Remembering Joseph Fewsmith: The Passing of a Generation of China Hands

Trump’s Bad for Business Big & Small w/ Arthur Dong

- Interviews

Edison Chen

Edison Chen- 06/24/2025

- 0

Arthur Dong is a teaching professor of strategy and economics at the Georgetown University McDonough School of Business. Professor Dong is a long-time expert on U.S.-China trade relations and China-focused international economics and geopolitics and a frequent contributor to major media networks including the Wall Street Journal, Fortune, and The Hill.

In this interview, we cover the history of U.S-China trade relations and the evolving tariff war between the United States and China, including its impact on U.S. firms investing in China and American small businesses. We also discuss soft diplomacy in higher education, food, and entertainment as a crucial complement to formal U.S.-China diplomacy. Dong emphasizes that U.S.-China trade tensions will increase the burdens on American small businesses, but will also hurt China’s currently challenged economy. Dong concludes by reflecting on his journey of exposing his U.S. students to the real China experience through trips to China, and praises cultural outreach as an effective way of diplomacy.

Edison Chen: Professor Dong, you have been studying international economics since the 1970s. Can you briefly explain how U.S.-China trade policies changed since they’re establishment during the Reform Era?

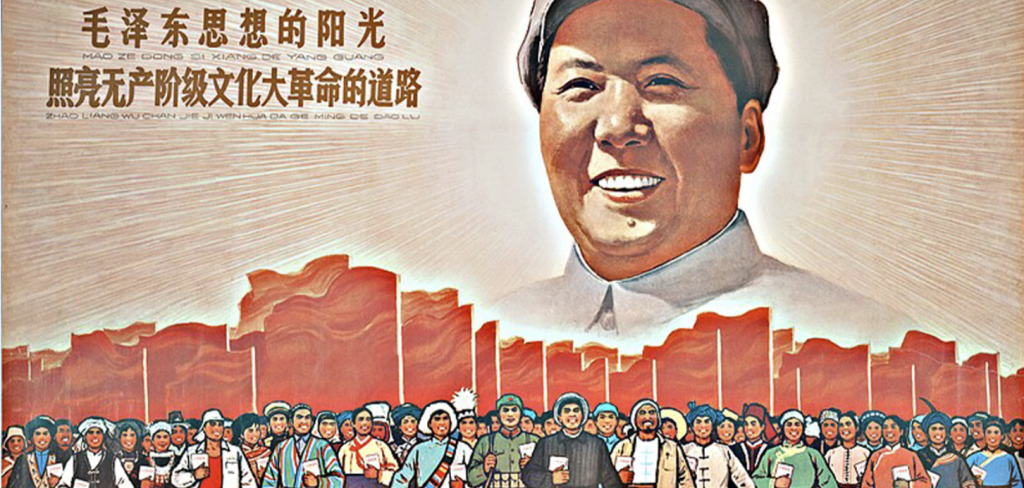

Arthur Dong: This is a big question regarding how U.S. policy has changed as it relates to China. Let’s take this back several decades: China initiated its reform after the passing of Chairman Mao Zedong, in September of 1976. From the end of World War II through the Mao era, China was a self-isolated economy. There was a power vacuum as a result of the passing of Mao, and the party leadership of the Chinese Communist Party was confronted with two forks in the road: Do they remain on the Maoist and conservative path, or do they take this as an opportunity to move forward and introduce a new era of economic change within Chinese economy? There was a power struggle between these two factions of the Communist Party, and the reformist faction came into sharper focus, anointing President Deng Xiaoping as the new leader of the Chinese Communist Party. This happened around 1978. It was also coincidentally during the period of President Jimmy Carter. From this point forward, from 1978 through the eighties, China initiated an opening up of its domestic economy as well as approaching the rest of the world with open arms.

The foundations were laid during the presidency of Richard Nixon. His key Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had laid the groundwork for this reform during Mao’s era while Mao was still alive. The proposition to China was that if China were to open up, the United States would accommodate China’s rise by opening up the American consumer marketplace to Chinese goods. This offered China an option, in other words, it came down to: who would you rather trade with? Would you rather trade with Soviet Russia, or would you rather trade with the Americans, who are rich? Given these two choices, China came to the wise conclusion that it is far better to trade with America than to trade with Soviet Russia, given the vastness and the deepness of the consumer marketplace in the United States.

EC: Although the trade war ceasefire reached at Geneva is already failing, both countries were initially willing to pause tariffs. Where do you think the countries will go next? You have observed that China has implemented policies that will position itself as the center of world trade. Does the United States feel threatened by those policies and what does the United States hope to achieve with such high tariffs if they are enforced?

