Interview with Zhou Wenxing: Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations in the Next Few Years—Is War Inevitable?

Engagement is Not Dead w/ Terry Lautz and Deborah Davis

- Interviews

Miranda Wilson

Miranda Wilson- 08/23/2025

- 0

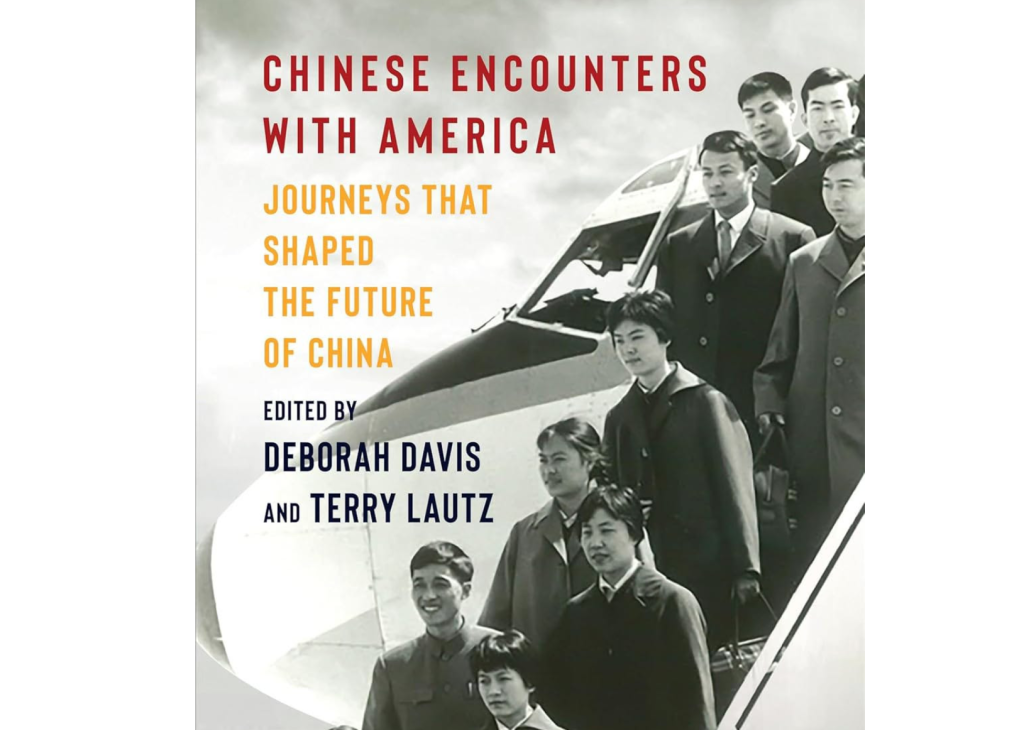

In December of 2024, I had the opportunity to interview Terry Lautz about his book Americans in China (2022), which details the lives of 13 Americans who spent time living in China. Six months later, I sat down with Lautz and Deborah Davis to discuss their newest project, Chinese Encounters with America, which tackles the inverse prompt: influential Chinese people who spent time in America. Lautz and Davis co-edited the book, which features 12 portraits of Chinese people in America, authored by many big names in the field of China studies, including Davis herself. Davis’s chapter covers the life of Xie Xide, a Chinese physicist who studied in the United States and whom Davis shares details of in this interview. The book is bracketed by a relevant and thought-provoking introduction and conclusion written by Lautz, which we also discuss in this interview.

Chinese Encounters with America, like Americans in China, serves as an important reminder that “engagement is not dead,” as Lautz so importantly states. People-to-people connections are a defining part of U.S.-China relations, and the people highlighted in this book highlight the shared values, friendships, and cooperation that are possible between our two nations.

On August 28, in partnership with the Chinese Center at the San Francisco Public Library, China Focus at The Carter Center will be hosting a book talk with Terry Lautz and one of the book’s authors, Melinda Liu. You can find more information about the event here.

Terry Lautz is a Fellow at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). After retiring from the Luce Foundation as vice president and secretary, he taught and directed the East Asia Program at Syracuse University. Dr. Lautz has served as board chair of the Harvard-Yenching Institute, Lingnan Foundation, and Yale-China Association. He holds degrees from Harvard College and Stanford University.

Deborah Davis joined the Yale Department of Sociology as a lecturer in 1978 and held fellowships from the National Academy of Sciences, National Institute of Aging, Luce Foundation, Templeton Foundation, Ford Foundation, and the ACLS. Since 2016, she has been a Distinguished Visiting Professor at Fudan University in Shanghai and on faculty of the Schwarzman College at Tsinghua University. She also serves on the editorial boards of The China Quarterly and The China Review and is a Trustee of the Yale China Association.

