Interview with Zhou Wenxing: Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations in the Next Few Years—Is War Inevitable?

Democracy in Blue Jeans w/ Larry Diamond

- Interviews

Diego Ge

Diego Ge- 08/04/2025

- 0

Larry Diamond is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and the Mosbacher Senior Fellow in Global Democracy at Stanford’s Freeman Spogli Institute. He chairs the Hoover Project on Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific, leads programs on Arab reform and digital policy, and coedited the influential report China’s Influence and American Interests. A founding coeditor of the Journal of Democracy and senior consultant to the National Endowment for Democracy, Diamond focuses on global democratic trends and strategies to defend liberal democracy. He is the author of several books, including Ill Winds, and has edited or coedited over fifty volumes on democratization. He teaches political science and sociology at Stanford, and has advised institutions like USAID, the UN, and the World Bank. In 2004, he served as a senior governance adviser in Iraq. Diamond holds a B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. from Stanford and previously taught at Vanderbilt University.

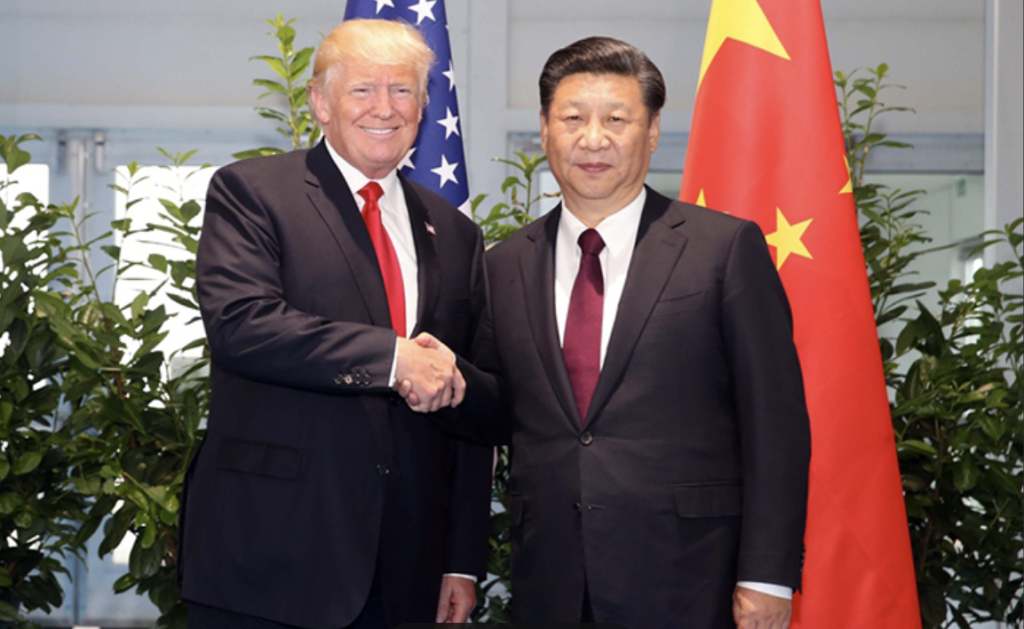

In this interview, Diamond discusses his thoughts on the Trump Administration’s China and Taiwan policies, the state of Taiwanese democracy, and the future of global democracy in a post-Trump era. He argues that America should abide by Teddy Roosevelt’s principle of “speak softly and carry a big stick” as it processes China’s rise as a superpower. He suggests that while the Trump administration has done significant damage to the image of American liberal democracy on the global stage, it could also be an opportunity for other liberal democracies to take on a more substantial role in democracy promotion, and that in the long run, people should not “count America out.”

(source: Untitled [Allegorical Map of Freedom and Oppression]. Peter Sís. 2007. Source.)

Diego Ge: Thank you for speaking with me today. Since its inauguration, the Trump administration has imposed restrictions on major universities like Harvard and Columbia, ranging from international student admissions to on-campus organizations. Has this impacted Stanford or the Hoover Institution? What do you think more broadly about these actions?

