Japan’s Prime Minister Takaichi Finally Says Something Close to What Beijing Wants to Hear

Stability Without Improvement: Professor Da Wei on the Risky Equilibrium of US-China Relations

- Interviews

Da Wei

Da Wei- 10/05/2025

- 0

Source: China-US Focus

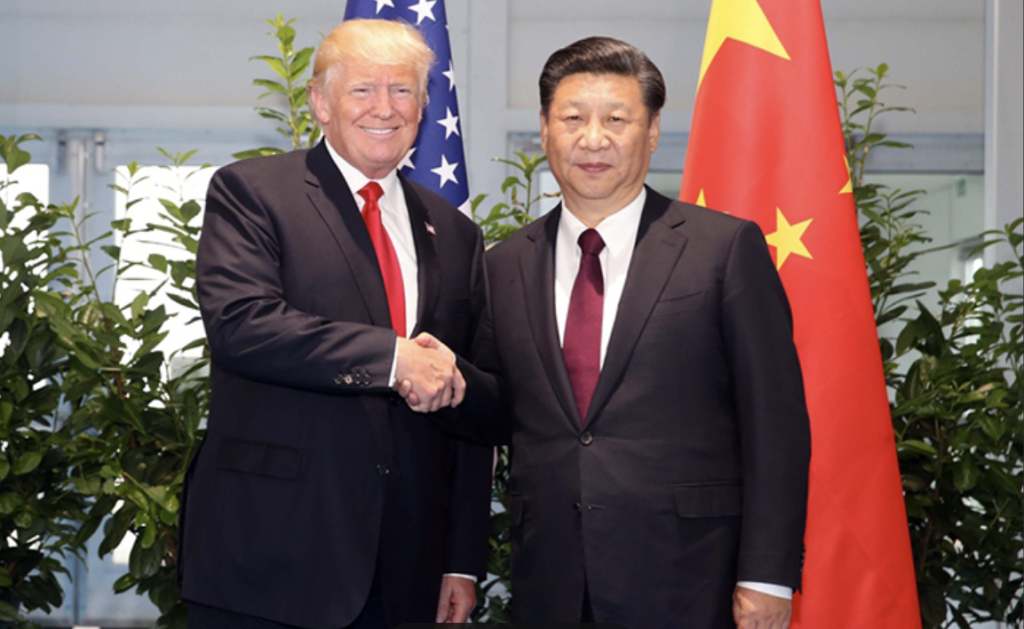

The 12th Beijing Xiangshan Forum was held at the Beijing International Conference Center from September 18 to 19. In a panel discussion on the opening day themed “The Trajectory of Major Power Relations,” Professor Da Wei of Tsinghua University’s School of Social Sciences observed that while China-U.S. relations have not visibly deteriorated in the short term, both sides lack strong incentives to improve ties. Still, both are focused on risk management, which leaves hope for relations to stabilize. However, he also noted that uncertainties remain, particularly regarding the impact of Trump 2.0 policies and technological advances on major-power relations. During the conference, Da Wei spoke with China-US Focus. Below are excerpts from the interview.

Q: Trump has been back in office for over 240 days. In these months, has there been any change in his China policy? What trends do you see? Compared with Trump’s first term (Trump 1.0), what are the differences?

Da Wei: The underlying policy logic between Trump’s first and second terms (Trump 2.0) may be consistent, but the way it manifests externally differs significantly. Trump 2.0’s China policy is, to a large extent, part of a broader adjustment of America’s overall foreign strategy—including both external economic and security relations. The Trump 2.0 administration is seeking to redefine America’s relationship with the outside world, not only with China, but also with Europe and other regions.

Since the end of the Cold War, under the backdrop of U.S. unipolar hegemony and the wave of neoliberal globalization, the United States developed a certain mode of relations with Europe, China, and other regions, such as the interdependence between China and the U.S. Now, America is revising this entire framework, largely because domestic opinion has concluded that the old model can no longer address pressing challenges such as the widening wealth gap. As this framework shifts or even collapses, the U.S. must correspondingly adjust its foreign relations—including with China, Europe, and Southeast Asia. The so-called “April 2 Liberation Day Tariffs” are a vivid example, reflecting a posture of “America versus the world,” not merely against China.

Comparing Trump 1.0 and 2.0: the former can be described as “one-on-one,” where the U.S. sought to suppress and contain China. Under Biden, it shifted to “many-on-one,” as the U.S. tried to rally allies against China. Now, Trump 2.0 has moved toward “one-on-many,” in which the U.S. is reshaping relations with the entire world. Of course, this does not mean it is “anti-world,” but discontent and suspicion toward the U.S. is now shared by many countries, not only China.

Thus, China-U.S. relations today are just one aspect of a larger shift. During Trump 1.0, China policy was arguably the centerpiece of U.S. foreign policy. Today, while still important, it is not necessarily the most urgent or top priority. Another difference is that, early in his second term, Trump—buoyed by his strong electoral win—believed that all countries feared the U.S., and that higher tariffs alone could force others, including China, to yield. Yet after grappling with multiple countries, and especially China, he gradually realized the limits of U.S. leverage.

