Interview with Zhou Wenxing: Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations in the Next Few Years—Is War Inevitable?

Interview With Amb. Daniel Kritenbrink on US-China Relations and Managing a Stable Competition

- Interviews

Tyler Quillen

Tyler Quillen- 10/29/2025

- 0

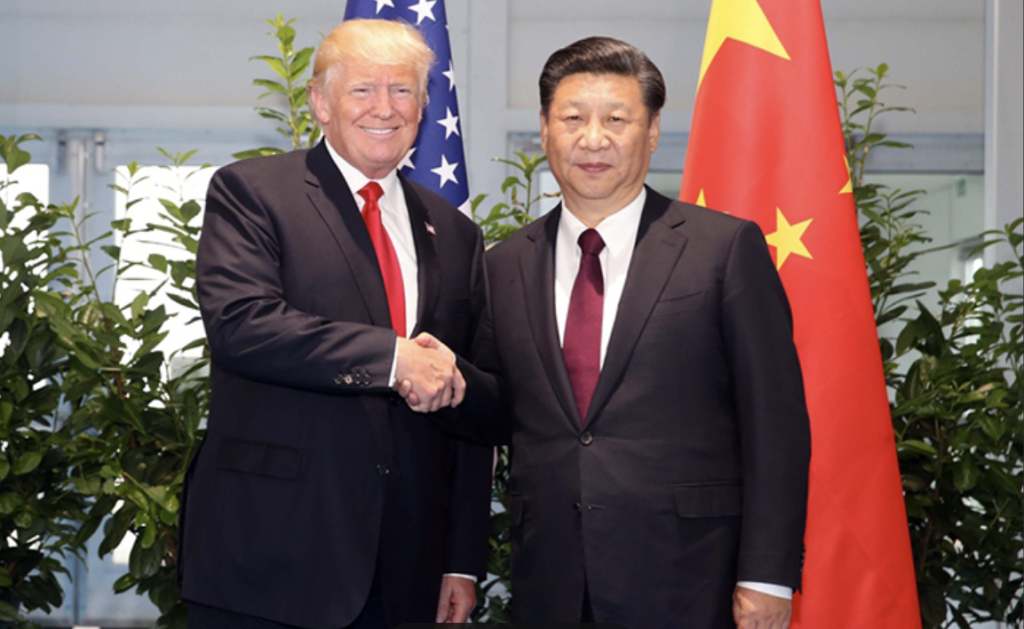

On July 8, 2017, President Xi Jinping met with President Donald Trump after the closing of the G20 Leaders’ Summit in Hamburg, Germany. Source.

The relationship between the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China, a bilateral relationship of great significance since its inception, has never been as important as it is today. Likewise, the management of diplomacy between the two nations is more vital than ever. The past decade, years, months, and even weeks have seen massively impactful shifts in relations between Washington and Beijing, capitals that now find themselves balancing their communications and actions on a knife’s edge on a daily basis. From trade negotiations, to Indo-Pacific security, to the Taiwan Strait and beyond, the world’s foremost superpowers have much to discuss and compete over, and the stakes surrounding such interactions have never been higher. To help unravel the diplomatic web laid out before us, The Monitor spoke with former U.S. ambassador Daniel Kritenbrink.

Mr. Kritenbrink has a deep history of experience in the world of American foreign policy and diplomacy regarding East Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Serving in a variety of Asia-focused roles within the U.S. State Department and National Security Council, his diplomatic career reached its heights with his time as the U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam under the first Trump administration, a position he continued into the Biden administration before becoming President Biden’s Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. Mr. Kritenbrink is now a partner at The Asia Group where he continues to lend his insights and experience to help manage American engagements in the region. Tyler Quillen sat down with Mr. Kritenbrink to apply those same insights and experience to understanding the modern U.S.-China relationship, what’s at stake in it, and what both government officials and private citizens can do to help manage the world’s most important bilateral relationship.

Tyler Quillen: How would you characterize the current U.S.-China relationship? How did we get here? And is this a new normal or a temporary departure from it?