Miranda Wilson: To begin, would you mind giving a brief overview of Chinese Encounters with America? What are the themes? How is it organized?

Terry Lautz: The book has twelve stories about individual Chinese from different backgrounds who came to the United States and returned to the PRC. They’re involved in diplomacy, business, education, science, sports, culture, and civil society. They were not tourists. They were digging into American culture and society to get a deeper understanding from the perspectives of their own professions.

The key question is: What difference did these encounters make when they went back to China—in terms of their own lives, their institutions, their professions, and in US-China relations? How did they adapt new ways of thinking during a period when China was rapidly changing? We focus primarily on the period after normalization of US-China diplomatic relations in 1979 up to the present. We hope these stories show the benefits of interacting with China. In addition, Americans need to understand Chinese points of view beyond official policy statements.

Deborah Davis: In the title, we lead with the word “encounters” to foreground the importance of engagement, exchange, and entanglement rather than exclusion, estrangement, or enmity. An emphasis on encounters also puts the lived experience of these individuals front and center.

MW: Chinese Encounters with America is sort of a part two to Terry’s Americans in China. Were there any surprising differences or similarities you noticed when comparing “Americans in China” versus “Chinese in America”?

TL: The differences are stark. Both sides have very different perceptions, motives, and assumptions. In the past, Americans have been idealistic about China because of a longstanding ambition to change China and make it democratic or capitalist or Christian. The Chinese, by contrast, have been a lot more pragmatic. That’s because of their own history; they had to be realistic about how China could recover from war, poverty, foreign incursions, and natural disasters. We say in the book that China made use of the United States as a gravitational slingshot in its quest for modernization, just as a spacecraft uses the gravity of another planet to increase its speed. That other planet is the United States, and the primary way in which China used it was through education. So, there’s been a big mismatch of goals and objectives between the two countries.

DD: We also emphasize individual trajectories. At the individual level, there’s a personal quest, distinct from the goals of national leaders.

MW: In the introduction, you write, “the cross-pollination of minds described in these chapters illustrates the value of shared interests and common goals amid the perpetual swings and shifts in Sino-American relations.” What are some of these shared interests and common goals? Feel free to use examples from the chapters of the book.

DD: I’m a sociologist, so it’s hard for me to generalize about values at a national level. However, at the personal level, in both societies, there is a strong desire to create security for family. That’s one of the things that draws us together, this shared focus on family security and success. A second shared interest is lifelong friendship. In both societies, there is a sense that friendship is important, and, on the basis of friendship, you can do a great deal for your country as well as for yourself. The third is teamwork. In both societies, there’s a high value placed on teamwork. It’s not that other societies don’t value teamwork, but for most Chinese and Americans, it is a shared value.

At the same time, I observe a shared emphasis on self-reliance and personal autonomy. Often, people talk about collectivist China in contrast to individualistic America. For me, that distinction does not hold up, and again and again we find Chinese parents, like their American peers, stressing the need for their children to have self-esteem and be self-autonomous persons.

TL: These “shared interests and common goals” are underpinned by bilingual and bicultural skills. Ji Chaozhu and Hung Huang, the subjects of two chapters (by Charles Hayford and Melinda Liu, respectively), were sent to the United States at a very young age to learn as much as possible about America. Both of them developed a remarkable ability to bridge gaps and interpret one side to the other. Ji became a diplomat and interpreter to Zhou Enlai, Mao, Nixon, and Kissinger. Hung became an entrepreneur and an extremely popular social influencer.