Larry Diamond: The Hoover Institution is not a teaching institution, so we’re not directly impacted—although we do hire student researchers and fellows who also teach. I’m not aware of any instance where a Stanford student has failed to get a visa to come here. There may have been some isolated incidents, but I’m not aware of them. I’m also not aware of any visiting scholar at Hoover or Stanford failing to get a visa. We have an international fellows program and a summer fellows program at our Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law, and almost all—though not quite all—of the people we’ve admitted have been able to get visas. So, so far, so good on that front for Stanford.

DG: The administration has tried to block Chinese students from coming into the country, justifying it with concerns around national security. Do you think these concerns are justified? Should America be using visa bans to protect its national security?

LD: I think a selective approach would be justified and appropriate—not a sledgehammer or indiscriminate one. I think it’s a disastrous policy to deny visas to Chinese students and scholars purely on the basis of their nationality. It’s a terrible policy for multiple reasons.

First, many of the students and scholars who would be coming here are people who share our values and would like to see China become a more open and pluralistic society. We’re squandering the opportunity to engage with, educate, empower, and build ties with people who might actually be a bridge to a better U.S.–China relationship.

Second, from decades of experience, we know many of the Chinese students who come here bring skills, intellectual ability, and professional ambitions—all of which can help make America great again. They can help build a stronger, more vibrant, technologically innovative, and economically prosperous country. Some might stay and become Americans, contributing to what has always been the miracle of American society—our history as an immigrant country. Why would we want to foreclose that continuing enrichment?

Third, many graduate programs in the U.S., particularly in science, engineering, and computer science, really depend on international students. They’re predominantly populated by international students, and disproportionately by Chinese students. These programs would be seriously hampered if we started radically and indiscriminately reducing international student numbers, especially from China. At one point, we had 350,000 Chinese students in the U.S., most paying tuition. That number is now down, I think, by at least 30%. That’s a major economic loss. When students come here and pay tuition, room, and board, it counts as an export of services—it actually helps our trade deficit with China, something that Trump seems very worried about. Why would we sacrifice that?

Now, the other side of the story is that some students, particularly at the graduate level and in sensitive technological areas, may come here with other motives or under instructions from Chinese state institutions. There’s a real concern about compromising U.S. technological secrets, especially through China’s civil–military fusion program or through universities tied to China’s “Seven Sisters of National Defense.” So, I’m not saying we shouldn’t vet applicants. Especially in technological fields like computer science, physics, chemistry, bioengineering—we absolutely need to vet. But if there aren’t specific reasons to reject a student, we should bring them here. That’s my policy.

DG: That brings me to a broader question—we’ve seen a lot of contradictory discourses and narratives from the White House regarding China. What would you say characterizes the administration’s China policy? Is there a coherent framework guiding it?

LD: I don’t know how to characterize it. It seems disjointed, disarticulated, unclear, and ambiguous. On the one hand, it’s obviously confrontational, especially on tariffs. But even there, a more coherent approach could have been taken. We’re doing some good things on Taiwan—helping Taiwan better prepare to defend itself, deterring unprovoked Chinese military pressure or action—but I don’t see a coherent policy yet. I think the right approach is the Teddy Roosevelt doctrine: speak softly and carry a big stick. We should be clear with the PRC and its leadership that we recognize China as a great power. That’s just a fact. And that reality has two implications. First, the Chinese people and their leadership expect respect. Respect isn’t deference, but it’s also not a gratuitous insult or sweeping restrictions. And our visa policy, for example, broadly insults the Chinese people. That’s a mistake.

Second, we need to make it clear we won’t tolerate United Front activities on U.S. soil, or transnational repression—things the PRC has been doing here, in Canada, and elsewhere. We won’t stay passive in the face of global propaganda campaigns. I think if TikTok isn’t sold and radically transformed, it should be banned. TikTok is an incremental propaganda tool—it’s a frog-in-the-boiling-water situation. We won’t allow bullying in the South China Sea or across the Strait. That means stronger support for the Philippines and regional stakeholders and accelerating the delivery of weapons to Taiwan—not to provoke a conflict, but to deter one. I don’t believe we should change our policy of strategic ambiguity. Declaring a formal commitment to defend Taiwan would be destabilizing. But through our actions—deployments, enhancements—we can quietly make clear to Beijing that if they are reckless enough to launch an invasion, blockade, or forced resolution of the cross-Strait issue, they will be facing not just Taiwan but the U.S. and its allies.