Daniel Kritenbrink: Well, Tyler, great question. I would characterize the current U.S.-China relationship as being the world’s most consequential but most complex relationship. And I think that’s been the case for some time. And if you ask, how did we get here? I personally think one of the most significant global stories of certainly the last 50 years, particularly the last 30 years, has been the stunning rise of the P.R.C. in terms of its economic development, its political influence, the rapid development of its military, and the like. And I think it’s also well documented that from the very beginning there have been fundamental differences between the United States and China, including in our political systems, in our histories, our cultures, and our backgrounds. And yet, over this time, really starting from the opening that was driven first by President Nixon and then by President Carter, there was also an understanding that despite those fundamental differences, that the United States and China had certain fundamental interests in common. I think that’s what drove our cooperation for the first two to three decades of our relationship. And then, over the last 10 to 20 years, I think the differences have become more prominent. So, if you want me to give you a bottom line of where we sit today, I think the relationship has transitioned into more of a competitive one. My own personal view is that we should accept the competitive nature of our relationship, and we should embrace it. I think competition is healthy, but this is a challenging and potentially perilous moment as well. And so, we should do everything possible to manage that competition responsibly. And when you asked, is this a new normal or a temporary departure? No, I think this is the new normal—a highly competitive relationship between the United States and China is the new normal.

We can also talk about the specific details about where we are today under the Trump administration with the P.R.C. I would describe the current moment as, in President Trump’s second term, he has made trade and what he would describe as rebalancing America’s trading relationships around the world, one of his top priorities. I think the Trump administration and President Trump himself are trying to take a number of steps that they believe are either trying to reduce trade deficits or re-industrialize the United States by using tariffs and other tools to try to incentivize bringing supply chains back to the United States. That’s been generally the Trump administration’s approach globally. I think with China, though, the situation has been somewhat unique in that, apart from China, almost every country around the world adopted a relatively constructive and cooperative, maybe even conciliatory approach to negotiating with the Trump administration’s use of various forms of tariffs. Over the last several months, China took a very different approach. China took a mostly confrontational approach. If you talk to Chinese friends and officials, they would say the main lesson that they learned from the first Trump administration is that if you are hit or struck by the Trump administration in some way, you must strike back immediately. Tit for tat, eye for an eye. And I think Chinese friends believe that approach has worked fairly well for them. I’ve often said that my sense is that over the last few months we’ve fought this trade war in this first year of the Trump administration largely to a standstill. I think we’re in the midst of an uneasy truce. And now we see both sides trying to work toward a more stable U.S.-China relationship led mostly by diplomacy between the two presidents. Despite those best efforts, you can tell that this effort at stabilization is quite fragile. Just look at the turmoil and churn over the last few days following some steps that the U.S. took on the so-called 50% or Affiliates Rule regarding export controls. And then China has responded with this quite stunning global licensing regime for its rare earth exports. And that’s just the latest example, but I think that will be fairly typical going forward.

So, I’ve described here some of the details of what we’re seeing between the United States and China, especially on trade under the Trump administration, but that doesn’t change the larger dynamic I described a moment ago. The world’s most complex and consequential relationship is primarily competitive. Those are the fundamentals of the U.S.-China relationship that will, I think, further intensify that competition in the years ahead, and especially in the Trump administration I think there’ll be increasingly intense competition on trade. The thing that gives me some hope though, is that our channels of communication are open. Again, from Presidents Nixon and Carter on, I think leader-led diplomacy is what has largely driven and managed the U.S.-China relationship. My hope is that will remain the case under President Trump as well, and it looks like it probably will.

TQ: What are the root causes of mistrust on each side of the U.S.-China relationship? We’ve seen so much turmoil in the trade relationship, as you said, so what are the sources of that?

