Heavy Recruitment of Chinese Students Sows Discord on U.S. Campuses

Chutian Shao moved from China to the Midwest college town of Champaign, Ill., a few years ago. Some days, he says, it feels as if he hasn’t traveled very far at all.

On a recent Monday, the 22-year-old woke up in the apartment he shares with three Chinese friends. He walked to an engineering class at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where he sat with Chinese students. Then, he hit the gym with a Chinese pal before studying in the library until late into the night.

He recalls uttering two fragments in English all day. The longest was at Chipotle, where he ordered a burrito: “Double chicken, black beans, lettuce and hot sauce.”

At first glance, a huge wave of Chinese students entering American higher education seems beneficial for both sides. International students, in particular from China, are clamoring for American credentials, while U.S. schools want their tuition dollars, which can run two to three times the rate paid by in-state students.

On the ground, American campuses are struggling to absorb the rapid and growing influx—a dynamic confirmed by interviews with dozens of students, college professors and counselors.

Students such as Mr. Shao are finding themselves separated from their American peers, sometimes through choice. Many are having a tough time fitting in and keeping up with classes. School administrators and teachers bluntly say a significant portion of international students are ill prepared for an American college education, and resent having to amend their lectures as a result.

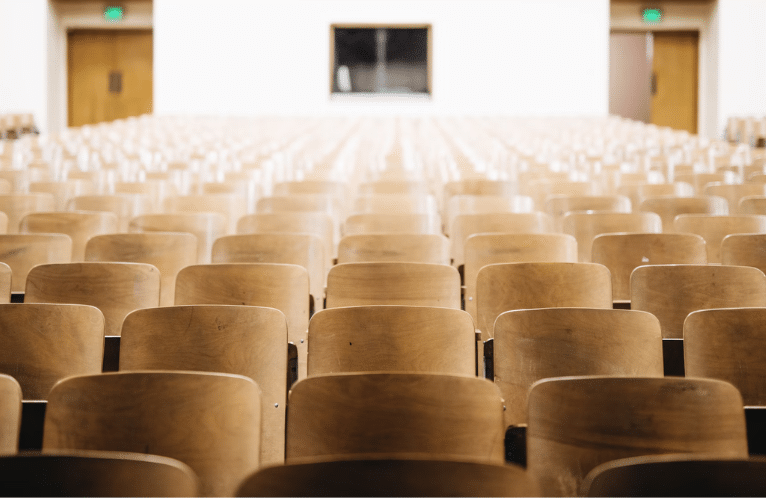

In a recent computer engineering class, Mr. Shao sat quietly in the back of a large lecture hall, dividing his time between Chinese social media on his smartphone and a lecture by Dave Nicol. He doesn’t remember ever asking a question in class.

Mr. Shao says he doesn’t want to expend the energy it would take to bridge the culture and language gaps. “The academic atmosphere is really good, which is the most important thing I care about,” he says.

He pledged a fraternity his freshmen year but soon found the drinking rituals and other demands took time away from his studies.

“I am majoring in electrical engineering,” says Mr. Shao. “It’s pretty intense.”

Mr. Nicol, the professor, says he can’t pronounce the names of many international students he teaches. He excises colloquialism from his lectures to avoid confusing the nonnative English speakers. When they do speak, he often asks them to repeat themselves. “Their questions are not always clear,” says Mr. Nicol.

Three years ago, administrators at Urbana-Champaign began traveling to China in the summer to start the orientation process early. Last year, in a bid to smooth over cultural gaps, it stopped separating international students into different orientations upon arrival.

“We’re trying to look at them less as a separate group that needs to be kept apart and mix them with other undergraduates,” says Martin McFarlane, director of international student services. “It’s a work in progress.”

Last year, Chinese students accounted for nearly one-third of all 975,000 overseas pupils and one-third of international-student growth at American colleges and universities, according to the Institute of International Education, a nonprofit provider of programs for international studies.

Schools generally talk up the influx of international students as an opportunity to prepare all students for a more global economy.

“The whole idea was to create cultural exchange,” says Catherine Liu, a Chinese-American professor of film and media studies at the University of California, Irvine. That said, “we’re getting students here without thinking enough about the quality of their experience.”

Rebecca Karl, a professor of Chinese history at New York University, puts it more starkly: She says Chinese students can pose a “burden” on her lectures, which she needs to modify for their benefit.

Many Chinese students “are woefully underprepared,” she says. “They have very little idea what it means to be analytical about a text. They find it very difficult to fulfill basic requirements of analytical thinking or writing.”

The unhappiness appears to be mutual. Lingyun Zhang, 25 years old, came from Beijing to study business at Oregon State University. She landed in an accounting class with 11 other Chinese students and four Americans.

“I didn’t expect to go abroad and take classes with so many Chinese people,” she said during a recent lecture on the U.S. regulatory environment.

One of her Chinese roommates, determined to interact more with Americans, recently transferred to a small university in Ohio, says Ms. Zhang.