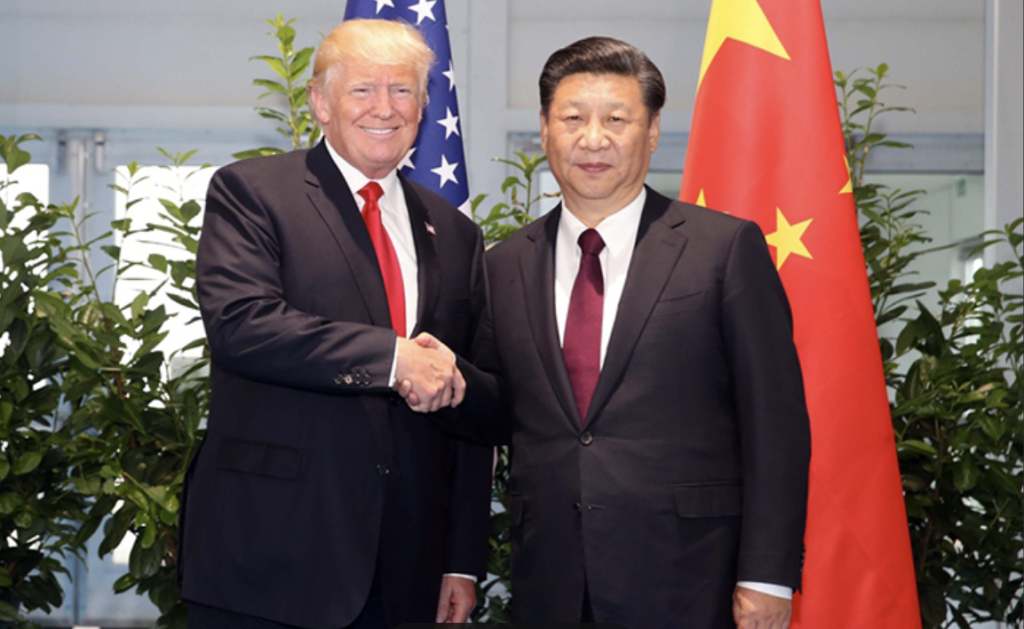

MW: The introduction talks about the importance of education exchange, especially for Chinese students studying in America, in an effort to modernize the country. The Trump administration recently announced it would revoke Chinese international students’ visas, but then shortly after, said in a briefing that, “Chinese students are coming no problem. It’s our honor to have them.” What are the consequences of these inconsistent policies?

TL: The uncertainty about student visas has done damage in both countries. If this is a negotiating tactic, then it’s unfortunate because it’s already caused considerable harm. There’s great fear and anxiety on the part of Chinese students.

America’s success in building soft power and having influence is being eroded by “America First” policies that lead in the direction of isolation. One of the ironies here is that the more the United States restricts China, the more it imposes sanctions on semiconductors or other forms of technology, the more incentives there are for China to be self-reliant. We’re already seeing evidence of this in the rapid progress that China is making on AI and other fields.

DD: It is also worth mentioning that there are some on both sides of the Pacific who endorse reducing the number of Chinese students in the US. Americans who have embraced the current President’s policies on tariffs and immigration would also prefer fewer foreign students on American campuses. Similarly, there are ultra-nationalists in China for whom the issues of brain drain and cultural contamination are not trivial. At the same time, however, there are more than two hundred thousand Chinese students still enrolled in U.S. degree programs who are uncertain, confused, and angry; many of them now feel marooned.

MW: What are some of the challenges Chinese people face when coming to live in America?

DD: Language is the first issue. Xie Xide, in Chapter 2, hailed as the mother of the Chinese semiconductor, who had attended English language schools in China, wrote about how her year at Smith College dramatically improved her English.

A second challenge is social isolation and particularly the absence of family or friends nearby. Anyone who moves to a foreign country experiences that loss, and while those profiled in this book eventually made friends or found mentors, almost all felt the absence of family support.

Third, for many who come from China, and certainly for almost all our characters, there is an obligation to fulfill not only their professional goals but also the dreams of the nation.

TL: Yes, having to deal not only with your own expectations, but the expectations of your family, your friends, and your leaders is huge.

Another challenge in coming to America is the reality of racism, anti-Chinese, and anti-Asian hate. We saw this particularly during COVID, but there’s a long history of it in the United States. At the same time, there’s a very positive legacy of welcoming Chinese students even when there was exclusion of workers.

I would add that both sides have been challenged by stereotypes from propaganda and political rhetoric. We saw this particularly during the Cold War; people in the early chapters of the book grew up hearing extremely negative stories about US imperialism and American soldiers during the Korean War. After they met Americans in China or came to the United States, they completely changed their thinking.

This shift in attitudes is why we decided to include two chapters on America watchers. Zi Zhongyun and Wang Jisi (by Steve Levine and Mike Lampton, respectively) both made a radical transition from a one-sided Marxist interpretation of the United States as a bourgeois, capitalist, aggressive country to a much more nuanced understanding of American domestic and foreign policies. It’s revealing for Americans to understand how outsiders see us.

MW: Chinese Encounters tells the stories of people and their professions over three eras. Would you mind expanding on the different themes in each era and maybe sharing an example?

TL: The first generation we outline in the book describes people who were motivated primarily by patriotism, and a drive to make China stronger—to modernize China. What were the keys to unlock the success of the West? The second generation focused on rebuilding China in the wake of the devastation of the Cultural Revolution. The third generation was driven by prosperity within China. Nationalism and patriotism are important, but they are more interested in the skills they can apply to new opportunities in a China that is increasingly wealthy. There’s a dramatic shift over time in the reasons for coming to the United States.

DD: In the first part of the book, we feature people who were born before 1949, who grew up when the United States and China were allies in the Second World War. They are members of an educated elite. They are, however, representative of the largest number of those who came to the United States in that decade. This was not an era in which laborers could come to the United States.

