Wu Xinbo: China’s Strength——The Key to U.S. De-escalation

- Interviews

Wu Xinbo

Wu Xinbo- 09/25/2025

- 0

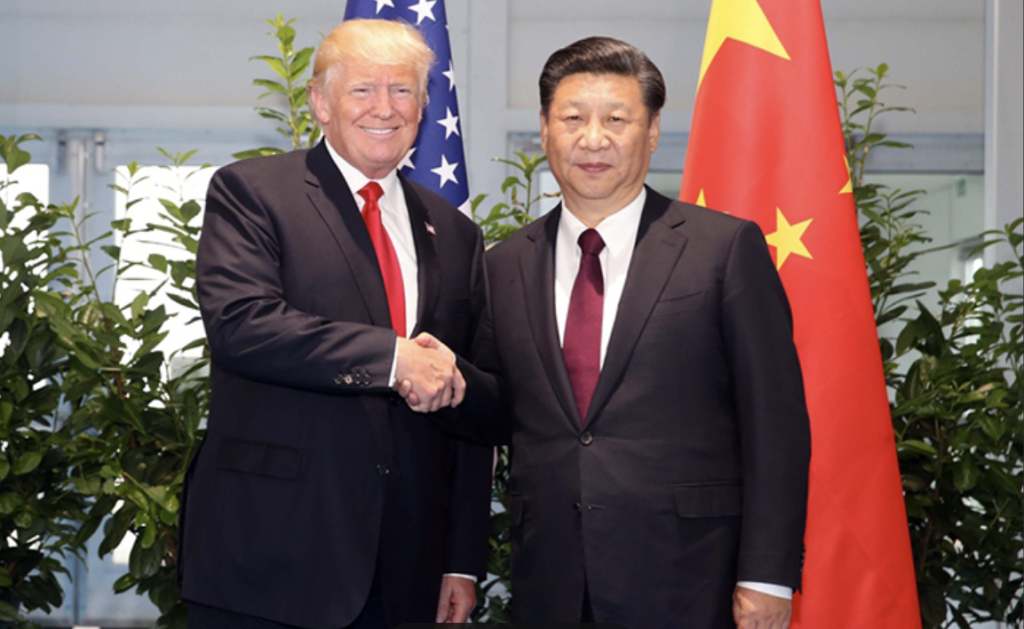

On September 14, 2025, representatives from China and the United States held trade talks in Madrid, Spain. Source

Editor’s Note: The closely watched Xiangshan Forum was held in Beijing from September 17 to 19. Since its founding in 2006, the forum has evolved from a “Track 2” exchange among international defense think tanks into a “Track 1.5” high-level dialogue between defense officials and scholars. According to China’s Ministry of Defense, this year’s event drew delegations from more than 100 countries, regions, and international organizations—including over 40 ministerial-level officials and military chiefs, as well as senior representatives from the United Nations and ASEAN. More than 1,800 participants registered in total. At the forum, Phoenix Net spoke with Professor Wu Xinbo, Director of the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University and head of its Center for American Studies. The conversation touched on U.S. politics and China-U.S. relations. Below is an excerpt focused on the latter.

Phoenix Net: Trump has said he does not want a potential war with China, yet he frequently intervenes in the Taiwan Strait, using it as a strategic bargaining chip. Is this inconsistency just a matter of strategic maneuvering? What changes in the Taiwan Strait situation during Trump’s presidency deserve attention?

Wu Xinbo: When Trump says he does not want conflict with China, I believe he means it. As a businessman, a clash with a major military power like China simply doesn’t add up.

But U.S. policy toward China—and especially Taiwan—has deep inertia. Washington has long played the “Taiwan card.” Whether under Trump, Biden, or George W. Bush, successive administrations have used it, believing it yields benefits: strategically or tactically constraining China, gaining leverage in negotiations, pushing Taiwan to buy American weapons, relocating TSMC to the U.S., and so forth.

The real issue is where to draw the line—whether such moves cross Beijing’s red lines and risk conflict. Neither the Biden administration nor the Trump administration has had a clear sense of this. Under Biden, for example, the Pelosi visit to Taiwan was a serious misstep.

If Trump’s administration now plays the “Taiwan card” during negotiations with China—by upgrading so-called “U.S.-Taiwan relations,” strengthening military ties, keeping American trainers in Taiwan, and deploying missile defense systems in the Philippines and Japan—then the red line is already being tested. This is dangerous territory. Under such conditions, tensions could escalate quickly, and friction would intensify.

So what should happen next? During Trump’s visit to China, Beijing should press Washington to halt all arms sales to Taiwan, demand a clear U.S. stance opposing “Taiwan independence,” and express support for peaceful reunification. China repeatedly pushed this during Biden’s presidency, but Washington did not comply—merely stating that it “does not support Taiwan independence,” while refusing to accept China’s position.

Now, with the Trump administration even removing the “not supporting Taiwan independence” wording from the State Department website, Beijing must seize every opportunity—especially during Trump’s visit—to apply pressure. On Taiwan, which is China’s core interest, the message must be firm: if Washington cannot deliver, it should not expect concessions from Beijing. Otherwise, the risk of conflict will grow. Trump must be warned, and if necessary, Beijing must act to make him understand the costs.

