Interview with Zhao Tong on the US-China Perception Gap

- Interviews

Tyler Quillen

Tyler Quillen- 10/08/2025

- 0

“The Dialogue Between Parents.” 1993. Mao Xuhui. Source.

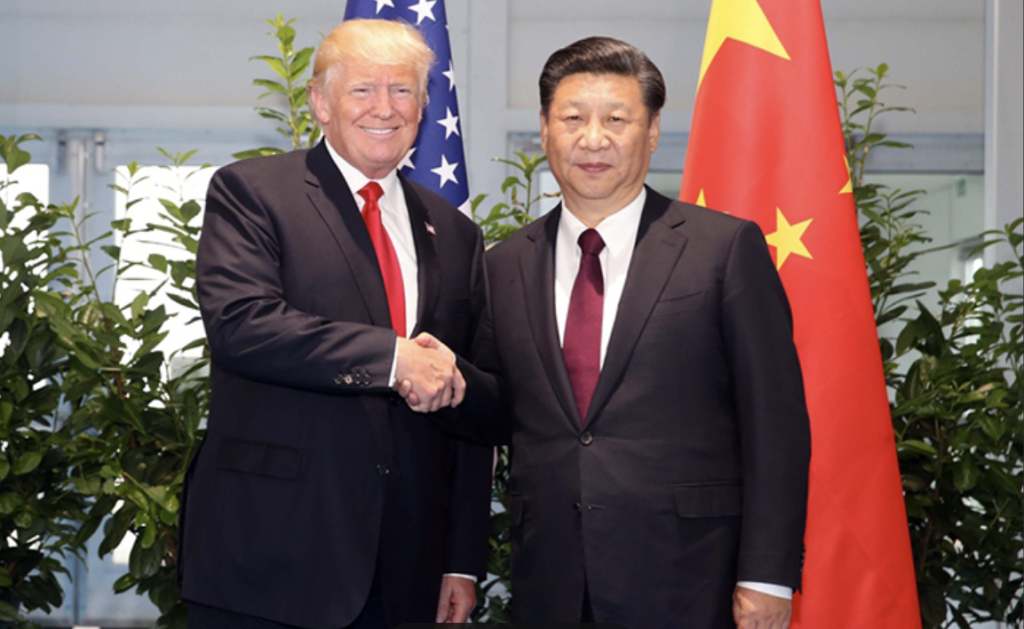

The world’s most important bilateral relationship, that of the United States and China, has been host to a veritable roller coaster of shifts in recent years and months. Changing and even contradictory policies from both Washington and Beijing have left the international community on edge as the two superpowers jockey for influence and a competitive edge. As misperceptions abound and the gap in capabilities across the Pacific narrows, the world is left to worry as to what comes next in this saga of great power competition. In a relationship fraught with so many moving parts, it is no small task to answer such a question. It is, however, not impossible.

The Monitor spoke with Dr. Tong Zhao to shed some light on the factors at play in this shifting relationship as well as what may come next. Zhao is a senior fellow with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace as well as a nonresident researcher at the Science and Global Security Program of Princeton University. Most recently, Zhao is the author of the article “Will China Escalate? Despite Short-Term Stability, the Risk of Military Crisis Is Rising.” Tyler Quillen sat down with him to discuss the sources of the shifts in the U.S.-China relationship and what they mean for the future.

Tyler Quillen: To start off, what are the most prevalent differences in perception of U.S.-China competition on the part of both countries? How do these differences in perception create danger? Which are the most dangerous?

Tong Zhao: For many decades, a major perception gap has separated the two sides. Over the past decade, U.S. threat perceptions have been driven by two factors: China’s growing power and—especially under Xi Jinping—its reversal of liberalization and deepening authoritarian turn. A China that is both stronger and less aligned with Western values inevitably heightens American concern.