AD: Yes, I think this is the big question. The April tariff was a religious moment for the global economy. It underscores the nature of the relationship between China and the United States. On the one hand, yes, the United States fears the industrial rise of China and the challenges it presents competitively to the United States. On the other hand, many parts and portions of the American industrial landscape have come to enjoy the benefits of doing business with China and sourcing its supplies as well as goods from China. Imposing a 145% tariff would mean iPhones would potentially be priced at $2,500. They would double in price. That’s a very vivid example; there are hundreds of thousands of other products that the United States and American companies import from China. It’s not just finished goods, but also a multitude of parts, components, and supplies that ultimately go into the American consumer landscape.

145% tariff would be, in my opinion, madness or MAED, mutually assured economic destruction. You don’t win in wars if you hurt your rival but kill yourself at the same time. This is an extremely dangerous game, and however much there has been a delinking over the past six years or more between the United States and China, important linkages still exist. The American industry would be confronting much higher prices regarding its sources of supply and a huge amount of disruption in terms of its normal operations and its ability to price goods at competitive prices. So, this is a moment of pause that the United States and China have to, in a sense, acknowledge. Both sides have to come to the bargaining table and discuss the key issues that separate the United States and China. Those key fault line issues are at the heart of this economic debate.

EC: As a veteran in both higher education and corporate America, you talked about the tariffs’ impact on American consumers and businesses. What advice would you give to American investors who are looking to invest in China?

AD: I’ve been advising American companies for the greater part of the last 25 years. If I were advising an American company today that was considering entering the Chinese marketplace, I would advise them to enter with extreme caution. Now is not a good time to enter for several reasons.

The Chinese economy right now is confronting economic challenges on multiple fronts. One might say it’s a recession, but I would say that the present state of the Chinese economy goes beyond that. The challenges that are being confronted in China are coming from multiple fronts. First of all, we’ve got a real estate bubble that has finally burst and the amount of debt that is involved in terms of its banking sector, in terms of the property sector, whether it’s developers, whether it is all those sort of components of real estate that has been so overbuilt in China, while all of those chickens are coming home to roost. That means we’re talking about billions and billions of dollars of unsatisfied debt.

Number two, trade wars. A very significant component of China’s GDP has been its dependency on exports. The trade war has not only embroiled the United States but also other nations around the world. In particular, the wealthy, advanced Western nations have also erected trade barriers against China. So, China is confronting a situation where it’s finding greater and greater difficulty in its ability to export its way out of its problems.

Number three, rising unemployment within China. China’s employment picture is quite dismal at the moment. The official numbers around youth unemployment are around 24%, but anecdotal evidence suggests it is maybe close to 50%. Many of the laborers who were factory workers, either migrant workers or those who have come from the countryside to work in factories in Shanghai and Shenzhen, are now out of work as those factories are confronting either bankruptcy or factory closure.

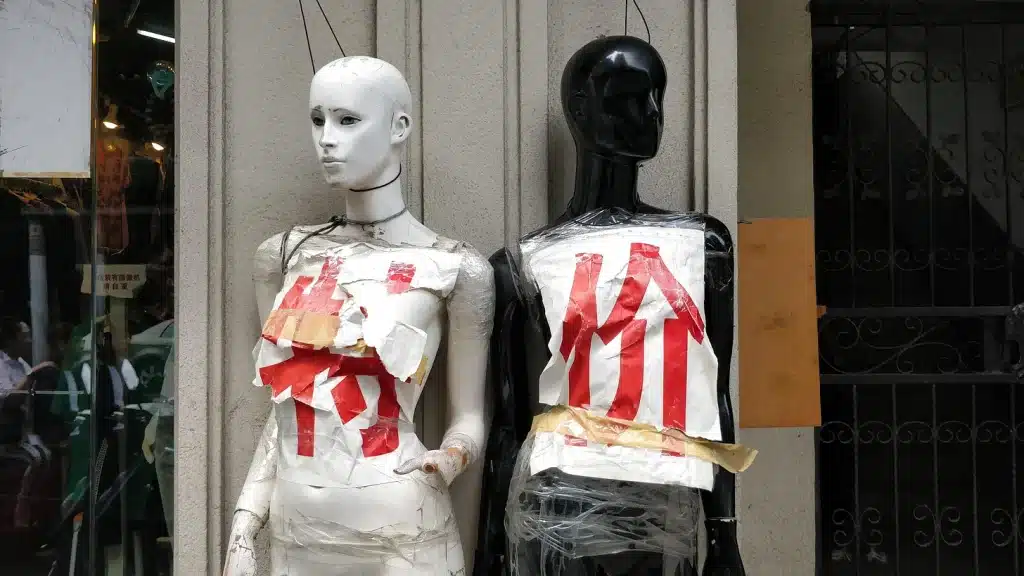

The consumer economy within China is now in a state of hibernation. Many small businesses that are related to either the retail sector or to services such as restaurants, dining, and entertainment, have cratered in China. There’s plenty of anecdotal evidence that many main streets in large cities in China, once vibrant and bustling shopping districts, are now eerily quiet. So, across all these dimensions, China is confronting a multitude of economic challenges.

