front, do these kinds of American technology companies from California and elsewhere know that they can go to China and get their IP rights protected in Chinese courts, or is it up-and-coming in the next few years?

Yeah, I think probably more of the latter because the development of judicial system is also a more recent thing–mostly after 2015. So it’s very recent, but it’s building up very fast and these American firms, they’re hiring Chinese lawyers, or they’re hiring American law firms who have established some kind presence in the Chinese market. Very well-known American law firms are also starting to specialize in IP litigation and intellectual property and other related areas in order to help their American clients navigate China’s complex judicial system. There are a lot of difficult nuances and it’s so unfamiliar for these American firms. But there’s a growing awareness that American companies can do this, and in a relatively reliable way.

Some political economists hold that economic growth requires a market-driven economy and a non-corrupt political environment. Such characteristics are arguably more likely in liberal democracies than authoritarian countries. Yet, China, which employs an investment-led growth model and continues to struggle with corruption, has enjoyed decades of rapid economic growth. Do you think continued growth under the current economic and political system is feasible? If not, what needs to change?

Yeah, so many scholars have written on this topic, writing about this paradox between rapid growth and rampant corruption. For me, I think that it depends on what you mean by corruption. I think the tricky issue here is that in China, there’s not a clear recognition of private property rights, because by constitution, the state can’t recognize private property. Because China is still nominally a communist country, private property is not a sacred right of the people. Then there’s a very vague delineation between ownership rights and controlling rights. It’s a very gray area where questions arise as to what kind of assets are state-owned, and what kind of assets are privately owned, or who has a legitimate claims to different assets, properties, etc?

So under these kinds of murky circumstances, it’s hard to say what is corruption. For example, say a business person who is running a factory makes a lot of money. And then the next day, a new administration comes to him and tells him that the licenses and permits he were granted were not legitimate, because the previous administration didn’t actually have the authority to issue them. And the business person would say, “But why? I made all this money, because you said I was able to do that.” And then because of this very uncertain environment, where the delineation between private property and the legitimate and illegitimate interests of public and private actors are unclear, I don’t know how we should characterize that sort of system of development in China.

But one thing is certain: there are still people–entrepreneurs and ordinary citizens–who are incentivized to work hard because they can retain part of their work or the fruits of their hard labor. But one day, they might just lose everything, so it’s still very uncertain. But still, the people are still working very hard. They’re trying to make a living in a very competitive market. When the market develops, the competition grows because there are so many encouraging so much production. And that magnitude of development is what has made China standout. Not necessarily the productivity, or the innovativeness of the economy, but just because there are so many people working hard to make a living in such a competitive environment.

And as long as the government doesn’t entirely kill people’s incentives to work hard, and to sort of expropriate everything they’ve earned, then people are still going to work hard. And they will produce a lot of things. And eventually, people are going to have greater consumption power. So multinational corporations will want to come in and produce in China to take advantage of the large market size. So yeah, I guess eventually people will want their property rights and as well as human rights, more broadly speaking, protected, if you want them to keep investing in the future in their children. And so there will be a greater tension I think, down the road. The Chinese government cannot expect to just sit on this large group of people and expect them to deliver tax revenue, to deliver your GDP, and not grant them their due rights and interest. And so I think the paradox still exists, and it needs to be reconciled or dealt with in some way down the road.

Has the Chinese government figured out a way to distinguish between types of corruption that are really damaging to economic growth and those that are less damaging? Can you even separate corruption into those two different buckets?

Yeah, so I think the government will try and do that because they have incentives to see the economy grow. And they realize that in order to have that outcome, the people must have a sense of security of their assets and their life. So the government definitely has incentives to provide public goods, for instance. But at the same time, the way the system is run is built upon this sort of unchecked or arbitrary exercise of government power. So if there’s strict control over government behavior, then corruption will of course be reduced. If there’s stronger judicial oversight and checks and balances, then corruption will be reduced. But then that betrays the purpose for an authoritarian government that it wants to gain, disproportionately, its lion’s share of the outcomes of development.

So there’s still very much an authoritarian regime that wants to expropriate or predate to some extent. And a lot of the ruling elites, who are not necessarily the most productive actors in the society, still want a larger pie in the market competition. So the rules will be bended and distorted in their interest. And the outcome of that is that there will be corruption, there will be all kinds of bureaucratic misconduct.

At the same time, that is going to hurt people’s incentives to deliver. So that tension to trade-off is also going to be there. You just can’t have both at the same time. You can’t want to grow the pie while keeping a greater portion of the pie for yourself. So, as you mentioned, there is a fine line there and it will be a very difficult thing for the government to balance. That’s why you see these policies shifting back and forth, between more protective and more encouraging, or more supportive versus more predatory.