DK: The sources of mistrust are multiple and myriad. Obviously, if I were to take a step back and, from a scholarly perspective, try to be objective about this, you could say some of this might be inevitable. You’ve heard all the debates about the Thucydides Trap and the like; anytime you have an established power that is challenged by a rapidly rising power, there will inevitably be some suspicions and tensions. That’s one element, as I indicated. I think the fact that we have such vastly different political systems is another source of the mistrust. I had the privilege of living and working in China for eight years. I’ve spent really the last couple of decades working pretty intensively with Chinese counterparts. I would say as well there is—and again, as an American, I’m just trying to interpret what I have seen, heard, and felt from Chinese friends—I still think there’s a legacy of China’s so-called century of humiliation that still hangs over our relationship and really is kind of a weight that many Chinese friends and Chinese leaders carry with them. I still see and hear it via Chinese media, I hear it and see it from Chinese officials and from Chinese people, this continuing sense of grievance on the part of many Chinese friends and officials, that they’re aware of their history. They believe that somehow the West has tried to keep them down and now China is trying to establish itself as a great power and, as some Chinese friends would argue, take its more natural and rightful place on the world stage. So, I think that’s also one source of the mistrust. And I’m not necessarily saying that I’m embracing that view, I’m just saying that’s what I see, hear, and feel from Chinese friends.

Given the differences in our political systems, I think that’s a concern for many American officials, including many of our elected officials. And look, if I’m being very candid, I think it’s been stunning to see how much the U.S.-China relationship has changed in the last decade or two, and certainly over the course of my career. This is not designed to point fingers or assign blame necessarily, but I think if you look at that period, what has been the most dramatic change, it’s been China’s rise and it’s been how China has used that power and influence. I think probably the biggest source of alarm and concern, not just in the United States, but in many countries around the world, it’s been the fact that oftentimes the P.R.C. is willing to use many varied forms of coercion to try to advance their political and other objectives. And I think that’s also been a huge source of concern, certainly for the United States, but not just the United States.

TQ: Is the current administration’s China policy more strategic or more improvisational? What are the benefits and costs of inconsistency to the American public?

DK: Well, this is somewhat of a challenging answer. And again, I’m a retired diplomat. I’m now a partner at the Asia Group where we try to provide great strategic advice to our clients. So, I obviously can’t speak on behalf of the U.S. government and the Trump administration. But, as an observer from the outside and as a recently retired U.S. diplomat who served his country for 31 years, I would say that the Trump administration’s China policy feels more improvisational to me than strategic. But I can’t say that it’s entirely without strategic direction. Obviously, I mentioned at the top what the president said about what his objectives are. He’s talked repeatedly about the priority that he puts on reconfiguring the U.S. trading relationship with China. So, I think that’s his top strategic goal. I certainly hear that from other members of his cabinet, particularly Secretary Bessent, Ambassador Greer, and Secretary Lutnick. I would also say that if you look at some of what Secretary Rubio and Secretary Hegseth have said, I think they’ve probably taken a more traditional approach towards China across the region and have expressed concerns from a strategic perspective about certain Chinese actions. So, I think there is a general strategy, but I would still say it’s probably been more improvisational within a very general frame. Now, we’re still relatively early in the administration. To my knowledge, we’ve still not seen a formal speech on America’s China strategy, and we’ve not seen a written national security strategy or defense strategy yet from the administration. So perhaps the administration’s clear strategic goals will be clarified through such documents when they come out, but I would also say that in part, I think we’re also dealing with what President Trump considers one of his strengths, and that is being somewhat unpredictable and improvisational.

You asked here, what are some of the benefits and costs of that to the American public? In general, most businesses and investors crave consistency, predictability, and stability. And so, I think some of the churn that we’ve seen around America’s trade policies in particular have been unsettling for American businesses and investors. I think there are concerns over the inflationary impact of tariffs. And then, of course, if you if you look outside the United States, I think most of America’s partners and allies also crave consistency and predictability.

TQ: Thank you. Speaking of America’s partners, what do America’s partners make of the state of American diplomacy? How is the tenor of the current administration’s actions likely to influence nations caught between the U.S. and China, like Vietnam and the Philippines?

