Interview with Zhou Wenxing: Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations in the Next Few Years—Is War Inevitable?

Wang Jisi: Has the Cold War Really Ended?

The Cold War came to an end in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the dramatic changes in Eastern Europe and the disintegration of the Soviet Union. More than 30 years have passed since then. The generation born after the Cold War has now reached their early thirties—a truly considerable span of time. Yet, from the perspective of global transformation and social development, 30 years is merely a blink of an eye. This is especially true for someone like me, who was born and grew up during the Cold War and is now engaged in international political research; it all still feels like yesterday.

The Cold War is Still Relevant Today

Why should we revisit the history of the Cold War? In reality, we are still living in a world structure shaped by that great Cold War era. Everything—from the strategic maneuvers between nations, the global governance system, the international financial system, trade rules, science and technology, and education, to ideological and cultural trends—down to our lifestyles, food, clothing, housing, transport, language, and artistic works—can trace its roots back to the Cold War era.

Take, for instance, our close neighbor, Afghanistan. The Soviet Union sent troops to occupy Afghanistan in 1979 and withdrew about 10 years later. The US sent troops to Afghanistan after the 9/11 incident in 2001 and also retreated ignominiously about 20 years later. Afghanistan has neither oil nor wealth, so why has it been subjected to intervention by major powers since ancient times, earning it the title “Graveyard of Empires”?

Another example is the many Chinese compatriots now engaged in construction and business in Africa. Africa was originally a colony of European powers, and the vast majority of African nations gained independence during the wave of national liberation movements in the Cold War period. Most African countries initially adopted multiparty parliamentary systems, modeled after their former colonial rulers. Later, some countries attempted to emulate the Soviet model and establish socialist systems. Without any understanding of this history, it is difficult to grasp the social situation in Africa today, and one may encounter unexpected problems when trying to start a business there.