More generally, can you talk about the most common misperceptions Americans have about China? Which of these were confirmed, and which were debunked during your time living and researching in China?

Yes, I think that’s related to the earlier topic that there are formal rules in China. So for example, you can see the media, or the more general propaganda apparatus releasing certain information that sounds very damaging, and very unfriendly. And there’s just this official, the veneer of formal rules and rhetoric and formalities. But then underneath, there’s a whole different dynamics.

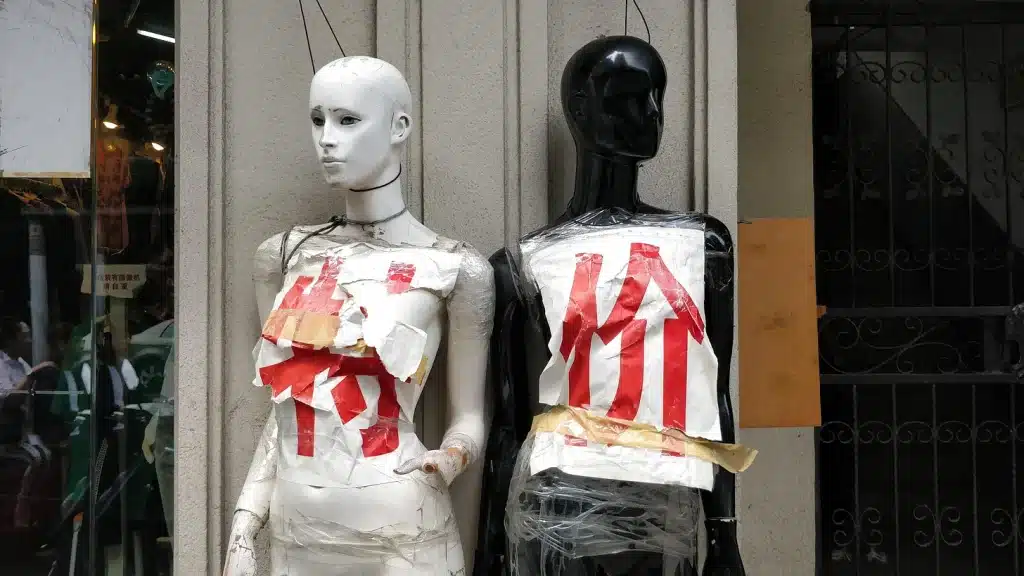

So if you’re just listening to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the government officials, they’re saying one thing. But then there’s a whole new different set of rules underneath that you really need to understand in order to fully comprehend the incentives and desires of the Chinese government or the people. And so you might see the resistance, the movement against these Nike brands over the Xinjiang issue, right? Lot of multinational brands have begun boycotting in China, and it seems that there’s a very angry crowd. But still, there are still issues that the people on the ground do not necessarily really want this. Sometimes they’re just following the slogan or the band wagon.

In reality, Chinese government officials still living their daily lives. They’re just very much like everyone else–a lot of them send their kids to the US to study and probably have their assets in the US. So I guess there are two different dynamics between what you hear, even if you’re in China, you interview these people and they will probably tell you the official rhetoric. But in reality, they are doing a totally different set of things driven by different logic.

That disconnect between government, and what’s happening on the ground, is really interesting. It’s something that people don’t always realize that they aren’t engrained in that system or that society.

Yeah. And I will also add that another misperception is that Chinese people are so different from Americans. But actually, they also strive to live this American dream life. You’ve probably heard about this, that the Chinese people are probably more American than Americans. They really believe in hard work and self-reliance, that you can strive to make a living and make a better future for yourself just by working really hard and following the rules. But they’re just less fortunate that in China because there’s this hierarchy above them, this rerouting regime that is taking advantage of their entrepreneurial spirit exploiting them in one way or another. But underneath, I think they really believe in this American idea that everybody either deserves a fair outcome or a fair future, if they put in enough work.

Conversely, as someone who has lived extensively in both countries, what are some of the most common misperceptions Chinese people have about the United States? What would you like to tell those people about American society?

I think for people who have never been to the US, they think of Americans as sort of looking down upon Chinese for being poor, for not speaking good English. Chinese people tend to think that Americans will show some hostility towards them, because for a lot of people that’s what the news and propaganda says–that America wants to beat China and take everything they have. But in truth, once they arrive on US soil and see ordinary Americans walking on the street, they change their view. I was very surprised when I first saw strangers just greeting and smiling at me in Durham, North Carolina. I was like, “I don’t know you, why you’re doing this, what do you want from me?” I witnessed so many people being friendly in general, for no reason at all. That was unimaginable.