DK: You know, I had the honor of serving as America’s ambassador to Vietnam during the first Trump administration. So, I’m certainly quite familiar with how our Vietnamese friends view the Trump administration, and I have remained in close touch with partners across the region. It’s been interesting to see for most U.S. partners and allies, certainly in Asia, most of them felt like they dealt quite well with the first Trump administration. And I think the challenge for many of them has been in discovering that the playbook, so to speak, that they used with the first Trump administration is not entirely applicable to his second term. If I were to summarize this approach, I would say that in the second Trump administration, compared to the first, I think the president has put himself more front and center in every major decision related to U.S. foreign policy than compared to the first term. He’s assembled a cabinet that is more focused on being loyal to him and ensuring that he’s central to every decision that’s being made. And I think also the president has focused probably even more intently on trade in his second term and has been more willing to use various tools of force, including tariffs, in the second administration than he was in the first. In my experience in Vietnam, for example, I was usually using the threat of some kind of U.S. punitive action to try to compel partners to take various steps on trade. I think in the second administration the president’s preference has been to take significant action and then use negotiations over those steps and potential tariff relief as incentives for changing action. So, that’s been a challenge for America’s partners and allies to adjust to; many of them have, but that’ll be the challenge going forward.

You know, I mentioned a moment ago, most businesspeople in the United States and elsewhere crave consistency and predictability. And I think the same goes for America’s partners around the world. So, they’ve liked some of what they’ve seen, and they’ve been concerned by other U.S. policies, and probably more than anything, they’ve been somewhat unsettled by the unpredictable nature of some U.S. policies. But look, I would say that again, apart from China, I think almost every U.S. partner has taken a pretty constructive and cooperative approach to engaging the Trump administration. I do think that’s the smart move. I generally don’t see the world in complete binary and black and white terms. I don’t think our partners do either. So, I don’t really see partners running towards Beijing because they may have some frustration with the United States. What I hear from most allies and partners is that they want and need their continued strong partnership with the United States, and they’re working in the most constructive way possible with the Trump administration to bring that about and that includes the countries you mentioned here, Vietnam and the Philippines.

TQ: As a veteran of several government shutdowns, what does the current government shutdown mean for American diplomacy throughout the Indo-Pacific and the world at large? And moreover, how does a government shutdown, especially a long one, impact these nations’ view of the U.S.?

DK: You know, Tyler, I would say the impact in my mind is twofold. There’s the practical impact that when the U.S. government and U.S. government officials are not allowed to, on a daily basis, provide the services that they provide either to the American public or to foreign travelers who want to come to the United States. If we’re not fully staffed for our diplomats to seize opportunities overseas and to counter the threats that are clearly there and increasing, that concerns me. In other words, taking our eye off the ball at this perilous moment in international relations concerns me a great deal. And I think even though in every shutdown there are a number of employees who are excepted from any furlough and there will be a core crew who will continue to do the country’s business, I still hope this shutdown doesn’t go on very long because I think it does have practical and serious impacts on our ability to advance our interests and to protect them.

But I also worry a bit about the damage it does to America’s image. Part of our great influence in the region is our soft power and the faith and confidence that partners and publics overseas have in the United States, and any time when our own political polarization at home and disputes on Capitol Hill lead to something like this, I think it does undermine American soft power. So, I do hope that these differences can be resolved soon, at least to the point where the government can be fully reopened.

TQ: I very much agree. With a possible meeting between President Trump and President Xi approaching, what are the most important signals for the bilateral relationship that people should be looking for?

DK: Well, Tyler, as I mentioned a moment ago, I really think from the very beginning of the U.S.-China relationship, it’s been presidential-led diplomacy that has guided and managed the U.S.-China relationship, and I think that leader-led diplomacy has been quite successful. So, my hope will be that leader-led diplomacy will continue to drive the U.S.-China relationship under the Trump administration. I think the things we have to look for will be: will leader-led diplomacy impart the stability into the bilateral relationship that it traditionally has? I think it probably will, and I think that’s one of the main benefits of engagements between our two presidents. Secondly, when you have the leaders of two countries like the United States and China meet together, that provides leverage, and it also creates action-forcing events that allow the two countries to cut deals and to make compromises that they might otherwise normally not be able to do. That’s something we should look for as well. So, my hope is that you will see a diplomatic calendar unfold as President Trump had outlined following his most recent call with President Xi Jinping on September 19. He talked about having a meeting on the margins of APEC in Korea later this month, he then said he would plan to visit China in early 2026. And moreover, the hope and expectation was that President Xi would visit the United States at a future date, presumably for the G20, which will be held in the United States at the end of 2026. And of course, China will also be hosting APEC next year in late 2026. So, I think there are the prospects for a number of presidential engagements between the U.S. and China over the next year. I hope they happen because I do think they will help stabilize the relationship, and I do think they will create opportunities for outcomes, whether that’s commercial deals, agreements on various market access and other issues, potentially agreements on other issues including fentanyl, TikTok, and the like as well.

