Japan’s Prime Minister Takaichi Finally Says Something Close to What Beijing Wants to Hear

Chinese Scholars Debate the Role China Could Play in the Russia–Ukraine Peace Process

- Opinion

China-Focus-Editor

China-Focus-Editor- 08/22/2025

- 0

The high-stakes Ukraine summits convened by President Trump have captured the world’s focus. As the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and European nations navigate a complex diplomatic landscape, China’s silence on the matter is particularly noteworthy. This, of course, is not surprising, as China is not a direct participant in the conflict.

However, Wang Huiyao, the founder of the Center for China and Globalization (CCG) in Beijing, and Hu Xijin, the former editor-in-chief of Global Times—both prominent voices in China’s media ecosystem—have expressed their views, arguing that China can still play a role in the Russia–Ukraine peace process.

The official Chinese stance has consistently been to support both sides in bringing the war to an end as soon as possible. On Monday Beijing time, after the Trump–Putin meeting in Alaska and before Trump’s White House talks with Ukraine and Europe, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning reiterated China’s position of supporting peace in Ukraine. She said that China supports all efforts conducive to the peaceful resolution of the crisis, welcomes contacts between Russia and the United States, and encourages them to improve relations and promote a political solution to the Ukraine crisis.

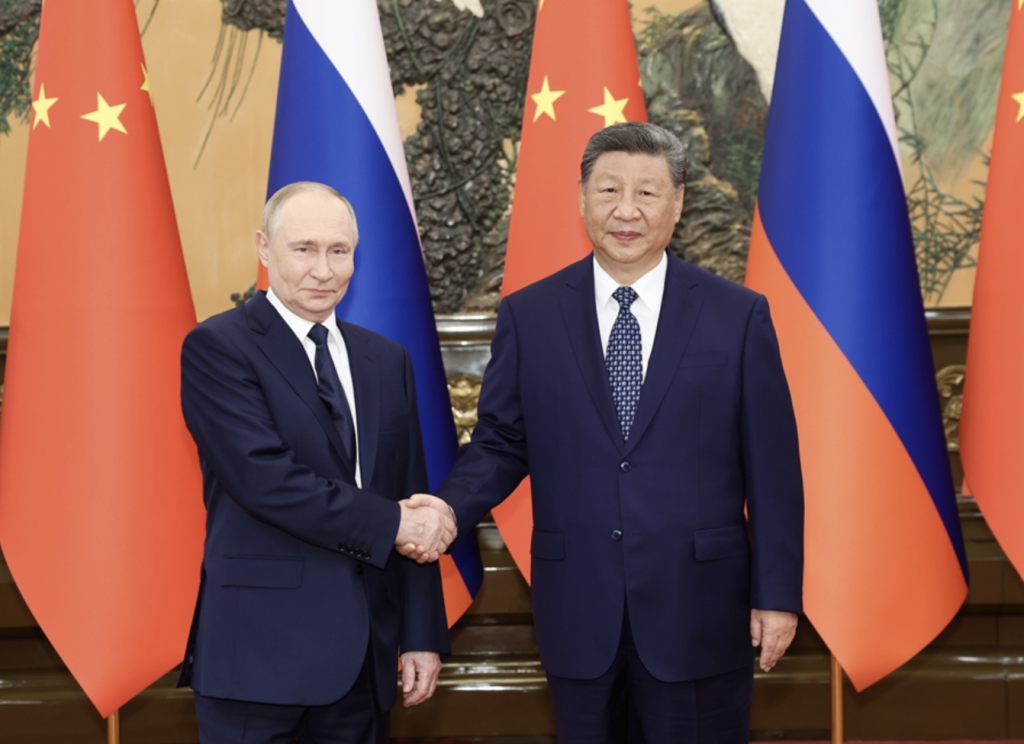

Over the course of more than three years of conflict, the West has accused Beijing of maintaining business ties with Russia, particularly its continued purchases of Russian oil, which they argue sustain Moscow’s warfighting capacity. From Beijing’s perspective, however, China not only maintains trade relations with Russia but is also Ukraine’s largest trading partner. Therefore, claims of partiality are unfounded.