For example, the person Richard Madsen and I wrote about is the physicist Xie Xide, who was born in 1921 in a cosmopolitan part of South China that had sent people overseas for generations. Both her father and her grandfather got PhDs in the United States. But she came of age during the Second World War when Japanese incursions drove the family from their home in Beijing, then again from refuge in Changsha, and finally into the mountains of Fujian. The end of the war provided a brief opening, during which time, she finished university, and then received a visa and a scholarship to study in the US. By the time she completed a PhD at MIT in 1951, China and the US were no longer allies, and US policy blocked the return of STEM students because of national security issues. However, with great ingenuity, and not a trivial measure of luck, she created a workaround—the US government would allow her to leave and get married in the UK if she agreed to come back. She left in May 1952, married in the UK but promptly returned to China, where until the Cultural Revolution struggles demoted her to cleaning toilets, her MIT doctorate set her on a path of professional acclaim.

Then, after 1974, geopolitics shifted again, and she was rehabilitated. She returned to Fudan University, by1983 was the president of the university, and in 1984 welcomed President Ronald Reagan to China.

TL: Even before Xie Xide arrived in the United States, like many others in her generation, she had deep exposure to American education, ideas, and values through the network of missionary schools. She not only began with primary school on the campus of Yenching University, but subsequently attended Bridgeman Academy in Beijing, St. Hilda’s School in Wuhan, and Fuxing in Changsha. These schools were small but influential.

MW: Chapter Seven (by Susan Brownell) covers Lang Ping, a famous Chinese women’s volleyball player. Sports have often been important to US-China relations; another example is ping pong diplomacy. How do sports unite us and how can athletes play a role in people-to-people relations?

DD: Lang Ping is an incredible volleyball player whom I first saw in 1981 on TV in Wuhan. So, she has a big place in my heart.

If we talk about the role of sports in U.S.-China relations or the role of sports for China to reach the global stage, the Olympics is the crucible in which that happened. Lang Ping is an Olympic athlete who has an extraordinary story of not only achieving individual wins but also coaching both Chinese and American teams to gold and silver medals—which led Chinese citizens to ask if she was a patriot or a traitor. She is unique, but her story speaks more generally to your question about how sports unite us and how athletes play a role in people-to-people relations. But the role of sports does vary over time.

For example, if we focus on the contemporary period, rather than 1972 when the first ping-pong team visited the US—their arrival is featured on the cover of our book—or 1984 when China won its first Olympic gold in a team sport, we can’t avoid acknowledging the commercialization of sport which has made some individual Chinese players multimillionaires. Over the decades, the degree to which the Chinese government can deploy athletes for national goals has declined, and world-class Chinese athletes like their American peers often operate like global free agents.

TL: Sports certainly does provide common ground and reaches across national boundaries. The same thing is true for music (in a chapter by Sheila Melvin and Jindong Cai) and dance (by Emily Wilcox). These are less politically charged. It’s not an accident that the modern U.S.-China relationship started with ping pong diplomacy, a sport where the Chinese were so much better than the Americans. China’s mantra in those days was “friendship first, competition second.” But it quickly became clear that winning competitions and medals was an important source of national pride. For China, success in sports is evidence of being a modern nation, of being accepted by the rest of the world. It is a big part of their globalization narrative.

DD: For both the American and Chinese governments, geopolitics can impact Olympic competition and the autonomy of some athletes, but Lang Ping’s professional trajectory—playing and coaching in Europe, the US, and China—demonstrates how sports can offer people-to-people connections even in years when governments promote estrangement. In sports, the best athletes (and their fans) seek competitors who are also peers.

MW: The conclusion is titled “The Paradox of America.” What did you mean by this phrase? What do you think this book says about the myth or reality of the “American Dream”?

TL: America is a paradox of extremes. We see extremes of wealth and poverty, equality and racial discrimination, safety and gun violence—the list goes on. American individualism can be very attractive and liberating, but it can also be alienating. The “America First” isolationism that we see now has certainly tarnished the American dream, I’m sure, for many people.

Chinese coming to the United States and going back to China to adapt what they have learned is not a simple process of “cut and paste,” as Elizabeth Knup writes. It’s not just copying American models of business education or sports or environmental policies. It’s a very complex process. How did they take new ideas that might advance China and reconfigure them for Chinese circumstances? I believe this learning process, this mutual understanding, will not disappear; it will persist.

Some Americans say engagement with China was a terrible mistake and is over and done with. I disagree because there is so much more to the relationship than national security. I’m optimistic that personal diplomacy and human relations will outlive our current political issues, just as they have in the past. After the Cold War, Chinese who had previous experience with the United States were essential in rebuilding the relationship. Newer generations of Chinese who understand America will play major roles in sustaining the relationship in the future.

I will end by saying: engagement is not dead.