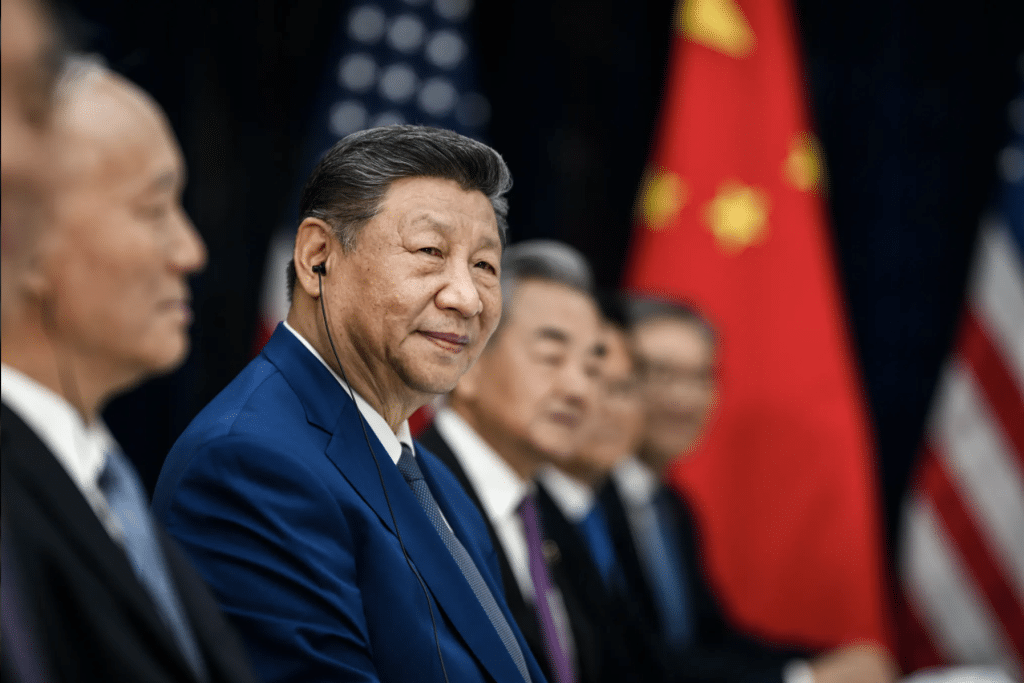

How Capable Are the U.S. and Japan of Intervening in a Taiwan Conflict?

How Capable Are the U.S. and Japan of Intervening in a Taiwan Conflict?

- Analysis

The World from Multiple Angles

The World from Multiple Angles- 12/03/2025

- 0

(Editor’s note: The original Chinese version of this article was published on December 2 on the WeChat account “The World from Multiple Angles.” The piece explores a hypothetical scenario: if war were to break out in the Taiwan Strait, could the PLA manage the battlefield? Could it prevail? The article contains many military figures that we are unable to verify. US-China Perception Monitor has translated the English version for readers’ reference. The Chinese version has already been read nearly twenty thousand times.)

Before diving in, questions such as whether Beijing would launch a military operation, when it might happen, and whether the United States and Japan would intervene are fundamentally political. They have no definitive answers. This article therefore proceeds from a simple premise: If a military campaign were truly launched, and the U.S. and Japan were determined to intervene.

Japan does not have the capability to intervene on its own. The United States also needs a forward operating base. In practice, they would either intervene together or not at all.

Below is a rough assessment of how much air and naval power the U.S. could pull together.

U.S. Air Power

The U.S. Air Force—including the Air National Guard and the Reserves—currently operates roughly 1,800 fighter aircraft, plus around 200 A-10 attack jets (which are being phased out in favor of the F-15EX and other types). The largest fleet is the F-16 with more than 800 aircraft, followed by roughly 500 F-35s, around 300 F-15s, and about 185 F-22s.