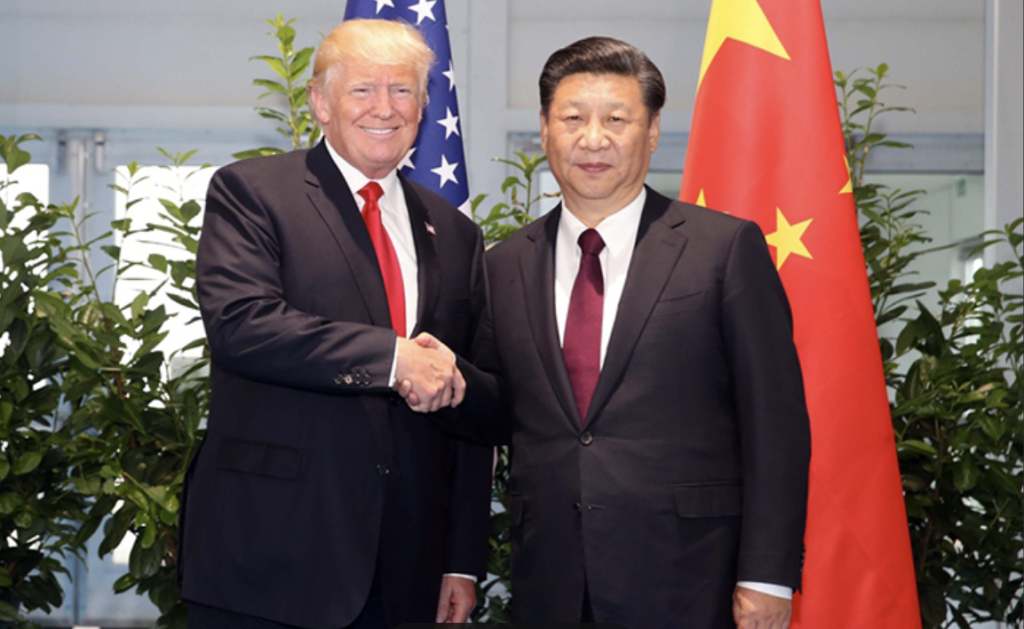

In recent years, China-US relations have faced severe challenges. The US has persistently adopted containment and suppressive measures, while China has countered based on reason, leading to numerous official-level disagreements. On the one hand, the worsening China-US relationship has affected non-governmental exchanges. Even without considering the disruption of the three-year COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people traveling and studying in each other’s countries has sharply declined. On the other hand, the escalation of strategic competition between China and the US, economic decoupling, and technological disengagement have affected the global political and economic landscape. Many people now believe that a bipolar pattern has re-emerged in the international arena, and a “New Cold War” has begun. Have China and the US entered a “New Cold War,” or are they on the verge of one?

I believe there’s no need to get tangled up in these questions or to confine oneself to a single historical concept. What is certain is that although the Cold War has ended, the logic of the Cold War has not disappeared. This logic will continue to shape the world’s landscape and our lives for a long time to come. Most of the state institutions and mechanisms that participated in Cold War decision-making are still operating, and many individuals who went through the Cold War process are still alive. The indelible mark the Cold War left on these institutions and individuals has yet to fade.

Understanding the Concept and Perspectives of the Cold War

In the context of international politics, the Cold War refers to the confrontation and struggle between the two major political blocs, led by the Soviet Union and the United States, from the mid-to-late 1940s to the late 1980s and early 1990s. These two blocs were also known as the Socialist Camp and the Capitalist Camp, or the East and the West. I have reservations about the concept of “East-West relations,” but I’ll use it here for the time being.

The confrontation and struggle during the Cold War had several key characteristics. The vast majority of countries in the world were drawn into it, though to varying degrees. The struggle covered every aspect, including ideology, politics, military affairs, economics, science and technology, culture, and lifestyle. The two opposing sides were largely cut off from one another, with very few economic ties and nearly non-existent civilian exchanges. While the two leading nations did not engage in direct warfare, localized and small-scale conflicts were constant. Large-scale wars like the Korean War and long-term wars like the Vietnam War also occurred, which is why we can say the “Cold War was not cold.”

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the specter of nuclear war that had hung over the world for nearly half a century vanished. This removed the biggest obstacle to economic globalization, making the world more peaceful, open, and prosperous. All constituent republics of the former Soviet Union gained independence, and apart from some Russians, few other nations seemed to regret the Soviet Union’s collapse. For China, the more than 30 years following the Cold War’s end have been an era of accelerated integration into the world and a significant rise in comprehensive national power and people’s living standards. Looking at it this way, couldn’t one argue that the Cold War’s outcome was good, or at least not bad?

Changing our perspective, can you imagine the Cold War not having ended to this day, or concluding with a Soviet victory and the defeat and disintegration of the United States? Is that an outcome we would have wanted? In terms of concepts and perspectives, another major issue is the relationship between whether a country is an enemy or a friend and whether it is a “good country” or a “bad country.”

In the early days of the Cold War, China joined the Socialist Camp led by the Soviet Union. At that time, we believed that socialist countries were all good, capitalist and imperialist countries were bad, and those that were neither were neutral. Another common line of thought is that countries with good official relations with China are naturally good, while those with poor official relations are, of course, bad. This mindset, a stereotype left over from the Cold War era, is still at play today. However, whether a country is an enemy or a friend, good or bad, is subject to change. The history of the Cold War offers the richest examples of this. Sometimes, objective circumstances necessitate the change, but more often, such shifts depend on a nation’s policy choices. I will frequently discuss this friend-to-enemy conversion in later chapters.

The shifting relationships between countries during the Cold War were not limited to China, of course. The two major powers, the US and the Soviet Union, actively cultivated proxies in many nations, leading to regime changes. For example, the US supported a right-wing military coup in Chile in 1973 that overthrew the socialist-leaning President Salvador Allende. The Soviet Union supported three coups by pro-Soviet forces in Afghanistan between 1973 and 1979 to depose leaders who did not follow Moscow’s directives.