What role, if any, does China hope to play in the upcoming peace process?

Below we present excerpts from three analyses by Chinese scholars and media commentators on this issue: Hu Xijin, Wang Huiyao, and Professor Da Wei of Tsinghua University. Each elaborates on the potential influence or role China could play in the Russia–Ukraine peace process. Among them, Hu emphasizes the positive impact of China’s support for the peace process, Da Wei argues that China cannot play a central role but only a participating one, while Wang envisions a substantive role for China in Ukraine’s future security guarantees.

Hu Xijin wrote in his article:

“China is an invisible yet powerful presence in the Ukraine peace process. Whether China supports U.S. mediation of the Russia–Ukraine conflict, and whether it supports and cooperates with the peace process, will make a decisive difference.”

The following is his analysis:

First, China has openly stated that it supports all efforts conducive to the peaceful resolution of the crisis, welcomes contacts between Russia and the United States, and encourages them to improve relations and advance the political settlement of the Ukraine crisis. This genuine stance is significant. China is not undermining Trump’s efforts to end the Russia–Ukraine conflict because ending the war benefits China. A ceasefire would further open up China–Russia trade. After hostilities cease, China could export dual-use equipment to Russia without the West having grounds for objection. In addition, a major irritant in China–Europe relations would be removed. Europe has long accused China of exporting “dual-use products” to Russia, alleging that Beijing is helping Moscow sustain the war and questioning China’s neutral position.

Trump is pushing Putin to end the war by meeting Russia’s basic demands on territory and postwar arrangements, while simultaneously applying pressure through harsher sanctions, especially by imposing “secondary tariffs” on Russian oil. If such tariffs are enforced, China would be hit first, aside from India, which has already faced tariff hikes under this justification. On oil, the U.S., Russia, and China form a triangular cycle of pressure, making China’s cooperation crucial to achieving peace. If China chooses to confront the U.S. and signals support to Russia, Putin could grow tougher and raise more demands from Trump.

China and the U.S. have already fought one major round of tariff battles. A tariff truce benefits both sides, but fundamentally, China is not afraid of another round. Currently, India faces increased tariffs for buying Russian oil. Yet on August 15, Trump stated that he would not, for now, impose tariffs on China for purchasing Russian oil, though he added he “may have to consider it in two or three weeks.” Trump’s nuanced remarks reflect the “pressure-transmission triangle” between China, the U.S., and Russia—a unique pattern.

China has not indicated how it would respond to “secondary tariffs,” and official discourse rarely connects the issue directly to China. This stance has surely been carefully interpreted by all parties. Combined with China’s declared support for peace, this provides encouragement for the U.S. and Russia to work out a feasible peace plan. For if the peace process fails, how China might respond remains uncertain.

On August 13, Wang Huiyao, founder of CCG, published an article in Foreign Policy titled “China Can Help Trump and Putin End the War in Ukraine.” He argued that a seven-party meeting in Beijing (involving the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, Ukraine, and the EU) could pave the way for the deployment of UN peacekeeping forces, thereby promoting regional peace and stability.

He wrote:

“ True peace will require more than just the involvement of the United States and Russia. It also requires Ukraine, Europe, the United Nations, and China.”

Wang continued:

China is uniquely positioned to help break the gridlock. Beijing can convene a follow-on summit bringing together Ukraine, Russia, the United States, and Europe, leading to a face-to-face meeting among the leaders of all these players. The goal would be to create a formal seven-party talks framework consisting of the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council, plus Ukraine and representatives from the European Union.