Assuming ongoing retirements (F-15s, F-16s, F-22s, A-10s) are offset by the growth of the F-35 fleet, we can estimate the total force remaining stable at around 2,000 combat aircraft in the coming years.

These aircraft are globally deployed, with major concentrations in North America, Europe, and the Indo-Pacific.

For the Pacific, U.S. Indo-Pacific Air Forces oversees the 5th, 7th, and 11th Air Forces:

- 5th Air Force (Japan): 18th and 35th Fighter Wings

- 7th Air Force (South Korea): 8th and 51st Fighter Wings

- 11th Air Force (Alaska, Hawaii, Guam): 354th and 15th Wings

A U.S. fighter wing generally consists of two fighter squadrons, each typically with 24 aircraft, plus supporting units. In practice, wing strength varies slightly, but the differences are minor. Counting roughly 50 fighters per wing, these three air forces collectively field around 300 aircraft.

If the U.S. intervened, these units could be deployed. The U.S. could also bring in Marine Corps F-35Bs, plus at least one or two additional fighter wings from the mainland, raising the total available force in theater to roughly 400 fighters.

Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force has more than 300 fighters. After retaining a portion for homeland defense—particularly against Russia—the remainder could be shifted south.

Together, the U.S. and Japan could field more than 600 fighters, supported by electronic warfare aircraft, airborne early-warning planes, and tankers. Given that F-35 production is accelerating, it is reasonable to assume that within a few years roughly 70 percent of these 600 fighters would be F-35A/B variants, with the rest being F-15s and F-16s.

This calculation does not include potential contributors such as Australia or the United Kingdom, which historically have shown little inclination to sit out if the U.S. and Japan decide to intervene.

Initial Deployment Challenges

In the early phase of intervention, U.S. and Japanese aircraft would not immediately mass in Okinawa or other frontline bases, which are too close to mainland China and vulnerable to PLA missile strikes or H-6K bomber attacks.

Instead, they would likely stage from southern Philippines, Japan’s main islands, and Guam, awaiting the outcome of the initial naval contest between U.S. forces, air assets on Guam, and the PLA’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) fleet. Only after that battle would they decide on next steps.

If the PLA Navy holds the line, U.S.–Japan air forces would find themselves too far from the fight to be effective. If the PLA Navy is defeated and forced to fall back toward the mainland, U.S. carrier strike groups would move toward the First Island Chain, and U.S.–Japan aircraft would begin dispersing to bases along the chain.

Thus, the PLA Navy’s performance in A2/AD operations would play a decisive role in determining the entire course of the war.

The United States has spent recent years returning to the Philippines and gaining access to numerous ports and airfields. These facilities would almost certainly be used during a conflict.

Anti-access operations would be immensely difficult.

U.S. Naval Power

The aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN-68) is scheduled to retire in 2026. Because construction of the follow-on Ford-class carriers has lagged, the Eisenhower (CVN-69) and Carl Vinson (CVN-70) will likely see their service lives extended.

Assuming the U.S. Navy maintains a 10-carrier fleet, at least three carriers can be kept deployed at any given time. After six months of surge mobilization and accelerated training, the U.S. could likely make five carriers available for operations.

Leaving one or two for commitments in Europe and the Middle East, at least three carriers—with more than 30 surface combatants and over 20 nuclear attack submarines (Virginia- and Los Angeles-class)—could be directed toward a Taiwan contingency.

Given the limited maneuvering space in the South China Sea and East China Sea, U.S.–Japan naval forces would most likely operate primarily in the Philippine Sea, where they have ample room to maneuver.

The PLA Navy’s expected force by the late 2020s to early 2030s is well-known: three aircraft carriers, at least 60 destroyers, 50 frigates, and around 40 nuclear attack submarines.

Naval warfare is extraordinarily complex, and I do not have the ability to model a full-scale naval campaign. The following sections therefore offer only a simplified, board-game-style discussion of possible dynamics.