But we’ll have to see whether there’s enough stability in the relationship for those meetings to happen. I can certainly say on the Chinese side, my impression has been Chinese friends are normally reluctant to have their leader meet with the United States if there’s not a conducive atmosphere for such meetings. And so, sometimes it can be challenging for the leaders to meet when things are particularly tense. But look, given the challenges in the relationship, I think it’s more important than ever that our leaders stay in touch. I’ll also say though, as has hopefully been clear through my comments here, we should be realistic about what leader-led diplomacy can produce. I’ve mentioned here some of the benefits including stability and the possibility of deals, but as I stated in my first answer, the structural dynamics present between the United States and China will drive us towards greater competition and tension in the years ahead. I think that’s simply a fact, and I don’t think presidential diplomacy will change that. I do, however, think that leader-led diplomacy will be key to managing that and to making sure we do everything possible to prevent any kind of miscalculation that could lead to a crisis or conflict.

TQ: Yeah, absolutely. I’m going to be watching APEC with crossed fingers. As far as recent events in the relationship, how should we interpret the recent tightening of Chinese restrictions surrounding rare earth minerals? How impactful are they for the U.S.? And how do you expect this to affect Washington’s attitude and actions towards Beijing?

DK: Great question, Tyler. I think this is a hugely important matter that we’re dealing with right now. The actions that the Chinese have taken, I think they are in part designed to be a tit for tat response to steps the United States took. If you look at what Chinese officials have said publicly, they have complained that the United States took a number of steps just 10 days after the most recent phone call between President Trump and President Xi. Chinese friends were angered by this and have complained about it, saying that they were destabilizing and somehow running counter to what the two presidents had discussed and the meeting they agreed to have in Korea. So, the U.S. actions on export controls such as the 50% rule or Affiliates Rule expand pretty dramatically the application of various U.S. export controls for Chinese companies who are on the so-called entities list in the United States, and there were some other U.S. measures taken against Chinese shipping and the like. So, look, it’s partly a tit for tat response, but I also think given the really breathtaking scope of Chinese actions, it is broader than that. I think it also shows that China is trying to use its leverage and influence and its incredible control over much of the world’s production of rare earth minerals and rare earth magnets to increase its leverage not just against the United States, but vis-à-vis other countries around the world as well. And that’s where I think, whatever China’s intention was, they’ve overreached a bit here. So, I think that the U.S. public and Chinese friends as well should not underestimate this sense of alarm and anger that I’m hearing inside the U.S. government right now regarding these moves. And, if these Chinese measures were fully implemented to the letter of the law, these measures could be incredibly disruptive for global trade.

Now if I take at face value what Secretary Bessent and Ambassador Greer and others are saying, they’ve said that they’re optimistic that we have channels of communication with the Chinese side. We’re engaging very intently on these issues, and they’ve said they remain cautiously optimistic that they can be resolved. So, I’ll try to maintain that same sense of cautious optimism, but this is this is quite significant. So again, it’s partly a tit for tat measure, and it’s partly posturing and searching for leverage in advance of what we think will be the meeting between the two presidents. But it’s also a move with global significance. I think it does probably represent a bit of overreach on the part of the P.R.C. I think the issue of rare earths and the issue of China using various supply chains as coercive leverage for its political aims is a really significant issue that will complicate the U.S.-China relationship going forward, and it’s almost certainly going to have to be resolved if the U.S.-China relationship is going to become more stable.

TQ: You mentioned previously that you expect that just from structural effects the U.S.-China relationship to continue to grow more competitive, which I very much agree with. Based on your extensive diplomatic experience, what are the best ways that the two superpowers can manage tensions in their relationship? And are leaders in both capitals accomplishing this goal?

