China’s Princelings Urge Patience As President Xi Jinping Seeks ‘Complex’ Change

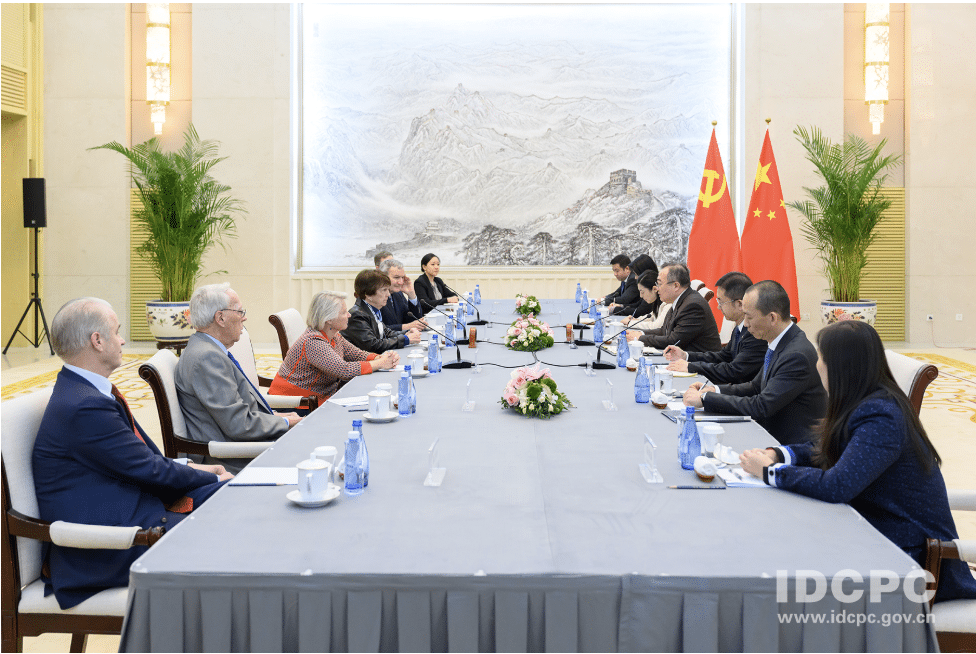

The atmosphere in the gilded banquet hall at Beijing’s State Guesthouse was festive on Sunday afternoon, as the children of Communist Party revolutionaries gathered to celebrate the Lunar New Year and praise the most prominent member of their class, President Xi Jinping.

The annual meeting of the Yanan Children’s Friendship Association began with traditional singing of classics from the party hymnal.

“Without the Communist Party, there would be no China,” the largely silver-maned crowd of hundreds of “princelings” sang in unison. A calligrapher showed attendees how to combine the characters for Xi’s “Chinese dream” slogan with the traditional new year blessing of “good fortune.”

The celebrations gave way, however, to stark warnings from group founder Hu Muying, who called on attendees to stay faithful amid the “complex and fluctuating situation” confronting China three years into Xi’s rule.

The party faced ideological “chaos” and a graft problem that needed more time to fix, Hu said. Meanwhile, “hostile Western forces are containing, slandering and doom-saying [predicting disaster for] China, and working hard to subvert the communist and socialist regime”, she said.

Hu’s group is the largest representing the offspring of revolutionaries who founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949, with some growing up to hold top positions in government and finance.

A number of smaller princeling organisations were also in attendance. China’s President Xi Jinping is carrying out far-reaching reforms, including overhauls of the military, the patronage system and state-run industries. Photo: AP

China’s President Xi Jinping is carrying out far-reaching reforms, including overhauls of the military, the patronage system and state-run industries. Photo: AP

The clubs see Xi, whose father was Vice-Premier Xi Zhongxun, as one of their own, and Hu has made her annual speech a call for support for Xi since he took control of the party in 2012.

“We must seriously understand the strategic blueprint of the central leadership and catch up with Secretary General Xi’s footsteps,” said Hu, whose father was the longest-serving secretary to Mao Zedong.

“Don’t be impatient and don’t be pessimistic. We must have the determination to fight this protracted war.”

The reference to “protracted war” was a nod to those in the party elite who may be anxious as China’s economic growth cools to the slowest pace in a quarter century and Xi carries out a far-reaching overhaul of government, industry and society.

The phrase is taken from the title of a group lecture delivered by Mao in 1938, during one of the darkest periods in Chinese history as Japanese troops marched across the country.

In “On Protracted War”, Mao argued China would prevail only after an arduous struggle, rebutting both those who underestimated Japanese strength and those who saw the invader as invincible.

“Ultimately, the enemy will lose and we will win, but we shall have a hard stretch of road to travel,” Mao wrote from his stronghold in Yanan, more than seven years before Japan surrendered and 11 years before the Communists defeated Nationalist forces in the Chinese civil war.

The remark also acknowledges the prospect that Xi’s reforms – including overhauls of the military, the patronage system and state-run industries – could take many years to complete.

The party is trying to implement changes without spurring the sort of mass unrest that could loosen its 66-year grip on rule.

Strains on the government have increased amid a US$5 trillion stock market rout, predictions of currency declines and disputes with the US over cyberspying, the North Korean nuclear threat and China’s military expansion in the South China Sea.

Mao’s wartime lectures may also provide clues as to why Xi may be increasing pressure on state media to conform more closely to the party line. Back then, Mao blamed the party’s own propaganda authorities for failing to educate the masses about the challenges facing them.

Hu’s father, Hu Qiaomu, once oversaw the party’s propaganda efforts.

People applaud as Chinese President Xi Jinping (centre) talks with editors in the newsroom of the People’s Daily in Beijing last Friday. Photo: XinhuaOn Friday, Xi visited the headquarters of China Central Television, thePeople’s Daily newspaper and Xinhua news agency, where he urged journalists “to put political direction above anything else”, according to Xinhua.

People applaud as Chinese President Xi Jinping (centre) talks with editors in the newsroom of the People’s Daily in Beijing last Friday. Photo: XinhuaOn Friday, Xi visited the headquarters of China Central Television, thePeople’s Daily newspaper and Xinhua news agency, where he urged journalists “to put political direction above anything else”, according to Xinhua.

All media outlets bear the surname “party,” Xi said, meaning they’re offspring of the same institution.

“We have the responsibility to protect the country’s social environment and to spread positive energy, especially in today’s China, when the country is in a transition period,” Zhao Cheng, editor-in-chief for Baidu, said in a discussion held by the Cyberspace Administration of China on Monday to review Xi’s media policies, according to a transcript.

To explain what’s at stake, Hu borrowed another phrase from Mao, this one from a 1930 letter criticising pessimism within the party. “We have to hold a strong belief: a single spark can start a prairie fire,” she said.

Feb. 23, 2016 on the South China Morning Post

Read more here