How Capable Are the U.S. and Japan of Intervening in a Taiwan Conflict?

China, India, and the United States in a Multipolar World

- Analysis

Yasser Ali Nasser

Yasser Ali Nasser- 09/06/2025

- 0

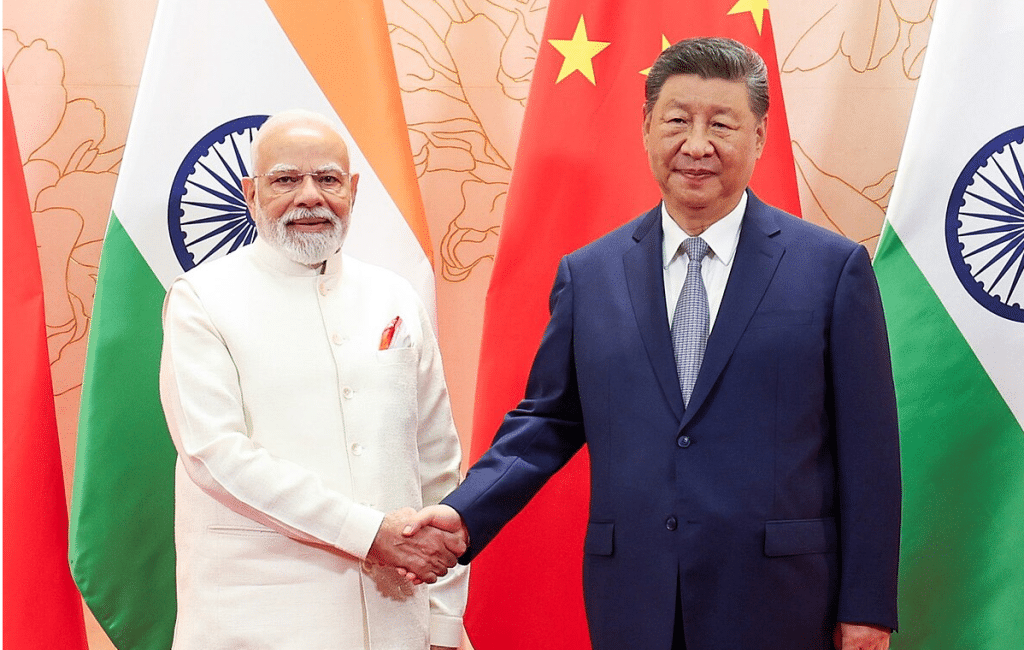

Prime Minister Modi with President Xi, August 31, 2025. Source.

The Sino-Indian relationship has long been a perplexing one. Since Indian independence in 1947 and the formation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) with ‘liberation’ in 1949, the two countries have drifted through various brief phases of warm and friendly relations punctuated by lengthier periods of indifference at best and hostility and suspicion at worst. The new millennium, however, seemed to promise a new era. Economic cooperation and trade began to increase dramatically, capped off in 2010 by a visit by Wen Jiabao, then-Premier of China, along with 400 senior business leaders to India. Though the border periodically cropped up in issues, especially as India pushed its claims in the disputed state of Arunachal Pradesh, Party General Secretary and President Hu Jintao and then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh committed in 2012 to developing friendship and seeking “common development.” The two sides also signed limited agreements in an attempt to defuse border tensions.

The first years after Narendra Modi’s election as Prime Minister did not seem to change this trajectory much. When Deng Xiaoping met with Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, the grandson of Nehru, in 1988, he argued that the 21st century was bound to be an “Asian Century” – dependent, ultimately, on India and China becoming developed and advanced economies. Certainly, Asia’s economic rise seems to suggest that Deng was correct. When Xi Jinping visited India in late 2014 as one of the first major world leaders to be feted by Modi, the Chinese Premier reiterated these same sentiments.

The joint statement that he and Modi issued argued that “simultaneous re-emergence of India and China as two major powers in the region and the world offers a momentous opportunity for realisation of the Asian Century” and that both countries were bound to “play a defining role in the 21st Century in Asia and indeed, globally”. Their relationship thus necessarily had to be a constructive one, bound by mutual respect, and with a desire to provide “a new basis for pursuing state-to-state relations to strengthen the international system.”

New tensions around the border, however, erupted by 2019 and dampened the relationship significantly, though there have been signs over the last year that the two countries are working to undo this. Regardless, Indian popular surveys, politicians’ statements, and military personnel’s own commentary would suggest that even as Pakistan remains one of India’s major geopolitical rivals, China is seen as a much more challenging threat to the country’s security interests.