The Logic of the Cold War: “Us” and “Them”

As I mentioned earlier, while the Cold War is over, the logic of the Cold War will continue to shape the world’s landscape and our lives for a long time. To understand what the Cold War’s logic is, we must return to the question of why the Cold War happened.

Why did the Cold War occur? I will elaborate on this in the first chapter. The most fundamental reason was the mutual fear between the free capitalist world led by the United States and the socialist world led by the Soviet Union and its Communist Parties, which triggered a state of absolute security anxiety. Both sides regarded the other as an inherent enemy, believing the struggle between imperialism and socialism was a life-and-death matter with no space for long-term peaceful coexistence. Both feared the boundless expansion of the other’s influence, believing that failure to stop it would ultimately lead to their own complete transformation and subjugation. This fear and anxiety differed from traditional great-power politics.

In traditional inter-state politics, opposing sides became enemies to compete for territory, resources, wealth, or labor, following the principle of the “survival of the fittest” or “two tigers cannot share one mountain.” In the political world before the Cold War, the antagonists were mostly “homogeneous states,” meaning their domestic political systems were largely similar, and the content and goals of their struggles were solely about “interests.” However, the opposing sides in the Cold War, in addition to conflicts of interest, also had conflicts of ideology and values, a contest over which political system was superior—an unprecedented struggle between “heterogeneous states.”

Ideology acted as a lens, capable of infinitely magnifying perceived interests. The US-Soviet rivalry was not just a struggle for national power and interests; it was a struggle over values and political systems. They were antagonists because “you are not only not me, but you are precisely my opposite; your purpose is to bury me, and my purpose is to bury you.” This antagonism was therefore more thorough and irreconcilable, persisting until Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, and the Soviet Union gradually showed weakness and finally conceded defeat.

Did this distinction between “you” and “I” end after the Cold War? Was the question of whether socialism or capitalism would prevail resolved?

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the renowned American political scientist Francis Fukuyama wrote a famous book, The End of History and the Last Man. Soon after, Fukuyama’s teacher, the even more famous political scientist Samuel Huntington, published another equally famous book, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.

Fukuyama expressed an optimistic belief that humanity’s main political conflict had been resolved—”liberal democracy” had triumphed over “totalitarian despotism”—and that things would likely “flatline,” remaining forever as they were. Huntington, however, pessimistically pointed out a new major conflict: the “Clash of Civilizations.” Over the past 30-plus years, facts have proven that history has not ended; the original major political conflicts continue, and new conflicts have emerged and intensified. The so-called Clash of Civilizations is significantly exemplified by the conflict between the Islamic and Christian worlds, as seen in the 9/11 incident. This conflict had already planted its roots during the Cold War but was merely overshadowed by the US-Soviet struggle for hegemony.

The history of people differentiating between “you” and “me” based on faith and ideas, leading to intense conflict and struggle, is more ancient than one might think. The conflict between Communism and liberal Capitalism is fundamentally also a clash of faiths. Today is often called the “Post-Cold War Era,” and in this time, the original, clearly defined “clash of ideologies” is, to some extent, being replaced by “identity politics.” The difference between “us” and “them” has shifted from socialist versus capitalist to distinctions of ethnicity, skin color, and cultural difference. Can we let go of this obsession with “either you or me, either this or that” and forge a new path of freedom, openness, and inclusivity?

The author, Wang Jisi, is a Professor at Peking University’s School of International Studies, the Founding Dean of the Peking University Institute of International Strategic Studies, a Peking University Boya Distinguished Professor Emeritus, and the Honorary President of the Chinese Association for American Studies. His latest book, Stories of the Cold War, was published this past April. The article was originally appeared at Sohu.com in Chinese.

Author

-

Wang Jisi is a Professor at Peking University's School of International Studies, the Founding Dean of the Peking University Institute of International Strategic Studies, a Peking University Boya Distinguished Professor Emeritus, and the Honorary President of the Chinese Association for American Studies.