Beijing’s reading is very different. China does not acknowledge its authoritarian shift; instead, a tightening domestic political climate has fostered a self-righteous narrative that Washington is the troublemaker—provoking tensions by criticizing China’s system, its handling of Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and Xi’s centralization of power. From Beijing’s perspective, the United States was pursuing regime change and threatening China’s core interests of regime security and legitimacy. The story Beijing tells itself is that U.S. hostility stems not from Chinese behavior but from anxiety over an impending power transition. In short, China attributes bilateral frictions to structural change in the balance of power—producing a fundamental perception gap.

The result is a dialogue of the deaf. One emblem of the bilateral gap over fundamental values is the four “red lines” Xi Jinping laid down last year: topics that are effectively off-limits in U.S.–China interactions. Two of the red lines concern regime security—human rights and democracy (which Beijing indicates should be excluded from bilateral engagement) and China’s political system (the CCP-led socialist order, which cannot be questioned). In recent years, Beijing had viewed the United States as posing an existential threat because it believed Washington was deliberately targeting its regime security—until Trump’s re-election.

As China’s ideology hardened and substantive bilateral exchanges grew harder, Washington became more alarmed by the destructive potential of a powerful China that no longer shares basic norms with the West. Confidence in diplomacy’s ability to bridge differences eroded. The prevailing U.S. interpretation increasingly cast China as intent on revising the liberal, rules-based order—spurring a popular view in Washington that the United States must prevent further Chinese power accumulation. Ironically, this reinforced Beijing’s long-standing conviction that containment is Washington’s goal, undertaken to preserve American primacy.

This dynamic has shifted slightly under the second Trump administration. President Trump prioritizes U.S. primacy and dismisses the democracy-versus-autocracy framing; he is less animated by China’s authoritarian character as a threat to the liberal West. That has modestly muted the ideological confrontation. Paradoxically, Trump’s weak commitment to democratic accountability and liberalism has somewhat stabilized the relationship and narrowed the perception gap’s immediate impact. Many Chinese strategists now worry less about the United States posing an existential threat. At the same time, they read Trump’s chaotic decision-making as accelerating America’s relative decline, bolstering Beijing’s confidence about its long-term position and further reducing its sense of existential peril from the United States. The gap persists—but, for now, it weighs slightly less heavily on the bilateral relationship.

TQ: To what extent does the current appearance of the U.S. retreat from the Pacific have to do with Chinese deterrence capability versus domestic U.S. politics?

TZ: Both developments matter, but the primary driver is domestic U.S. politics. China’s power growth is significant: its comprehensive national power—especially economic, technological, and military—continues to rise at impressive speed. Chinese high-tech firms have rolled out cutting-edge AI models; its biotech and pharmaceutical sectors look increasingly competitive; and Beijing has so far reduced the risk of a sudden bursting of the real-estate bubble, raising the odds of a soft landing. All of this reinforces China’s image as a fast-rising major power. In many domains its capabilities are seen as rapidly catching up with, and in some cases surpassing, those of the United States—enough to make an impression in parts of Washington and to contribute to President Trump’s growing hesitation to contemplate major conflict scenarios with China.

That said, U.S. domestic politics loom larger. Beijing sees U.S. decision-making as less cohesive and coherent under President Trump. He diverges from the Washington policy mainstream on the threats China poses, and because ideological differences matter little to him, he struggles to find a rationale for serious confrontation. He is also preoccupied with other regional crises and disputes—including with allies and friendly states—leaving it unclear whether his administration has a coherent China strategy.

This political indifference contrasts with operational focus. The Pentagon is reportedly trying to prioritize deterring the “pacing threat” from China. Yet even within the Pentagon there is debate over priorities: should the U.S. military focus on preventing a Chinese seizure of Taiwan, or on deterring Chinese military dominance in the Western Pacific regardless of Taiwan’s fate? A related question is how to reconcile this focus with Mr. Trump’s political indifference to the “China threat” narrative. Reporting suggests the National Defense Strategy under draft would put primary emphasis on defending U.S. interests in the Western Hemisphere, with countering China as a secondary priority—an approach that would have implications for U.S.’ global military resources allocation.

