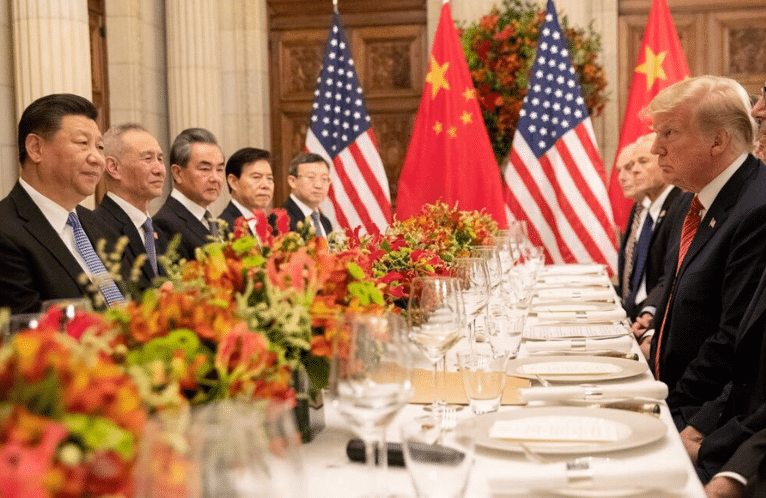

Opinion: Why A Trump Presidency Would Be Bad For Asia

As the race to the White House is heating up, Asian countries are paying close attention to the candidates’ foreign policy platforms. For the last few weeks, international headlines have focused on Donald Trump’s vision of a nuclearized Northeast Asia and his proposal to withdraw U.S. troops from South Korea and Japan if the two countries do not contribute more to the alliance. For the most part, scholars and strategists have denounced Trump’s plan. However, despite these negative remarks, primary results have shown that Trump is undoubtedly the Republican front-runner for the presidency. Even though the final result of the presidential campaign is not decided until November, Trump’s negative impacts on Asia are too clear to be ignored.

Trump’s foreign policy can be broken down into three main components. First, he seeks to limit the scope of U.S. foreign policy, from a major international player to an isolationist. Second, Trump wants to withdraw U.S. commitment to America’s East Asian allies, at the potential cost of Japan and South Korea acquiring their own nuclear weapons. And third, Trump wants to conduct foreign policy as a form of doing business, which means America must get benefits from any relationship with another country. A thorough examination at each of these components will provide a comprehensive look at potential consequences of Trump’s policies towards Asia.

First, the cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy since the end of World War II has always been the desire to construct and safeguard a liberal world order that every country is required to adhere to. Widespread U.S. interventions into global issues have strengthened the foundation for such a rule-based political order, and the presence of the United States has constrained the rise of new non-Western countries that seek to upset international standards and norms. Unfortunately, a Trump presidency is likely to pull America out of its role, giving rising powers like China greater leeway to impose its vision of order on neighboring countries. Moreover, such a decline in U.S. influence will send a dangerous signal to its East Asian allies that America is no longer willing to come to their defense, prompting them to resort to necessary security measures in order to make up for the loss of American commitment.

As a consequence of American isolationism, Trump has suggested withdrawing troops from South Korea and Japan and allowing the two countries to develop their own nuclear weapons. Trump’s intention is based on two major assumptions. First, upgrading and maintaining a large, modern conventional force is not an effective deterrent compared to developing a nuclear capability. Second, allowing South Korea and Japan to have nukes will relieve America of its responsibility as a “nuclear umbrella,” preventing the U.S. from engaging in a nuclear war with North Korea.

However, these two assumptions are unconvincing when more closely examined. American troop presence in South Korea is meant to prevent the escalation of conflicts between the two Koreas (deterring the North and constraining the South), and to provide U.S. Army with the capability to manage potential crises on the Korean peninsula. The withdrawal of U.S. troops is likely to damage the security structure and simultaneously reduce American operation capability in times of conflicts. Moreover, the lack of American security commitment will push South Korea closer to China, which gives China more incentives to enhance its military stature in East Asia, something the United States must avoid.

Second, allowing South Korea and Japan to develop nuclear capabilities will deal a critical blow to U.S. attempts at denuclearizing North Korea. Pyongyang is not willing to negotiate giving up its nuclear weapons now, much less when watching its enemies get their own. More dangerously, the escalation of a nuclear arms race coupled with American isolationism will undoubtedly increase the chances for miscalculations among Pyongyang, Seoul, and Tokyo. In this situation, maintaining the American security guarantee is the only way to prevent a war in Northeast Asia, a method that has been effective since the end of the Korean War.

The third component in Trump’s foreign policy will also impair the credibility of Washington’s “pivot to Asia” amid increasing China’s aggression in the East China Sea and the South China Sea. America’s pivot is meant to provide its allies and partners with reassurance of a stable political, economic, and security environment. This commitment requires the United States to conduct its foreign policy in a win-win manner with Asian countries, and Washington must demonstrate itself as a reliable partner in exchange for more interactions and cooperation. However, Trump’s business-style foreign policy will turn the pivot into a zero-sum game between the United States and Asian nations, which would raise doubts about Washington’s true intentions and consistency.

For example, Trump’s recent demand for Seoul and Tokyo to pay more to the coalition with Washington has turned a treaty commitment into a form of win-lose relationship, which prompted these states to clarify their contributions and reassess their affairs with the United States. Other Asian nations with interests in the U.S. pivot are likely to watch America’s relations with South Korea and Japan in order to determine how dependable Washington is. In the case of a Trump’s victory, the “pivot to Asia” will be a failed endeavor, causing Asian nations to seek for their own means of defense against China.

The 21st century has been described as the Asian century. Therefore, the United States need to adopt necessary policies to ensure peaceful economic, political, and security development of its Asian allies and partners. Donald Trump’s foreign policy of isolationism, nuclear proliferation, and zero-sum relationships is completely at odds with America’s “pivot to Asia.” If America wants to be great again, it will need to strengthen its commitment with the liberal structure it has created, and broaden its cooperation with regional players. Playing the role of a global peacekeeper is a must, not a choice for Washington.

Khang Vu is an international relations analyst from New London, New Hampshire, USA. The opinions expressed in the article are the author’s own.

By KHANG VU Apr. 7, 2016 on The Diplomat

Read more here