On the other hand, Chinese people think that Americans are self-centered, so to speak, and that individualism means that Americans do everything out of self-interest. But I think in reality, I think the underlying spirit is that Americans are very rule-abiding, that there is respect for the rule of law. That’s why people can act not in violation of the law. I think that’s another misperception. A lot of Chinese people when they arrive in the US think, “This is the US, I can do anything I want.” And that’s not true. Firstly you need to respect the law, that’s more important than you exercising your free will. I think the strongest part of the American system is not necessarily that people have the liberty to choose what he or she wants to do. But that there is so much respect for the law that everybody has to play by the same rules.

And that’s not necessarily the case in China. Chinese people think that the rules are made by men, and can be changed by men. So there is not a very high regard for any type of rules, whether its domestic rules, international rules or laws. In truth, that’s why it is very hard, to build up the rule of law system. For example, if you visit Chinese communities in New York or other areas, those people have still retained much of their sort of old habits of disregarding rules because they are just made by men and not sacred.

In your view, what role does academic exchange–such as inter-country academic research or joint-venture educational programs–play in fostering positive US-China relations?

Yeah, there are a lot of American universities like NYU Shanghai, and Duke Kunshan and so many others that are engaging in collaborative initiatives with China. And I think it’s definitely going to help in the business world, because joint ventures between foreign enterprises and Chinese firms help by spreading best business practices, etc.

So similarly in the education area, students have more opportunities to be exposed to a world class education and the professors and scholarship in China. And at the same time, many controversies exist within educational exchange. For instance, there are rumors in the US about Chinese students and professors studying in the US acting on behalf of the Chinese government and not necessarily for pure academic reasons.

It’s also a different issue for China versus for the US, because America is still the greatest exporter of educational resources. So when Chinese students come to the US, they are buying into the US educational system and benefiting from that, and they are bringing this system and perspective back to China. So the US sees the risk of their open and liberal educational environment being taken advantage of by the Chinese government.

And so it’s very difficult for the US to sort of make a clear, distinction between these different types of activities. It’s tricky…I can’t think of a very good solution for the US government, because fostering these inter-country or inter-institution exchanges and dialogues is definitely helpful for promoting research. As people say, science has no boundaries and no sovereignty. But at the same time, these scientists have nationalities.

Numerous studies cite the benefits of this sort of academic collaboration. Meanwhile, worsening bilateral relations and the COVID-19 pandemic, obviously, have threatened to sort of undermine this exchange, and have also discouraged lots of scholars from continuing research in the opposing country. So in your opinion, what are some steps that could be taken in US domestic politics, maybe at the university or governmental level, or in US-China relations to encourage scholars to continue doing research in the other country?

Yeah, I think that the current mode of joint-ventures is probably going to be very effective. There are not many Chinese universities establishing joint ventures with American universities. It’s mostly the other way around. For example, the Yale-NUS College is Yale’s attempt to exporting the model of liberal arts education to Singapore. So, the liberal arts education kind of a novel thing to Asia in general. And in the long run, this kind of joint-venture model allows for more foreign investment and more foreign institutions to build partnerships with local entities. Joint-ventures also allow both countries to get the benefits of his foreign talents and foreign ideas. And so, in my opinion, this is a very helpful model.

Also, I think the US is still a very attractive place for global talents. Just imagine, during the Cold War, it was much more isolated. And the Soviet scientists, they were trapped inside the Soviet Union and helping the Soviet regime develop all these technologies. But once the gateway was opened, scientists have been more willing to help the US and contribute to US technological development.

I think it’s a very similar case to US-China relations today. In the current situation, our Chinese scientists and students are highly talented. But currently, the US government is not very willing to extend them a green card or work visa. And so they are sort of trapped in China, with the US not extending a welcoming hand. For the few Chinese students and scholars living in the US, they face all sorts of problems, including working permits, racism and other kinds of difficulties that just drive them back home saying, “Oh, I don’t really belong here. I am seen as the other.”

But if the US chooses to cultivate a more welcoming environment and become less bound by their political ideology, they could attract so many global talents. While the narrative among US policymakers is that these workers will serve the communist regime, that is very rarely the case. Chinese people are willing to seek a better life in the US if they have the chance. And they want their parents, their children to have better lives. And they’ve seen the inside and out of the Communist Party regime, they know what it’s doing. They might not necessarily agree with a lot of things their government is doing. In fact, they will probably find the American Dream more attractive if they can choose to live such a life.