DK: It will probably come as no surprise to you, but I’m a former diplomat, I believe in talking to people. I believe in maintaining open channels of communication. And I fundamentally believe that diplomats from the United States and China need to be talking most and most candidly when things are most tense in the U.S.-China relationship. One of my fundamental worries about the U.S.-China relationship going forward is that, oftentimes in periods of tension or even crisis between the United States and China, Chinese friends will often restrict the channels of communication between the two sides, or sometimes they will go almost completely dark and there will be very little communication. I think that’s quite dangerous. So again, I think the best way to manage the tension is to always keep those channels of communication open. That’s no panacea. That’s no magic solution. But at a minimum, when things are so tense and when we’re facing a really consequential moment, there has to be the ability to clearly communicate with one another. And I would say I’m cautiously optimistic that as long as the two sides keep those channels open, we can at least prevent the worst-case outcome, which as I said, is a miscalculation that could lead to crisis or conflict, based on my own experience.

You would be surprised sometimes how the two sides can either misinterpret one another, or at least not completely understand how serious an issue is for one side. Or they may not completely understand the actions that one side may be contemplating taking in response to a serious matter. That’s where I think diplomacy is really important. And so again, the point this year where I was most concerned about the U.S.-China relationship was in the period immediately following the announcement of the so-called Liberation Day tariffs on April 2 by the United States when China responded in a very strong way. In the ensuing weeks, tariff levels reached really unprecedented levels of 145% and 125% respectively. We started squeezing one another in terms of various supply chain restrictions and the like, and we were barely talking to one another. I thought that was the most dangerous period that I saw this year.

The fact that we’ve had channels of communication since then has been key, but the U.S.-China relationship has to be managed not through diplomacy alone. I think if we’re going to maintain balance in this relationship, the United States has to focus on the sources of its own strength, both here at home and abroad, in terms of our domestic economy, our society, the strength of our military, and the like. So, I guess it’s an argument, yes, you need to have diplomacy, you need to have channels of communication. But I think the United States also needs to continue to focus on our sources of strength to maintain both balance in the relationship and a certain level of deterrence as well. And as a final point, I continue to believe that if one of our goals in this competition with China is to maintain peace and stability both in the Indo-Pacific region and around the world, I think U.S. diplomacy and cooperation with our allies and partners will remain fundamentally important as well.

TQ: Thank you. What are likely to be the most important inflection points for the U.S.-China relationship in the near- to mid-term future? What are the ways that these inflection points could play out?

DK: I’d say first and foremost in the near term is—and this probably would have been the case anyway, but it’s even more important given the focus of the Trump administration—I’d say the competition between both nations in terms of our trading relationship, our economic development, and especially our competition in various tech related sectors including AI. I think both countries see their success in the tech field as being most determinative to their future economic prosperity and security, and so that’s probably the most important issue in the near term. I don’t think we can take our eye off the ball, though, regarding some of the key strategic issues between the United States and China. Here I’m thinking about the cross-Strait situation related to Taiwan, other security matters related to the South China Sea, and potentially the situation on the Korean Peninsula, which given North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs, remains quite tense as well. As was the case in the diplomacy that first President Nixon and then President Carter engaged in and which allowed under President Carter our two countries to normalize our bilateral relationship, the issue of Taiwan was always central to U.S.-China relations, and it remains that way today. I think it remains the most significant and potentially the most dangerous issue between our two countries today. But I’m also confident that the wisdom of our forefathers that created this somewhat ambiguous but still mostly stable situation, continues to point the way forward. As well, I think that it’s incumbent upon all sides to recognize and support the cross-Strait status quo, and no power should be taking steps to undermine that cross-Strait status quo. So, I think we have to keep an eye on issues such as that going forward. But, in the near term, I think it’s going to be mostly about our trade and tech competition.

TQ: If relations between the U.S. and China continue to sour, what effect is this likely to have on civil society and businesses? What about the Asian American community?