As a result of that, I would urge an American company to proceed in China with extreme caution. Now is not the time to enter, albeit it would probably be a cheap time to enter, because many of those assets that you would need in order to invest in China have become incredibly cheap. You would be welcome with open arms in many of the great cities of China because of the reversal of investments on the part of America, a huge reversal of foreign direct investment into China.

Now’s not a time to enter China except for American businesses that are interested in distressed assets, meaning that they’re looking to go into China to acquire real estate or machinery cheaply. There’s a lot of machines and machine tools on the secondary market that are up for sale that are extraordinarily cheap. But if you’re looking to go to China to actually do business, it is probably not the best time.

EC: What about the Chinese companies that are coming into the United States, which President Trump has publicly supported?

AD: Many Chinese companies, both large and small, are extremely eager to come into the United States because, by positioning and putting operations in the United States, they can escape tariffs.

You don’t get an import tariff imposed on you if you’re manufacturing in the United States. Now, Trump has certainly made a lot of talk about encouraging all manner of foreign companies to come into the United States to create employment. But that largely extends to the traditional Western allies as well as Eastern allies of the United States. If a Chinese company is considering coming into the United States, I would again inform them that it will be an extremely difficult process to overcome. There’s a law in the United States called CFIUS, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States. It is a multi-agency review that involves upwards of 10 federal agencies, including the executive branch. You would have to clear Treasury, clear the U.S. Department of Commerce, clear the Pentagon, and clear the CIA. Any company whose origins or investors are from China would be subject to U.S. review.

The approval process is so onerous that anything even remotely related to national security would be automatically revoked. A case in point was the acquisition of Smithfield Farms. Smithfield Farms is a large pork producer in the United States. A Chinese agricultural company acquired Smithfield Farms. That acquisition took several years to get approved, and the last time I checked, I didn’t think that pork products or bacon represented a national security threat, but that just shows you how difficult it is that even an agricultural pork producer would have difficulty establishing itself or investing in the United States. This is not easy. I think many savvy and knowledgeable Chinese companies understand the difficulty of making that happen. We see that in the numbers. Foreign direct investment on the part of Chinese companies into the United States, even prior to the pandemic, has been at a steady decline. Today it’s almost non-existent.

EC: Could you provide an example of an American company you advised that had a significant economic interest in China, but is now facing critical decisions regarding the future of their business overseas?

AD: I can’t disclose some of the things I discussed with my clients, but an example is a very famous American company called Estee Lauder, one of the world’s two largest prestige beauty companies. They are one of the most successful global companies in beauty as well as skincare. Once China opened up in the eighties, the Estee Lauder family doubled down and decided it was the market of opportunity and the future of their company. So, for the past 30 or more years, Estee Lauder has made significant investments in expanding its reach into the Chinese marketplace, starting with first tier cities, and now in second and third tier cities.

It is a well-known brand, and I dare say that there are very few Chinese consumers who are not aware of their well-publicized brands as a result of their huge distributional reach into the Chinese marketplace. Estee Lauder is one of those companies that, right now, are hurting as a result of the pandemic. They are beginning to rethink how extensive they want their exposure to be in China. It’s a result of their China exposure that their stock price has declined by half as a result of a decline in sales within this marketplace that held so much profit. I believe that the company is rethinking its investments in China.

They will not abandon China. Certainly, you cannot abandon China, but I think perhaps they may be pulling back to a certain extent the aggressiveness with which they have been pursuing the Chinese market.

EC: Many American consumers and small businesses have also felt the pain of the new tariffs. In what ways can they advocate for themselves and factor into the discussions of the U.S.-China economic partnership? What is the role of small businesses in U.S.-China relations?

AD: The problem in America is that large companies and big businesses have a disproportionate voice on Capitol Hill. They have a disproportionate amount of political influence, whereas small businesses do not. To an extent, the April tariffs represented a death sentence to many small companies. The newspapers are full of stories about small retailers, maybe a fashion retailer selling women’s clothing or a small toy store that’s sourcing toys and other types of products from Chinese factories. There are even stories about the service sector, beauty salons, hair salons, and nail salons noticing an increase in prices for many of their disposable goods, such as nail files and other types of hair products, many of which come from China. They saw not only a shortage of those supplies, but an immediate decrease in these critical supplies that are used in these day-to-day service businesses that are the foundation of American small-town life. And so many small businesses and small industries were confronted with a potential death sentence as a result of the China tariffs.