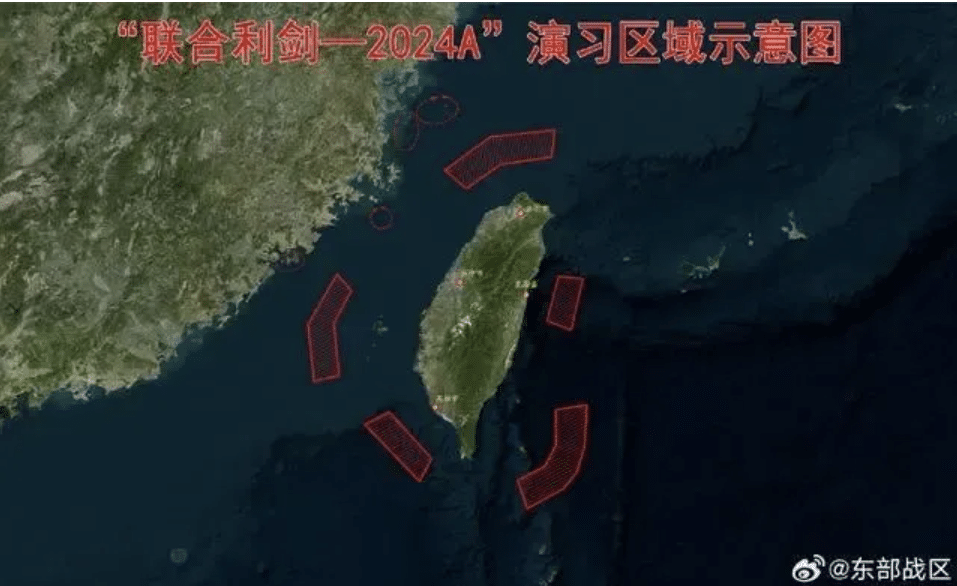

PLA Navy’s Three Carriers vs. U.S. Carriers in the Philippine Sea

The PLA Navy’s three aircraft carriers (yellow box) would likely operate about 1,000 kilometers from the mainland, while the U.S. Navy’s three carriers (green box) would sit roughly 1,000 kilometers east of Guam. The distance between the two carrier groups would also be around 1,000 kilometers.

Because land-based air support—primarily limited by fighter range—is essential, the PLA Navy’s carriers are best positioned about 1,000 kilometers offshore. Any farther, and they would struggle to receive meaningful support from land-based aviation.

At first glance, a three-on-three carrier matchup looks symmetrical. In reality, the PLA Navy faces several disadvantages.

- Carrier Capability Gaps

The Liaoning and Shandong clearly cannot match the performance of a Nimitz-class carrier. Even the Fujian—despite its advances—still lags behind the Nimitz and Ford classes in sortie-generation rates. This gap cannot be wished away.

The PLA Navy would have to maximize advantages in subsystems:

J-35 and J-15T carrier fighters, long-range air-to-air missiles, and airborne early-warning aircraft.

- Insufficient Flank Protection

The fleet’s northern flank would be harassed by aircraft and ships from mainland Japan. Its southern flank would be threatened by aircraft flying from the Philippines.

Given the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force’s current trajectory, it will likely field two carrier strike groups in a few years—both built around the Izumo-class helicopter carriers modified to operate a dozen or so F-35B fighters each. That is enough to provide top cover for Japanese submarines approaching the PLA fleet from the flanks or the rear.

Meanwhile, U.S. aircraft from the Philippines could also provide cover for U.S. submarines attacking from the south.

The Western Pacific is deep, ideal terrain for Japan’s quiet diesel-electric submarines. The PLA’s carriers would be forced to confront U.S. carriers head-on, with no spare airpower to protect the flanks. Those flanks would have to rely on destroyers, frigates, and submarines—along with land-based fighter cover.

Earlier estimates suggested the U.S. and Japan could field around 600 fighters from Japan, Guam, and the Philippines—airfields closer to the Philippine Sea than China’s east coast. From the Philippines, U.S. aircraft would need to fly only 600–700 kilometers to reach the PLA fleet.