Senior-level communications have increased—between Dong Jun and Pete Hegseth, followed by a Wang Yi–Marco Rubio call—laying groundwork for leader-level engagements that appear preliminarily mapped over the next year: a meeting in South Korea in November, a potential Trump trip to China in early 2026, and then President Xi Jinping’s visit to the United States for the G20. Despite the lack of strategic clarity in Washington, I expect a near- to mid-term emphasis on managing high-level interactions. That focus itself can stabilize the relationship, as governments absorbed in preparing leader meetings have less appetite for major crises. For China, this is largely good news. Beijing likewise lacks a cohesive long-term U.S. strategy but is prioritizing near-term stabilization. As long as high-level engagement proceeds, Beijing likely believes it is buying time to build national power—on the view that, ultimately, the bilateral relationship will be shaped by the relative balance of power.

TQ: My follow-up question is, what do you believe are some of the root causes of the lack of cohesion in messaging and actions from Washington, specifically regarding the Pacific? Do you believe it stems more from a reaction to Chinese deterrence capabilities or more from domestic U.S. politics? To what degree do you believe this trend has reshaped Chinese perceptions of the U.S.-China relationship and how do you think Beijing is likely to respond if this trend continues?

TZ: The trend we’ve been discussing is driven primarily by domestic U.S. politics—a major source of the current administration’s incoherent decision-making at home and abroad. China’s growing deterrent is not the principal driver.

As for how this trend reshapes China’s perceptions and responses: when Beijing sees a U.S. system growing more chaotic, less coherent, and more deeply polarized, it has less incentive to engage substantively. Why place high hope in engagement if policy under the Trump administration can shift quickly and unpredictably?

Such volatility undermines the Trump administration’s capacity to sustain stable, long-term policies on key issues. Consider the widening gap between defense modernization and arms control: on one hand, President Trump appears committed to maintaining U.S. military primacy, including modernizing the nuclear triad; on the other, he periodically invokes the lofty goal of nuclear disarmament and speaks of denuclearization talks with Russia and China. Those are opposing signals. Heavy investment in nuclear modernization sits uneasily with proposals for denuclearization—or even limited arms-control talks—making the latter less credible in Beijing’s eyes. Even if the administration managed to articulate a more coherent approach to nuclear dialogue or defense relations, China would doubt its durability. If the president’s views shift frequently and the policies are increasingly contested at home, they risk reversal after the second Trump term ends. That perceived lack of predictability and sustainability further discourages Beijing from taking Trump-era proposals seriously.

Meanwhile, many in China judge that U.S. domestic disorder and policy incoherence are accelerating American decline—and that perception breeds confidence. A growing number of Chinese strategists argue that the relationship has entered a new era of “strategic stalemate”: where the United States once enjoyed clear coercive leverage, China now sees overall power nearing parity and U.S. leverage eroding. That rising confidence reduces Beijing’s willingness to respond to Trump initiatives it considers misaligned with China’s long-term interests. At the same time, continued tightening of domestic control constrains open debate within China, reinforcing the self-conviction that China’s current course is working. Despite acknowledged shortcomings of authoritarian governance, more Chinese experts now contend that, in broad terms, China’s system is outperforming ostensibly freer Western democracies marked by visible dysfunction in the United States and increasing turbulence in Western Europe.

If China grows more confident both in its material capabilities and in the supposed advantages of its political system, that bodes ill for long-term U.S.–China engagement. Even if a more conventional U.S. administration replaces the current one in four years, Beijing may by then have further hardened its domestic and foreign-policy posture—narrowing the window for constructive interaction.

TQ: In your article, you spoke about how the risk of armed conflict between Washington and Beijing rises as the capability gap between the two narrows. Could you please speak to what this narrowing of the capability gap looks like? How is China currently seeking to attain peer status with the United States and in what areas is the United States failing to upkeep its competitive advantage?