In my view, since around May or June this year, while Trump’s China policy has not undergone a fundamental shift, tactically it has adjusted. The administration began seeking negotiations with China, recognizing that Beijing cannot be easily subdued and that dialogue is necessary. This explains why bilateral relations have gradually stabilized. Compared with Trump’s policies toward other countries, his approach toward China—though hardly friendly—has become less aggressive and more about coordination on an equal footing. The earlier condescending posture has been tempered by China’s firm countermeasures.

Q: Over the past 200-plus days, part of Trump’s policy adjustment stems from China’s countermeasures, such as Beijing’s restrictions on rare earth exports, which caught him and his team off guard. Beyond that and Trump’s own unpredictability, what internal team factors drove this shift?

Da Wei: U.S. Treasury Secretary Bessent may have played a crucial role. He is one of the more experienced, pragmatic, and sensible figures in Trump’s 2.0 team. When he realized that across-the-board high tariffs were unworkable, he managed to persuade Trump in a quiet and subtle way. After April 2, it was he who pushed to single out China while postponing tariffs on other countries. We of course oppose such measures, but tactically, there was some logic: the U.S. could not afford to fight on all fronts simultaneously, so it focused on China. Reportedly, this was Bessent’s idea.

Overall, Trump’s 2.0 “team” hardly qualifies as a true team. Unlike the 1.0 period, when there was a relatively strong and experienced bureaucratic apparatus, today the group is largely composed of loyalists whose main quality is obedience. Such figures are unlikely to provide substantive advice to Trump. People like Bessent are the exception, occasionally able to exert some influence.

Additionally, America’s economic outlook is worrying. The Federal Reserve just announced an interest rate cut, underscoring Trump’s concerns about the domestic economy. On the diplomatic front, he has run into major difficulties: after spending more than half a year trying to resolve the Russia-Ukraine conflict, he achieved nothing; in the Middle East, U.S. airstrikes on Iranian nuclear facilities and tacit support for Israeli strikes on Qatar have consumed significant attention. Against this backdrop, China is not at the top of his agenda.

Q: Politico recently reported that the new U.S. National Defense Strategy will downgrade China and Russia to secondary concerns, while prioritizing the Western Hemisphere and homeland security. If true, would this imply a shift away from the China-containment strategies seen under Biden and Trump 1.0?

Da Wei: The strategy has not yet been officially released. The mainstream view I hear is that the Politico report likely exaggerates. One possibility is that MAGA insiders, eager to cater to Trump’s preferences, drafted such language speculatively. But even if the final strategy says this, it may not be implemented. There is always a gap between strategy formulation and execution. In fact, any U.S. national security or defense strategy will declare the homeland and Western Hemisphere as top priorities—that is a universal principle of defense planning, working from near to far. If we saw the full draft, it would surely contain phrases like “U.S. security begins at home.” So Politico may have overstated things.

Q: How do you assess Trump 2.0’s Indo-Pacific strategy? Its momentum seems weak, with Trump still prioritizing trade wars. What direction do you think it will take? How about its key elements, such as U.S.-Japan-ROK cooperation, the Quad, and AUKUS? Will the Quad continue?

Da Wei: First, the Quad may continue, but its relevance to regional security will further decline. It has always been somewhat symbolic, unlike AUKUS, which involves tangible military technology cooperation (such as nuclear submarines). The Quad is more of a political gesture. I don’t think Trump cares much about allies, so neither AUKUS nor the Quad interests him greatly. Second, Trump dislikes wars. To him, these arrangements are costly, and cooperating with allies means spending money on them—something he resents. Third, the very existence of an Indo-Pacific strategy is in doubt. AUKUS may persist with some cooperation, but if that is the only framework left, the strategy becomes hollow. U.S.-India relations are currently poor; Biden’s Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) has stalled; Trump’s ties with Southeast Asia are strained; relations with India face setbacks. How can Washington push an Indo-Pacific strategy under these conditions? The name may remain, but in substance it is already hollowed out.

Q: Trump has expressed interest in meeting with Chinese leaders during APEC in South Korea. What outcomes do you expect from such a meeting?

Da Wei: Nothing has been officially announced yet, so we need to wait for confirmation. Generally, the two leaders might meet on the sidelines of APEC, though it would likely be a short meeting. According to Trump’s social media, he may visit China next year. In any case, there is a possibility of more high-level exchanges between the two countries in the coming period. I think tariffs will be a key issue: if they can be lowered or at least stabilized, that would be good news. Personally, I doubt U.S. tariffs on China will drop very far, but a deal could at least make tariff levels more predictable. In addition, both sides need to establish more frequent high-level dialogue mechanisms. That could be a concrete deliverable from a leaders’ meeting.

Q: Based on ongoing China-U.S. communications, how do you see Trump’s approach toward China in the run-up to the 2026 U.S. midterm elections? Over the next 18 to 24 months, do you foresee steady improvement or breakthroughs in the relationship?

Da Wei: The broad trend is likely to be one of stability, and it may remain stable even after the midterms. But I stress: stability is possible; genuine improvement will be very difficult.

Author

-

DA Wei is the Director of the Center for International Security and Strategy (CISS) and a Professor in the Department of International Relations at Tsinghua University.