PLA land-based fighters, by contrast, would have to fly at least 1,000 kilometers, consuming range and limiting time on station. To sustain continuous patrols and escort missions, the PLA would need a significantly larger force. Many aircraft would be tied up simply flying back and forth.

If the shaded areas represent zones of enemy submarine activity, any PLA anti-submarine aircraft or surface vessels heading outward would require fighter escorts—and that distance heavily strains fighter endurance. U.S. and Japanese fighters, operating from closer bases, could maintain patrols with fewer aircraft and much higher efficiency.

PLA submarines venturing outward would also be vulnerable to U.S. and Japanese anti-submarine aircraft—particularly those flying from the Philippines or Guam, both of which lie outside effective Chinese air interdiction.

- Vulnerable Rear Areas

Okinawa, Miyako, and other islands host numerous bases that would be saturated with anti-ship and air-defense systems during wartime. Taiwan’s own strike capabilities cannot be neutralized instantly either. These islands would impose constant pressure on PLA naval and air operations—including the movement of surface ships, supply vessels, and land-based aircraft attempting to support forces at sea.

If PLA strikes against these islands falter and fail to fully suppress their retaliatory capabilities, the PLA fleet operating in the Western Pacific could be surrounded and attacked from multiple directions.

Conversely, U.S. forces on Guam face much less risk. The PLA currently has only long-range missiles capable of striking Guam, and the volume of fire is inherently limited.

Airfields, in particular, are relatively easy to repair. How many missiles would the PLA need to prevent Guam’s and Tinian’s runways from supporting any takeoffs at all?

As long as those airfields remain functional, bombers and missile-launch platforms from Guam can continue providing support—likely more efficiently than the PLA’s own H-6K bombers.

Once inside the Western Pacific, the PLA Navy would essentially be operating in an encircled battlespace, with survival depending on maintaining an extremely high tempo of operations.

Overcoming These Three Disadvantages Requires Only One Thing: Mass

Three carriers are not enough. Even if the U.S. deploys only three carriers, the PLA must still account for Japanese naval aviation to the north and U.S. forces in the Philippines to the south. To absorb this much pressure, the PLA Navy would need at least five carriers, even under conservative assumptions.

More carriers would reduce dependence on land-based aviation and provide greater operational flexibility.

Second, land-based aviation must expand, especially long-range heavy fighters. H-6 bombers flying forward, or PLA anti-submarine aircraft pushing into contested waters, would all require fighter cover—and only heavy fighters have the range to do it.

As the J-35 enters service across the fleet, the J-20 could be freed for long-range maritime escort missions.

What About Missile Forces?

Some might wonder why the Rocket Force has not featured prominently in this discussion. The PLA fields a large number of hypersonic weapons at sea and a vast inventory of DF-series missiles on land.

However, space-based reconnaissance still cannot fully replace air-based reconnaissance. To exploit the full potential of hypersonic weapons, the PLA Air Force would need to secure airspace and provide real-time intelligence.

While carriers remain afloat, hypersonic missiles could be extremely effective. But once carriers are gone, relying solely on satellites and land-based aircraft makes it far harder to reliably track U.S. naval formations.

This brings us back to the central point:

A sufficient number of carriers and long-range fighters is essential to keep the Rocket Force, along with Type 055 and Type 052D destroyers, in the fight.

Missiles alone will not simplify war into a “just fire more ballistic missiles” equation.

Conclusion

If the United States and Japan were genuinely committed to military intervention, the impact on the PLA would be significant. At a minimum, China would be forced to divert enormous resources to counter their involvement.

The result would almost certainly be a mutually costly, high-attrition conflict.

Finally, this entire discussion omits one critical prerequisite:

How the PLA Navy, under wartime conditions, would break through the Bashi Channel and Miyako Strait—both of which would be heavily blockaded—and what price it would pay to pass through.