TZ: I think the capability gap—military and overall—between the two countries is shifting. This is especially evident in China’s ability to absorb U.S. technological innovations and scale them across industry, where it has shown a clear advantage. Beyond quick adaptation, China is also demonstrating growing capacity for independent innovation. Together, these trends are major drivers of the shifting bilateral balance of power.

On the military side, China is rapidly closing the conventional gap. If you watched China’s military parade in early September, Beijing unveiled entirely new platforms that surprised many long-time observers. In several areas, China appears to be moving faster than the United States. One example is its deployment of four distinct types of collaborative combat aircraft—”loyal wingmen”—a concept the U.S. pioneered but has struggled to achieve quick operational capability. By emulating U.S. ideas and leveraging its industrial scaling, China has fielded hardware that, in some respects, now outpaces the United States. Its edge in conventional precision missiles is also increasingly visible: the parade featured four types of anti-ship missiles spanning hypersonic gliders, hypersonic cruise missiles, supersonic cruise missiles, and aero-ballistic systems. Most recently, commercial satellite imagery suggests China has developed a much larger unmanned submarine platform, potentially capable of carrying more weapon types and performing a broader set of missions than current U.S. systems. This accelerating conventional build-up carries direct implications for Taiwan, the South China Sea, and the overall balance in the Western Pacific.

U.S. attention, meanwhile, appears to have gravitated toward China’s fast-expanding nuclear forces—an understandable response to Beijing’s rapid nuclear buildup and diversification. For the first time, the recent parade showcased a complete nuclear triad: land-, sea-, and air-based nuclear-capable systems. According to U.S. assessments, China’s arsenal has grown from a little over 200 warheads in 2019 to more than 600 by 2024, with projections of at least 1,000 by 2030. Even so, China’s priority appears to be conventional capabilities more than nuclear forces. I think conventional growth will prove more decisive in shifting the Western Pacific balance—and in shaping outcomes in any future crisis over Taiwan or the South China Sea—than the nuclear expansion currently commanding much of Washington’s attention.

TQ: In your Foreign Affairs article, you also touched on how China is taking advantage of the eroded relationships between the United States and its allies and partners in the Pacific region through a mixture of friendly economic and diplomatic outreach contrasted against aggressive military posturing. Could you expand on Beijing’s underlying logic behind this course of action, as well as how America’s partners are reacting to this combination of a more erratic and transactional Washington and an increasingly assertive China?

TZ: China holds significant misperceptions about the United States and its allies. Many Chinese strategists discount the agency of U.S. allies, seeing a U.S. “black hand” behind allied foreign and security policies. In Beijing’s view, Washington drives everything—so the United States becomes the natural focus of Chinese countermeasures. This tendency has intensified since Mr. Trump’s re-election, as America’s international image, credibility, and moral leadership have systematically declined under his administration. That creates added incentive for Beijing to target the United States itself: making Washington isolated and casting doubt on U.S. global leadership has become a priority of Chinese foreign policy. In parallel, China seeks to widen wedges between the United States and its allies by engaging those allies more proactively. We have seen visible efforts to mend ties with South Korea, Japan, Australia, Canada, and European partners: unilateral visa waivers for Japan and South Korea, reversal of earlier economic sanctions on Seoul and Canberra, and an uptick in bilateral—and even trilateral—high-level meetings. So far, this approach appears to be working.

At the same time, Beijing continues to wield pressure—implicitly or explicitly—against many of these same countries, including dispatching naval task groups as far as New Zealand and Australia earlier this year. Rather than a contradiction, this reflects a more confident Chinese doctrine. Beijing increasingly sees itself as a future global leader, approaching parity with—if not surpassing—the United States over the medium to long term. With that ambition comes a “principled” operating concept: reward cooperation, punish defiance. China is strengthening both levers—offering richer inducements to compliant states while imposing sharper costs on those that resist. The South China Sea illustrates the pattern. When Manila publicly challenges China, Beijing responds publicly and forcefully. By contrast, Vietnam’s lower-profile island expansion—arguably no less consequential for Chinese interests—has been downplayed because Hanoi maintains a deferential tone and stable bilateral ties. The result: more space for Vietnam to advance its aims, consistent with Beijing’s reward-and-punish logic.