Other students say the school isn’t doing much to help them secure internships or jobs—or even teach them how to compile a résumé.

“How can we fit in this environment? How can you write a résumé, application, and how does this procedure work?” says Haiyi Li, from Guangzhou, China, a 21-year-old Oregon State student.

A decade ago, facing falling state financial support, Oregon State decided it needed to attract more students from outside the U.S. State appropriations per full-time college student have fallen 45% in the past five years.

In an effort to jump start international enrollment, Oregon State launched an English-immersion program in partnership with a private British-based firm called INTO, which accepts students with limited English skills and aims to prepare them for regular course work.

The program is housed in a $52 million state-of-the-art facility, paid for by Oregon State, which boasts a store stocked with organic and Asian food products, eco-friendly plumbing and solar panels on the roof.

“Our primary goal was to double the number of international students in five years,” says Chris A. Bell, an engineering professor who was on the team that launched the INTO partnership. “We had blown through that in four.”

Oregon State’s international population surpassed 3,300 last fall, up from 988 in 2008, the year before INTO began operating. The revenue has enabled the university to add 300 tenure-track professors and expand overall enrollment to nearly 29,000 from about 19,000 during the same period.

One concentration, the school’s accountancy masters of business, now has more Chinese than American students, says senior professor Roger Graham Jr. That raises questions, he says, such as, “Do I stick with the original learning objectives or modify them” to suit the needs of Chinese students?

Yibo Fan, from Wuhan, China, came through the INTO program, but struggled when he moved into the main school. He failed one engineering class, he says, which he plans to retake and pass when his English is stronger. He declined to divulge his current GPA.

Mr. Fan, 21, prefers to sit in class beside Chinese with whom he confers when he misses something. He occasionally asks instructors follow-up questions after a lesson. Some are patient with him, he says, “but not everyone.”

He says he has made two American friends since arriving in 2013: his former roommate, Jonathan Avery, with whom he occasionally communicates by text; and a fellow member of a local car club he met online.

“Before I came here, I would like to have many American friends,” he says. “After I came, I found language and culture is a problem.”

Mr. Avery, an Oregonian who hasn’t traveled outside the U.S., says Mr. Fan was the first Chinese person he met. “I really appreciated the exposure,” he says.

With the concentration of Chinese students so high, it is more likely for them to have a fairly insular campus experience, compared with students from countries with fewer numbers.

Provost Sabah Randhawa says Oregon State has decided to “slow down” its intake of Chinese students and tap new markets, such as Africa, Europe and Latin America, to make the campus more diverse.

The school strives “to provide greater interactions of international students with the broader university,” he says. “At the same time, it is good to get our students’ perspectives on their experience, so we can continually improve and enhance our program.”

Other schools, such as Miami University in Ohio, have considered raising some English-language requirements to ensure students have strong enough listening and speaking skills to engage in classroom discussions.

That strategy, though, has seen mixed results elsewhere. In 2012, the University of Pittsburgh raised its minimum score on the Test of English as a Foreign Language, or Toefl, from 80 to 100.

Juan J. Manfredi, vice provost for Undergraduate Studies at Pitt, says he decided to make the change after meeting with a student who had been struggling academically and discovered he couldn’t communicate with the student without a translator. The result was a 25% decline in the number of international students who enrolled.

“We knew we were taking a chance,” says Mr. Manfredi, who says the number of students has since rebounded. “I think it worked out well.”

On some campuses, wealthy Chinese students stand out for their extraordinary opulence—and fuel resentment in the process.

Ashley Yao, a student at Stony Brook University in New York, speeds to classes in a tricked-out BMW X5 M sport-utility vehicle. The 25-year-old wears haute couture and hangs out with other wealthy Chinese-born university students who drive candy-colored Lamborghinis, Ferraris and McLarens.

Ms. Yao, who lives in a four-bedroom house her parents bought for her, says she finds it difficult to connect with the U.S. students on campus.

“American students have a certain idea about how Chinese students should be,” she says, adding, “It feels a little hard to become part of American society.”

At Urbana-Champaign, Chinese students tend to gravitate to certain courses where they can find the primary reading in their native language, says Elizabeth Oyler, director of the school’s Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies. As a result, roughly half of the students in the East Asian Studies courses are Chinese—a tilt that has altered the overall dynamic. Many struggle to understand lectures and produce college-level written work.

“In a lot of cases, they don’t take part in the discussions,” says Ms. Oyler. “It can be problematic.”

The school now offers seminars for faculty and staff led by international students and scholars to help explain cultural norms. It has also tackled campus socializing, with a “sports 101” program where overseas students meet athletes from the football, basketball, baseball and hockey teams.

Mr. McFarlane, the director of international student services, acknowledges the school isn’t “where we need to be” with regard to integrating international students. But that doesn’t mean we’re not proud of how far we’ve come.”

By DOUGLAS BELKIM and MIRIAM JORDAN Mar. 17, 2016 on the Wall Street Journal

Read more here