Phoenix Net: How do you view the outcome of the recent China-U.S. economic and trade talks in Madrid? Compared with “Trade War 1.0,” what stands out in the current phase of economic relations?

Wu Xinbo: Before Madrid, the two sides had already held three rounds of talks, mostly focused on tariffs. But this round went beyond tariffs, addressing issues like TikTok, U.S. tech restrictions on China, and the Entity List. The agenda expanded to cover investment, technology, and sanctions. This shows the two sides are starting to tackle a broader range of disputes—a positive sign.

Tariffs alone cannot define the economic relationship. There are many other issues that need resolution. For the next leaders’ summit, consensus must cover not just trade but also investment and technology. That is my key takeaway from the Madrid talks.

During Trump’s first term, tariffs escalated gradually—from $50 billion upward. Negotiations were drawn-out, culminating in the Phase One agreement. But that period saw a steady deterioration: tariff and trade wars, then tech wars targeting firms like ZTE and Huawei, then diplomatic clashes like consulate closures that spilled into cultural exchange. By the summer of 2020, the two countries had entered a strategic confrontation—a perilous point.

So Trump 1.0 was a story of “high start, low finish.” Within three months of taking office, he met with China’s president, but after his visit to Beijing, relations steadily declined, edging toward the cliff.

This time may be the opposite: “low start, high finish.” Early on, confrontation was fierce—launching the trade war—then came negotiations, and now talk of a leaders’ summit. In the short run, ties are on an upward trajectory. But beyond the next three years, it’s uncertain.

Trump faces two major events next year. First, the midterm elections. He must stabilize trade ties with China to ensure continued purchases of U.S. farm products, critical for votes in agricultural states. Second, the G20 summit. He needs China’s leader to attend; otherwise, the event risks falling flat. These factors make stabilizing relations a necessity.

If ties end this year on a positive note and remain steady next year, the outlook is relatively stable. But the two years after that are less predictable. Should Democrats win the House in the midterms and seek to undercut Trump, partisan battles would flare—and both sides would play the “China card.”

Add to that America’s sluggish economy, a tendency to blame external factors, and the approach of the 2028 presidential election—combined with Trump’s mercurial style and potential third-party surprises—and the longer-term trajectory of China-U.S. relations is hard to forecast.

Phoenix Net: How do you see China-U.S. relations developing from here?

Wu Xinbo: I frame it in terms of the “big trend” and “small cycles.”

The big trend is clear: the U.S. sees China as its main strategic competitor. Washington believes only China has both the ability and the will to challenge its dominance. Thus, it engages in so-called “strategic competition”—in essence, containment and suppression. This trajectory is long-term and bipartisan. In recent years, both Democrats and Republicans have moved in this direction, and it won’t change in the near term.

But within this big trend, there are small cycles. During Biden’s later two years, domestic politics and diplomacy—the APEC summit, election-year needs, economic pressures—pushed him to seek a degree of easing with China. Competition was still sharp, but relations softened temporarily.

With Trump, we’re seeing the same. At first, his approach was aggressive—slapping 145% tariffs in an attempt to quickly force concessions. When that failed, he pivoted to talks and a potential new deal. So for now, relations look to be improving. But this won’t last. For political and strategic reasons, the U.S. will eventually ramp up pressure again. This easing cycle may last a year, two at most, before rivalry resumes. That is the pattern of the relationship today.

Phoenix Net: You’ve said before that “China and the U.S. are not destined to be adversaries.” Looking long term, what opportunities or turning points might ease bilateral tensions?

Wu Xinbo: In the long run, everything depends on China’s development. When China’s economy surpasses America’s in size, when it breaks through in key technologies like semiconductors and lithography machines—then, whether Washington likes it or not, it will have to face reality: decades of competition and containment will have failed. At that point, the U.S. will have to adjust.

Consider history: after the World War II, the U.S. contained China for 20 years. When that failed, Nixon opened the door, transforming U.S. policy. Something similar could happen again. The U.S. might come to see China not only as a rival but as an indispensable partner—economically and diplomatically—in achieving its own goals. That would be the opening for substantive improvement in relations.

In the decades after Nixon’s visit, cooperation outweighed confrontation. The U.S. regarded China as both partner and rival, but primarily as a partner. History often moves in cycles. At some stage, the U.S. will again see China as a critical economic competitor and partner—needing its markets, investments, technologies such as clean energy, and key supply chains.

We’ve seen this dynamic before. During the 2008 financial crisis, the Bush administration found little help from the G7. Only China had the capacity to contribute. The U.S. turned to the G20, brought China in, and sought greater cooperation.

So, in the long run, this day will come. But it won’t come from American goodwill alone. It requires China’s own progress and strength to create a new reality that forces Washington to adjust. International politics is shaped by power, and Americans are especially pragmatic. Unless China’s capabilities reach a certain level, the U.S. will not treat it beyond that level.

There must also be a reckoning inside the U.S.—a recognition that the policies pursued since Trump’s first term have failed, cannot succeed, and ultimately harm U.S. interests. Only with such a pragmatic adjustment will a new chapter in China-U.S. relations open.

Author

-

Wu Xinbo is a professor, director of the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University and head of its Center for American Studies.