U.S. allies would prefer to double down on cooperation with Washington to deter a more assertive China, but under Trump the United States looks less reliable. That leaves two imperfect options. First, build indigenous capacity: invest in strategic technologies—conventional missiles, hypersonic systems, air and missile defense—and, in South Korea, openly debate the need for indigenous nuclear deterrence. Second, tighten ally-to-ally collaboration: expand technology and defense links across the Atlantic and Asia. Examples include Japan’s next-generation fighter project with Italy and the U.K., growing Europe–Asia cooperation on cybersecurity, AI, and air/missile defense, including South Korea’s fast-deepening defense-industrial ties with Poland as a recent example. None of this will transform allied self-reliance overnight. Until those capabilities and networks mature, many U.S. partners will seek stable working relations with Beijing—meaning, in practice, selective accommodation of Chinese interests.

TQ: Speaking of America’s partners, your article made great points concerning Taiwan and its mounting plight of unification-seeking on the part of the PRC. You drew attention to several tactics, both military and otherwise, being employed by China in an attempt to induce Taiwan and its citizens to favor unification over a possibly worse alternative. Please speak some as to how effective these endeavors have been in terms of both Taiwan’s civil society and government as well as how this effectiveness or lack thereof impacts the likelihood of armed conflict.

TZ: Tensions over Taiwan are driven primarily by China’s internal political agenda. For Mr. Xi, the “Chinese dream” of national rejuvenation includes unification with Taiwan. For reasons of legacy—and if he seeks another term or continued influence—he may feel pressure to show progress on unification.

Beijing’s preference is “peaceful” unification, although “peaceful” does not mean voluntary. In practice it means avoiding open war, leaving wide space for coercion. The CCP has signaled its adoption of a comprehensive unification strategy in the “new era”; while its details are opaque, a central pillar appears to be shaping Taiwanese public opinion to believe there is no viable path to resist—neither through U.S. support nor through Taiwan’s own defenses. That entails systematic influence operations: cultivating local organizations, civil society groups, media, and opinion leaders to push narratives of U.S. unreliability and China’s irresistible power—framing acceptance of Beijing’s terms as the least-bad outcome. China has also worked to penetrate Taiwan’s military and political system—allegations include bribing serving officers to pledge loyalty in a crisis and recruiting collaborators across the Taiwanese bureaucracy to provide information and access.

At the same time, U.S. commitment to Taiwan appears to be eroding. Washington looks less willing to shed blood—let alone to risk nuclear escalation and a wider war—to defend the island. The international community is distracted by other crises and sees fewer stakes in Taiwan. Public sentiment in Taiwan shows growing pessimism about its ability to withstand Chinese pressure.

Even so, success is far from assured. Taipei is pushing back—most notably with the Lai Ching-te administration’s March rollout of 17 counter-infiltration measures. Beijing portrays such defenses as obstruction of unification and as justification for ratcheting up military pressure.

China has steadily intensified military operations and is tightening challenges to Taiwan’s effective control of surrounding air and sea space. If influence efforts fail to induce submission, Beijing will feel pressure to escalate coercion. The logic of “peaceful” unification is to instill sufficient fear to accept Chinese terms; if fear falls short, China must credibly signal real readiness to use force. The boundary between bluff and genuine willingness to initiate war is intentionally thin—and effective signaling requires real capability to win a war. Expect sustained military tension, with all the attendant risks.

There is also a persistent risk of Chinese escalation in response to what Beijing deems “provocations” by Taiwan (and the United States). In such a scenario, Chinese leaders may conclude that a sharp, demonstrative use of force is necessary to “teach a lesson” and deter future challenges. The result is a pathway with multiple decision points at which China could move militarily—not out of a desire to start an unprovoked war, but because it has convinced itself that mounting Taiwanese and U.S. actions have crossed an unacceptable threshold.