DG: Do you think China is now more or less confident on Taiwan since Trump returned to power earlier this year, compared to when Biden was in office?

LD: Hard to say. You could draw multiple, speculative inferences. I prefer not to speculate too much, but I’ll note both sides. On the one hand, Beijing might say: “Trump is an isolationist, transactional, unpredictable—maybe he won’t fight to defend Taiwan.” On the other hand: “Trump is unpredictable and has increased military spending and deployments. He bombed Iran. Maybe it’s not worth the risk.” It’s an unfolding story, and we just don’t know. What I can say is that our actions, including deployments, policies, and weapons flows, must clearly signal what our response would be. Also, look at what China’s doing. They are continuing, and arguably accelerating, the most rapid military buildup since the Cold War, maybe even since the 1950s. It’s overwhelmingly offensive in character. A lot of it is clearly aimed at preparing for a military resolution of the Taiwan issue.

DG: Taiwan’s domestic politics have moved more strongly toward posturing for independence. They recently designated the PRC as a “hostile foreign force” and proposed new security strategies, including screening residents with mainland Chinese IDs. There was also a deportation of a mainland immigrant for advocating ‘unification by force’. Are these justified, or do they cross democratic lines? Is it fair to compare mainland immigration to Taiwan versus immigration to the U.S.?

LD: It’s enormously complicated, and you have to take these issues one by one. First, I think it’s grossly unfair to apply the same standard to Taiwan as to the United States. Taiwan is an incredibly vulnerable democracy, with 23 million people living under the constant shadow of a neighboring authoritarian power. If someone in the U.S. advocates for Taiwan being absorbed by the PRC, it’s a drop in the bucket, not particularly relevant. But in Taiwan, it’s a potential security threat.

There is no doubt that there are PRC agents in Taiwan. And of course, Beijing is trying to absorb Taiwan—not through war if they can avoid it, but through internal subversion. After Hong Kong, Tibet, and Xinjiang, it’s clear what the pattern is. They’d prefer to swallow Taiwan without force and without triggering sanctions. They’re running a parallel strategy: gray-zone activity like military incursions, cyberattacks, media pollution, and information warfare. Some of what they do in Taiwan, they’re doing here too. Taiwan’s vulnerability means they have to be more vigilant than we are.

Frankly, a lot of what Taiwan is doing, it’s hard to fault. And we should be cautious about criticizing. They haven’t done things they could’ve done—like banning TikTok, which I think they should. There’s evidence that TikTok in Taiwan sways youth toward PRC narratives. They haven’t banned PRC-influenced publications either. Taiwan remains a liberal democracy—arguably the most liberal in East Asia. Probably even more so than Japan or Korea. That’s remarkable given their existential security threats.

The area where I’m most critical is rhetoric. President Lai, whom I like and respect as a sincere, idealistic democratic leader, has been pushing the envelope symbolically—especially in the recent ten-speeches series. When you’re sitting across from a massive military buildup, is it wise to rattle the tiger’s cage with provocative rhetoric? I would urge more rhetorical restraint.

DG: The DPP’s stance has been that ROC Taiwan is already an independent country, so there’s no need for formal declaration. But President Lai seems to have pushed that a bit further rhetorically.

LD: That basic stance—ROC Taiwan is already independent—goes back to Chen Shui-bian. But Lai has rotated the language slightly, added nuances that aren’t helpful. I don’t remember exact quotes, but they came up early in his speeches. Again: speak softly and carry a big stick.

DG: Yeah, I think what we’ve seen from the U.S. administration recently is more like: speak harshly and then don’t wield the stick when pressed. Especially with the trade war—it feels inconsistent.

LD: That’s the worst possible combination in international affairs, especially when dealing with a rising superpower.

DG: How would you compare Trump and Xi’s authoritarianism?