In recent months, with the threat of Trump’s tariffs looming over both countries, Indian and Chinese diplomats and statesmen have signaled the need for rapprochement. Only about ten days ago, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited New Delhi to meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi and other senior Indian officials as direct flights between the neighboring nations are set to resume for the first time in five years, and the border issue has again been taken up by both sides. As Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in a meeting with his Indian counterpart S. Jaishankar, the two countries should view each other as ‘partners’ rather than ‘adversaries’.

It is hard to say where all of this rhetoric will necessarily lead. Political science scholarship on India from Chinese scholars has generally had a relatively dour attitude towards Indian economic growth, rightly noting that the Indian economy and Indian society suffers from certain imbalances that make sustained economic growth and the distribution of those gains across a wider spectrum of the population relatively difficult. These include: a lack of nationwide land reform, rural poverty and debt, collusion between political and financial elites, and the monopolization of whole industries by a select few powerful conglomerates. There is little doubt today that China has become the premier economic power of the Asia-Pacific, making up nearly half of the continent’s GDP; India, on the other hand, makes up less than 10%, just behind Japan.

Despite this, in the last few years, popular Chinese narratives about India’s potential as a major power in Asia have begun to shift. When India overtook China to become the world’s most populous country in 2023, netizens on Chinese social media responded with a relatively gloomy outlook: India, as a younger and more populous country, would have more economic and thus geopolitical importance and potential as time went on, whereas China’s aging population and slowing economic growth would endanger its capacity for regional leadership. As tensions with China have risen in other Asian countries, likewise, there has been a turn towards India as a potential counterweight to Chinese influence, especially as the country has begun attracting much of the foreign capital and investment that had once found its way to China’s special economic zones.

It is hard to say whether or not such a forecast would ever come true. India’s economic growth has been uneven and inconsistent over the last decade; the country likewise remains somewhat difficult to do business in compared to other would-be successors to foreign investors in China, such as Vietnam and Bangladesh. But these anxieties reflect general fears that India, as a country where relations with China have been complex and strained despite certain shared interests, may drift closer towards the United States and continue the general trend of broader Asian antipathy towards China. This is complicated by the Trump presidency.

The majority of political commentary from Chinese political scientists and international relations scholars would suggest that the inclusion of India in the Quad and growing American military cooperation with the Indian armed forces is a sign of the United States’ growing desire to bolster its position in Asia. The Quad is seen as an attempt to promote the ‘NATO-ization’ of the Asia-Pacific region, with countries like India, Japan, and South Korea serving as key pillars in the U.S. alliance system. This is generally in-line with much commentary on American relations with India over the last several years: India is being used, ultimately, as a tool in larger American machinations in the region, much in the way that the United States once used countries in SEATO and other treaty organizations during the Cold War.

Key here is an emphasis on naval power and cooperation. Traditionally, as many authors note, the Indian armed forces have generally focused on the modernization and funding of India’s army as well as air force in a bid to compete with Pakistan as well as China. The United States’ concerns in Asia are generally maritime, however: maintaining navigability across the Pacific and Indian Oceans as well as the South China Sea to keep trade flowing and to thwart the potential of a Chinese attack on Taiwan or other allies in Southeast Asia. Australia and Japan have likewise begun to place more of an emphasis on naval power in anticipation of an American pivot to the region. Unlike NATO, then, the potential of military cooperation within the framework of the Quad relies chiefly on the expansion and maintenance of naval power and strategic cooperation. As a report from Xinhua on American plans to establish military facilities in India put it, Indian shipyards have chosen to begun cooperating with the U.S. military to provide crucial supply and maintenance services in South Asia in exchange for aid in building and supplying the Indian Navy’s own naval and aerial capabilities.

The inclusion of India, a traditionally neutral country and one without a history of deference to American geopolitical aims, would also likely in time make the Quad format an attractive one to other countries skeptical of Chinese geopolitical aims in the region, such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. By focusing less on a traditional military alliance system and more on infrastructural construction, joint patrols of the South China sea, and intelligence sharing, and encouraging Japan, Australia, and India to pursue their own partnerships on their own terms, scholars warn that India’s participation in the Quad makes it clear that the United States is attempting to build a system designed to not just “check” China’s military rise, but also to prevent China from expanding its influence in the Indo-Pacific region