TQ: You also made a great point regarding the dangerously degenerative effect on America’s ability to meaningfully self-evaluate and bolster its military deterrence created by the push for loyalty above all else in the Trump administration. Could you expand on this concept and speak to how this influences the perceptions of nations like China, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan?

TZ: The United States’ capacity for meaningful self-evaluation is being eroded by declining democratic accountability and, at the operational level, by new incentive structures shaped by President Trump’s demands for absolute loyalty. The consequences are visible. Take his personal push for a nationwide “Golden Dome” to shield the homeland from all airborne and missile threats. In a more normal administration, such an ambitious military undertaking would face rigorous internal scrutiny—especially when U.S. economic competitiveness vis-à-vis China is uncertain. Effective deterrence requires rigorous prioritization; yet, I see no appetite of the current administration for broad, robust debate on the Golden Dome.

This pursuit is also crowding out other high-value defense needs, including nuclear modernization and, more importantly, stronger conventional deterrence. If China’s strategy over Taiwan and the South China Sea is to demonstrate decisive conventional superiority—and if the United States loses at the conventional level—the game is effectively over. Particularly as Washington’s political commitment to far-flung allies erodes, it is hard to imagine the United States credibly threatening nuclear escalation to compensate for conventional inferiority in conflicts it no longer views as high-stakes. Washington should be making careful, disciplined choices about where to invest; those debates simply are not happening in D.C.

U.S. signaling to allies is likewise erratic, breeding uncertainty. In Taiwan’s case, Deputy Defense Secretary Elbridge Colby previously urged defense spending at 5 percent of GDP; after President Trump expressed a preference for a higher figure, that call jumped to 10 percent—arguably necessary, but the haphazard process and messaging do little to bolster confidence in Taipei to work with the United States in achieving that goal. Allies will increasingly turn to indigenous capabilities, including more serious conversations about their own nuclear options. That avenue is not available to Taiwan.

There is a deeper, longer-term cost. As the U.S. system appears less democratically accountable—and more chaotic—Chinese liberals lose faith in the American model as an aspirational benchmark. Watching the United States veer toward instability and illiberalism, they grow disillusioned and more inclined to conclude that China’s own system “isn’t so bad” after all. That disillusionment weakens internal incentives to liberalize—further dimming the prospect of a democratic peace among leading powers and of a rules-based liberal order in the foreseeable future.

TQ: What would it take to reverse this trend of escalating tension between the two great powers? With the board as it stands, how could the United States effectively signal to China that escalation is not in its best interest, and vice versa?

TZ: Despite the perception gap we just discussed—and the resulting difficulty in meaningful communication—those deeper problems could become moot if a power transition proceeds, especially if the United States continues to decline and China continues to rise. In that scenario, some equilibrium could emerge: Washington would relinquish Taiwan and other regional commitments and further accommodate China’s ambitions and expanding interests. That is one pathway to stability. The alternative is sustained competition: the United States tries to preserve its global position while China falls short of rapid power transition. In that case, competition remains fierce and Beijing continues to seek unification through coercion, making the development of guardrails or safety net essential to buy time for an alternative, longer-term peaceful arrangement to take shape.

But managing the competition will require serious effort on both sides. Ideally, Washington and Beijing would stabilize the relationship by codifying basic principles of behavior; failing that, they should at least pursue concrete risk-reduction measures to address arms racing and the rising danger of military conflict and escalation. A major obstacle, however, is that they do not agree on who is generating the risk. They have yet to achieve a mutual acknowledgment of each other’s security concerns. China’s system struggles to recognize its own role in fueling tensions, and—as the U.S. system grows more illiberal—I worry that America’s capacity for self-reflection and self-evaluation is also eroding. As a result, I am not optimistic about their ability to effectively reduce the risks in the relationship.

Author

-

Tyler Quillen is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and a graduate in International Security from the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Sam Nunn School of International Affairs.