The Real U.S.-China Challenge: A Showdown in Cyberspace?

Late last Wednesday, the Department of Justice announced that Su Bin, a Chinese national living in Canada, had plead guilty to “participating in a years-long conspiracy to hack into the computer networks of major U.S. defense contractors, steal sensitive military and export-controlled data and send the stolen data to China.” Over several years, under Su’s direction, two hackers stole some 630,000 files from Boeing related to the C-17 military transport aircraft as well as data from the F-35 and F-22 fighter jets. The information included detailed drawings; measurements of the wings, fuselage, and other parts; outlines of the pipeline and electric wiring systems; and flight test data.

Su’s conspirators remain unidentified and at large. The 2014 indictment refers to the co-conspirators as “affiliated with multiple organizations and entities.” The plea announcement refers to them as “two persons in China” and says nothing more about them. But in documents submitted as part of Su’s extradition hearing, the U.S. government identified them as People’s Liberation Army (PLA) hackers. The documents included intercepted emails with digital images attached that showed military IDs with name, rank, military unit, and date of birth.

Still unknown is whether Su and the hackers operated on their own or were directed by Chinese government officials. Were they motivated by profit, patriotism, or some combination of the two? Much of the correspondence makes the hackers sound like PLA freelancers. Marketing themselves, they tell Su they were involved in previous attacks on defense industries as well as Tibetan and pro-democracy activists—targets with no commercial value but of interest to the government. In some emails, the hackers assure Su that the stolen files will not only give his aviation company, Lode Technologies, a competitive edge, but also help Beijing achieve its military modernization goals. Later Su warns the hackers about the size of the payout for their services, telling them that aviation companies are stingy.

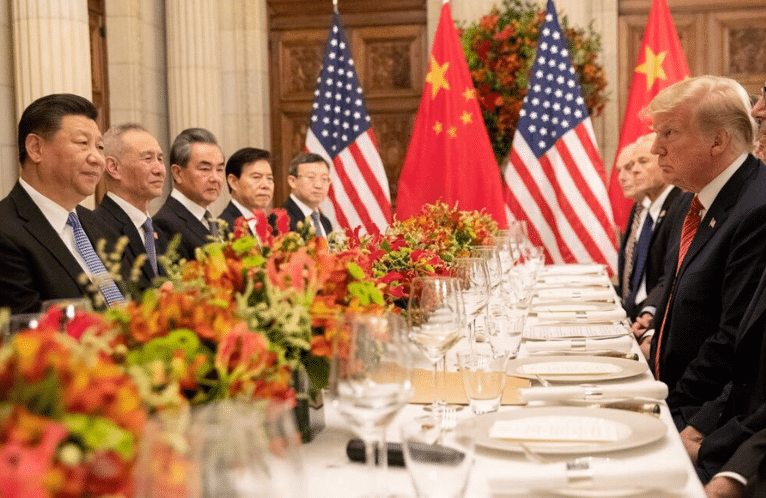

Is the next step the indictment of the two hackers in China? Last week Admiral Michael Rogers, NSA director and head of U.S. Cyber Command, told the House Armed Service Committee that despite President Xi Jinping’s September 2015 pledge to halt cyber espionage, “cyber operations from China are still targeting and exploiting U.S. government, defense industry, academic, and private computer networks.” Indicting Su’s co-conspirators might be a relatively easy way of sending a signal to China. The United States has already apparently identified them, and it seems likely that Su has provided even more information.

Making the situation even more interesting, the United States will reportedly indict about a half a dozen Iranian hackers for attacks on a New York dam and several banks in 2012 and 2013 (update since original post on CFR site: this has occured). No matter the short-term impact on U.S.-Iran and U.S.-China relations, Washington appears intent on trying to strengthen deterrence in cyberspace—to convince potential adversaries that the United States can over time attribute attacks and that there will be consequences for cyberattacks.

By ADAM SEGAL Mar. 27, 2016 on The National Interest

Read more here