Still, most Chinese commentators on the Quad and American relations with India more generally: this is a marriage of convenience, not ideals. Often invoked is the fact that up until the revival of the Quad, the United States had maintained some skepticism towards the Modi government due to its treatment of religious minorities, particularly under President Barack Obama. As Xie Chao 谢超, an associate researcher at Fudan University’s Centre for South Asia Studies argued in a recent article, the price for Modi’s involvement in the Quad had essentially been the United States suppressing its concerns about India’s human rights issues in a move that Chinese media has often derided as hypocritical and clearly in tension with American declarations of a ‘democratic’ alliance against Chinese ‘authoritarianism’. Towards the tail-end of the Biden administration, tensions over support for Ukraine again came to the forefront and, as Xie notes, this coupled with Modi’s intensified suppression of political opposition led to growing American criticism of Indian human rights and faltering democratic values. Xie notes these contradictions to be a major reason why the upward momentum of U.S.-India relations is “no longer sustainable and is returning to the traditional path of competition and cooperation”

Today, despite American protests and sanctions, India continues to purchase Russian energy and arms in large quantities. The Modi government has largely ignored American calls to join the sanctions efforts against Russia; Chinese media has likewise reported favorably on India’s resistance to damaging its relations with the country as proof that “no matter how close India and the United States are, India is still an independent international political player, and is by no means a small follower and vassal of the United States.” These tensions have been coming to the fore more often following the start of Trump’s second presidency. Despite a personally good relationship between Trump and Modi, the former’s disparaging of India as a “tariff abuser” and recent imposition of harsh tariffs on a country seen as crucial to weaning American businesses off of investment in Chinese industries and special economic zones have no doubt damaged the relationship further.

This relatively sanguine outlook on U.S.-India relations notwithstanding, Chinese commentators on Indian politics have nonetheless commented on the relative adroitness of the Indian government in international politics. Despite its gravitation towards Russia for energy and increasing reliance on the United States for trade and arms, India remains seen both by its own public and on the international stage as a strategically independent and neutral country, retaining its traditional commitments to an autonomous foreign policy which steers clear of overt alignment with any one geopolitical camp.

As Mao Keji 毛克疾, an upcoming research analyst at the National Development and Reform Commission and an expert on Indian politics, has suggested in a recent interview, while India has “sought to leverage its future great-power status and its strategic potential to counterbalance China in exchange for free strategic resources”, Trump’s desire to impose a cost for such resources and collaboration would likely lead to more friction with the Indian government overtime due to pressure on Modi to avoid “aligning too closely with the US at the cost of India’s strategic autonomy.” In Mao’s estimation, this leaves an opening for a thaw in Sino-Indian relations, precisely because “even if India is not genuinely friendly towards China, the mere facade of Sino-Indian friendship could help India increase its value in the eyes of the US.” In other words, if India’s value to the United States stems from its potential as a partner in the quest to contain China, then an Indian overture towards China might force the United States to prioritize the relationship and make key concessions to India.

Despite competing interests in their outreach towards the Global South, which both countries have historically seen themselves as the leader of, both the Indian and Chinese publics largely believe that more economic and political importance will shift to the developing world as the 21st century progresses. What Chinese commentators have more recently argued is that this is precisely why India should avoid competing with China as opposed to working with it. And there are signs of a thaw.

Though tensions over visas and diplomatic appointments remain, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between India and the PRC on April 1st of this year, Chinese Ambassador to India Xu Feihong 徐飞洪 gave a detailed interview for China Daily and Global Times in which he argued that both countries were “two important forces in the process of world multipolarization, the vital force driving world economic growth, and the leading force of the countries of the Global South, China and India have once again been pushed to the forefront of the times.” Xu noted that Modi himself has argued of late that India and China have shared global interests and that despite their differences, the relationship has room to improve, develop, and become mutually beneficial.

Likewise, in an interview for China Times marking the same anniversary, Indian politician and member of former Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s cabinet Sudheendra Kulkarni argued that if China and India could dispel each other’s security concerns, they could “cooperate with other major powers in the region to ensure that Asian security is jointly maintained by the Asian people and free from destructive external interference.” This not-so-subtle reference to the United States and the Quad – and to older Sino-Indian rhetoric on the need to prevent “Asians from fighting Asians” during the Cold War – would suggest that there are at least some Indian political actors willing to countenance a closer relationship with China in order to cement the country’s regional prestige and importance. This would, as Kulkarni himself emphasized, require significant concessions from both sides on the border question. Whether the Indian or Chinese publics would accept such concessions, however, is another story.

Author

-

Yasser Ali Nasser is an Assistant Professor in the History Department at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His work explores the intersections between nationalist and internationalist impulses in East and South Asia.