Large companies like Apple not only have the resources, but they also have the capability of scouring the world and traveling all over the world to find alternate sources of supply. Small companies don’t have those resources. They simply don’t have the resources to say, you know what, I’m going to leave the United States for the next month and go travel around India and Vietnam looking for an alternate source of supply for nail files. So small businesses are stuck. They don’t have the resources to look for alternate supplies, whereas large companies do have those resources, which means the impact on small businesses is much greater and much larger. How is this going to be reflected? I would recommend waiting for the midterm elections. Small businesses constitute a very large segment of the American commercial landscape, and if they collectively voice their opinions and their displeasure at the polls, this will be a wake up call to the incumbent party and the president as to whether or not this aggressive trade policy is a wise decision in terms of its impact on the American commercial and business landscape.

EC: Switching gears, throughout your career in teaching business and trade, you have taught classes in different countries, and you took your American students on trips to countries including China. Speaking of the importance of students exploring U.S.-China relations through on-the-ground experience, could you share some of the memorable experiences from the recent past where you took students to explore China?

AD: My global experience has always been highly oversubscribed. One of the things I do ask the students who are coming is, have you ever traveled to Asia before? Have you ever been to China? Have you been to any of these places in East Asia? And the majority of them have never traveled to that part of the world. So, for them, it’s a very new experience. When I have an American student who’s never been to a place like China, one of the first things that they immediately sense is that what they read about in American media, either in mass media or newspapers, often contradicts what they see on the ground.

The first thing they acknowledge is the enormity of the Chinese population and the rapid growth. It is perceptible, and it is visceral. You can sense the energy. You can sense the overall economic vibrancy the minute you set foot in China. I have taken students to both Shanghai and Beijing, and they were simply in awe of the level of development that they were witnessing. They noticed better mass transit than that which can be found in the United States, cities that are gleaming with skyscrapers and vibrant shopping malls, and street life. All of these experiences are invaluable and have led to transformative thinking about what they’ve seen and what they’ve witnessed. Also, the students have expressed a desire to visit these regions on a more regular basis, if not even find a way to work there.

EC: In 2020, you had an interview with Mike Walter of CGTN, in which you said you took your students on trips to China to provide them a fresh view on trade with China. You proved to be ahead of the curve as President Xi announced in 2023 that China is inviting 50,000 foreign students for exchange in the next five years. Do you think that young people can provide a new perspective on U.S.-China trade policies and facilitate robust economic conversations?

AD: Again, there is no substitute for on-the-ground experience and intercultural exchange. I do agree that educational diplomacy has to be a part of any diplomatic toolkit. We have what we call formal diplomacy, which is the exchange of embassies, heads of state, and ambassadors, having official diplomatic outposts in countries, like attendance at international forums such as the World Trade Conference. But educational diplomacy is just as important because if you can welcome 50,000 foreign students from different countries, including America, to spend an educational experience in China, however short or long, that encounter will certainly transform the way people think about China. Those students and young people will return to their countries and articulate a view that might be contradictory to the mainstream views of places like China.

For any diplomatic strategy, it not only involves formal diplomacy, but it also involves things such as food diplomacy as well as educational diplomacy. Food diplomacy, by the way, is one of the ways you can express and extend an understanding of different cultures. By finding ways to export your food or encouraging either Chinese chefs or Chinese entrepreneurs to share the culinary heritage of Chinese cuisine with other nations, you get Americans or others to appreciate culture through food. The Europeans have done this extremely well. There isn’t a nation on the face of the earth that doesn’t like pizza. That’s a testament to Italian food diplomacy and how they do this extremely well. For China as well as, places like Thailand and Japan, they are starting to think carefully about how that is a component of their diplomatic efforts to spread soft power and to change perceptions around the world.

For the United States, Hollywood and our music industry are arms of American cultural diplomacy. Some might even argue it’s cultural imperialism because, in a sense, irrespective of the culture, youth around the world know all the lyrics of Taylor Swift songs, and can sing them word by word in English, even though they don’t speak English otherwise. So yeah, this is an important element, but the problem is there’s no return on investment with these other kinds of diplomacy. Let’s say you sign a trade agreement, you can have a definable return on investment: you signed a trade agreement and now you have $500 billions of trade that you have both agreed to, committed to.

There’s a less tangible return on investment with things like cultural diplomacy and food diplomacy, meaning that the outcomes are hard and difficult to measure. Nonetheless, we know that they do exist because if you look around the world at how young people dress, at the kinds of music they listen to, and at the entertainment that they appreciate, it is to the benefit of America. This has been very successful even in China. When I go to China and I see a young Chinese person wearing hip hop clothing and trying to emulate the styles of hip hop rap masters, that tells you about the power of American cultural diplomacy. Hard to measure, but certainly tangible to the extent that it’s observable.

Edison Chen is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and studies Public Policy at Duke University.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.