LD: I’d say two things. First, Xi does seem to have a coherent strategy—he’s more patient, more relentless, more focused. That makes him more threatening than Trump. Second, we’re at a moment in China’s internal politics where it’s hard to know what’s going on. It’s a bit of a black box. There’s a line of analysis floating around that Xi has been less visible lately, skipping meetings and international summits, because he’s in physical decline—maybe some strokes, not massive, but cumulative. That his capabilities are diminished. And that figures in the system who are unhappy with his concentration of power are starting to reassert themselves.

Some say we might start seeing signs of a leadership transition at the Fourth Party Plenum this fall, that this could be Xi’s last term as president and General Secretary. And that a new leader might emerge over the next year: one more focused on internal economic challenges than on risky foreign adventures. By this interpretation, China might pose less of a threat to Taiwan in the next few years, not because they’ve given up on reunification, but because they want to shift focus inward.

Now, there’s a big debate about whether that’s true or complete fantasy. China’s not transparent. I don’t have a strong opinion because I’m not a China scholar. I’m one step further removed than even the less-informed China scholars. But I do think it’s possible that something is shifting inside the system. And by the end of the year, we might know more.

DG: Another part of the Trump–Xi comparison involves targeting of academic institutions, political speech, and activism. Some have said Trump is pulling from the same authoritarian playbook. Would you say that’s accurate, or are there major differences?

LD: It’s hard to say, partly because I don’t know that the current Trump administration really has a coherent strategy. There’s so much internal dissonance—between the White House, the State Department, the Secretary of Defense, Peter Navarro in trade, and so on. Now, there are reports of the Secretary of State and Ambassador Grinnell behaving in totally contradictory ways on Venezuela. Who knows what the strategy even is?

DG: That’s fair. But in terms of methods—targeting dissent, academic freedoms, political expression—would you say there are authoritarian parallels?

LD: Yes, I’ve written extensively on this. We’re experiencing democratic backsliding in the U.S., and Trump clearly has authoritarian instincts—he’d like to be king for more than a day. And there are people around him who also have authoritarian intent. Congress, and sadly, now the Supreme Court, have done little to constrain him.

We’ve seen many elements of the authoritarian playbook that played out in places like Hungary, Turkey, Serbia, Venezuela, and India. We saw it during Trump’s first term, and we’re seeing it revived now with even more energy. It’s nothing like China—China is a full-on Leninist, neo-totalitarian regime. But within the context of global democratic regression, yes, the U.S. is showing signs of the same pattern. We’ve become a less liberal democracy. Media, law firms, and institutions are making concessions under intimidation. The long-term trajectory is uncertain, but it’s meeting resistance.

DG: After everything the world has seen, including the decline in credibility of American liberal democracy, do you think America can return to the early 2000s role of global democracy promoter?

LD: That’s a really good question. Right now, we have very little credibility because of Trump’s unilateralism and authoritarian mindset—and because of the wholesale dismantling of our international engagement tools. I’m talking about USAID, Voice of America, the State Department’s Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor Bureau, the attempted termination of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Most scholars and policy folks now write about that era as over. The world no longer sees the U.S. as credible or capable of leading on this. That’s true, for now.

But let me say two things. First, in the short term, democracy and human rights support will have to become more multilateral. That may be a good thing. Europe, Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea—they need to step up. Countries like Norway and Sweden have always punched above their weight. We need more of that. Institutions like the European Endowment for Democracy have to take on a greater role. Second, I’d caution people against counting the U.S. out for the long term. I think Trump’s authoritarian project is going to collapse during this term. He’s already overreaching. The border wall is a monstrosity that will be rejected. His foreign policy will exact a high cost. There will be political consequences.

So, be patient. Don’t resign yourself to despair and assume the American people have turned isolationist forever. I don’t buy that. I think this can be revived—but the U.S. won’t be the sole global leader of democracy promotion for the foreseeable future.

And maybe that’s a good thing. Maybe a more multilateral, shared framework will be more sustainable and legitimate in the long run. So I’d say: don’t draw premature conclusions.

Diego Ge is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and studies Political Science and International Comparative Studies at Duke University.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.