China has both the diplomatic standing and economic leverage to pull this off. It remains both Russia’s and Ukraine’s largest trading partner, at $240.1 billion and $12.8 billion, respectively, in 2023. Both Russia and Ukraine are members of the Belt and Road Initiative, and China is particularly invested in the stability of Ukraine’s grain exports. As a result, Beijing can offer Russia the off-ramp it needs and provide reconstruction and recovery assistance to Ukraine.

A seven-party talks framework avoids forcing one side to capitulate to the other’s narrative. Instead, it works to reframe the problem by seeking out shared interests—such as nuclear safety, regional stability, and an end to the human misery created by active fighting—that can be de-linked from more contentious zero-sum debates. ……..

An effective peacekeeping force could be composed of a mixture of nonaligned states and European ones. This would offer a politically viable middle ground, allaying fears on both sides of the conflict. Their physical presence would inhibit future conflict and ensure the beginning of a reconstruction process. Such a force could be composed of five European countries—such as Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Poland, and Italy—and five BRICS nations such as China, Brazil, India, South Africa, and Egypt. This arrangement would underscore neutrality and also distribute responsibility, thereby ensuring broad-based legitimacy and a durable security guarantee.

The BRICS countries’ relative distance from European security affairs can be turned into an advantage. Because they are less historically entangled, they are more capable of offering creative guarantees and confidence-building measures that all parties can accept. These should include not only peacekeeping support but also long-term development assistance.

Plans for postwar recovery will be vital. The task of rebuilding Ukraine requires sustained international effort—not only financial, but also logistical and technical. BRICS countries, especially China, have the engineering expertise and financing capacity to aid in reconstruction. China’s participation would not only help accelerate Ukraine’s recovery but also demonstrate Beijing’s wider commitment to peace, stability, and inclusive development. Within this framework, smaller working groups could tackle specific challenges: humanitarian access, territorial disputes, energy infrastructure, and long-term security guarantees—each reinforced by a more diverse coalition of contributors.

Professor Da Wei, Director of the Center for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University, published an article in Foreign Affairs on July 29 analyzing China’s role in the Ukraine issue. He also addressed the potential role China might play in future peace talks, concluding that China cannot be a central player but could participate. He wrote:

Theoretically, China is well positioned to bring the countries to the negotiating table. China has taken an increasingly active role in mediating international conflicts in recent years, including negotiating a deal that restored ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and brokering peace between Russia and Ukraine would remove a major obstacle to improving China’s ties with Europe. Such a breakthrough could also steer the international order toward greater multipolarity and push back against the hardening binary divide between China and Russia on one side and the United States and Western countries on the other. If China were to succeed in bringing the war to an end, it would bolster its international image as a responsible world power.

The reality, however, is that China is unlikely to play a central role in resolving the conflict. Any role it would play would be secondary, at most, and limited to participation. If a multilateral peace process were to take shape, China would gladly take its place at the table if invited. But Russia and Ukraine are the direct parties to this war, and the United States and Europe are indirect participants through military aid. If the two primary belligerents—Russia and Ukraine—are unwilling to stop fighting, and if both remain wary of postwar cease-fire security guarantees, China will not succeed as a third-party mediator.

China’s geopolitical ties also constrain its ability to effectively mediate the conflict. China’s friendly relations with Russia limit its room to maneuver because Beijing is reluctant to pressure Moscow to make major concessions. China’s strategic culture shapes its diplomacy: when a country is broadly aligned with China, Beijing is hesitant to criticize that country’s specific policies—even if it privately disagrees. Western nations have repeatedly urged China to use its might to pressure other countries—including Iran, North Korea, and Sudan, along with Russia—but China usually rebuffs these appeals.

Meanwhile, China’s strained ties with the United States and Europe further limit its potential effectiveness as a mediator. Ukraine and Western countries may not want to see China lead peace talks even if it were willing to do so, likely because they believe China would push for a settlement favorable to Russia. If other parties brought an end to the war, Chinese leaders would then hope to contribute to peacekeeping and postwar reconstruction efforts. But China is unlikely to take the lead in bringing the parties to the table in the first place.