DK: These are great questions, Tyler. I think one concern that I have about the intensifying competition between the United States is that the sense of competition and that growing sense of suspicion and even animosity can start to bleed into other parts of the relationship. And I think we’ve seen that some of that is natural, but some of that is also deeply concerning and even quite dangerous. If you look at the business community, it’s more complex. I mean one of the fundamental shifts in the U.S.-China relationship in the last 10 to 20 years, has been, I would argue, a change in the sentiment of the U.S. business community. And that is even though we still have a $700 billion bilateral trading relationship, and even though I think talk of decoupling is quite dangerous and destabilizing and not in the interest of either country given the level of economic interdependence that remains between us. There’s no doubt that a number of our leading American companies have fundamental concerns about the way they’ve been treated in in the Chinese market, the way they’ve been disadvantaged through Chinese policies and actions, and concerns about the distortionary nature of China’s mostly mercantilist economic development and trading model. So, tensions and concerns about trade and the fair treatment of U.S. businesses have been a core part of the relationship for a long time. We have to accept that, and I think China needs to do more to address those concerns. But I also hope that this intensifying competition doesn’t drive us towards a path of decoupling, because I think that that is not in either country’s interest.

Similarly, when it comes to our two countries’ civil societies and the relationship between our peoples, the fact that we have students studying in both countries, I hope that this intensifying competition does not affect that. It’s already had some effect, but I think it’s more important than ever that our two countries and two peoples understand one another, and you can’t do that if you don’t interact with one another. I can say from personal experience, the best way to facilitate that is to have our students studying in one another’s countries, and I hope that will continue going forward.

I also appreciate your question about the Asian-American community, including of course the Chinese-American community. I had an opportunity to discuss this with Representative Michelle Au at the at the great roundtable that you hosted at the Carter Center. I was really moved by what she had to say about how our fellow American citizens who are members of the Asian-American or Chinese-American community have felt about some of the developments of the last few years. I’ll make two points here. First of all, we have to make sure that, again, this intensifying competition between the United States and China never leads us as Americans to somehow view our fellow citizens with suspicion just based on their ethnicity or background, and we have to do everything possible through our actions and through our use of language to make sure that we stand up against any activities related to hate or discrimination directed at the Asian-American or Chinese-American community. That’s our fundamental responsibility as Americans, I believe.

But I’ll also add here, even though it’s not directly related to your question, but it is related to your question about civil society, I think it’s really important going forward that the American public, both private citizens and U.S. government officials, always have to distinguish between the Chinese government and the Chinese Communist Party on the one hand, and the Chinese people on the other. Through personal experience, I have tremendous respect and admiration and fondness for the Chinese people. I have met so many amazing people who I think share so much in common with Americans, and we need to make sure that we’re distinguishing between them and the policies of the government and the Chinese Communist Party that cause us concern.

TQ: Thank you, that’s fantastically put and a really important message to make. For my final question to wrap us up, what role can people outside of official diplomatic positions play in managing the relationship between the U.S. and the P.R.C.?

DK: Well, I think a pretty significant one. I personally have always believed that one of the foundational elements of any bilateral relationship that the United States has is the relationship between our two peoples. So, whether it’s businesspeople, tourists, students, I think we all have a role to play in ensuring that the competition between our two countries and governments doesn’t automatically bleed into animosity between our two peoples. And I know from personal experience how transformational and impactful study abroad can be. I had the experience of studying in Japan as an undergraduate, which was just a transformational, life-altering experience for me, all to the good. And so, I hope that we can continue to welcome Chinese students here in the United States. And you know, when I say welcome them, I mean certainly U.S. government policy has an impact there, but at the end of the day, it’s going to be how those students are treated and hosted at their home universities and in the in the communities in which they live that will dictate more than anything the image that people have of the United States. And I really hope we’ll see more Americans study in China as well; I know there have been some efforts to do that. I think we can all play a role in this by making sure we continue to live up to our values and continue to welcome foreign visitors and foreign students here in the United States. And, in that way, I think we all have a role in contributing to the U.S.-China relationship.

Author

-

Tyler Quillen is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and a graduate in International Security from the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Sam Nunn School of International Affairs.