Remembering Joseph Fewsmith: The Passing of a Generation of China Hands

Africa and the U.S.-China Rivalry w/ Maria Repnikova

- Interviews

Kelly Zhuang

Kelly Zhuang- 05/27/2025

- 0

Dr. Maria Repnikova is an Associate Professor in Global Communication at Georgia State University. This year she is also a non-residential Wilson China Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center for Scholars. She received her doctorate (DPhil) in Politics at the University of Oxford where she was a Rhodes Scholar. She is a scholar of China’s political communication and speaks fluent Mandarin, Russian and Spanish. Her research specializations include media-state relations in China, including political persuasion and critical journalism; Chinese soft power and public diplomacy, especially in the African context; and China-Russia comparisons.

Kelly Zhuang: In your article on digital diplomacy, you introduce the concept of “asymmetrical discursive competition.” What does this term mean, and why is it important for understanding China–U.S. engagement in Africa?

Maria Repnikova: This concept was developed with my graduate student by looking at China-U.S. narratives, specifically the competition for narratives on social media. We analyzed embassy communication from selected Chinese and American embassies, focusing on how they referenced each other when addressing African audiences. We looked at whether they mentioned one another while communicating their policies or outreach to African publics on Twitter.

We found that Chinese diplomatic accounts were quite active in launching discursive attacks, both defensive and offensive, against the United States. They invoked the U.S. not constantly, but fairly routinely, bringing it up in relation to both Africa engagement and broader global affairs. In contrast, U.S. accounts tended to ignore China. Surprisingly, we didn’t see many discursive attacks, defensive, offensive, or otherwise. China seemed largely absent from U.S. embassy communications. Instead, the focus was on promoting U.S. initiatives and engaging African audiences, often by amplifying African voices.

This highlighted an interesting imbalance. Chinese embassies appeared more actively involved in narrative battles with the U.S. in Africa, whereas U.S. embassies were more disengaged. That’s somewhat counterintuitive, given that the dominant narrative in Washington, especially before Trump’s re-election campaign, portrayed China’s actions in Africa negatively, using terms like “debt trap diplomacy.” But what’s said in Washington doesn’t always align with what’s communicated on the ground. In African countries, U.S. diplomatic messaging appears more subtle, rarely referencing China, and instead emphasizing U.S.-Africa relations. Meanwhile, Chinese embassies seem more assertive and frequently invoke the U.S.

In sum, China seems more invested in using Africa as a platform for global narrative competition with the U.S., while the U.S. appears more reserved, if not absent, from that specific contest, at least in its public diplomacy.

KZ: Building on that, what explains the difference in engagement styles between Chinese and U.S. diplomatic messaging in Africa, particularly on platforms like Twitter?

MR: One important qualifier is that the majority of messaging by Chinese diplomats on Twitter is still fairly reserved. Most of it focuses on promoting China, its interests, its diplomacy, and its accomplishments, both within Africa and globally. So the dominant theme remains centered on presenting a positive image of China.

What stood out, though, was the pattern around direct references to the United States. Chinese diplomatic accounts were more likely to invoke the United States and often did so in a critical or provocative way. In contrast, the United States accounts generally did not mention China at all. The United States’ messaging seemed more focused on engaging African audiences directly, without entering into a rhetorical back-and-forth.

One possible explanation for this difference is the rise of what is often described as wolf warrior diplomacy in Chinese social media communication. Some diplomats, in particular, have adopted a more assertive and confrontational style, which may be shaping the tone of their online presence.

Another reason could be how Africa is perceived within each country’s broader diplomatic strategy. For China, Africa often serves as a space to legitimize its global position and to contrast itself with the United States. Chinese diplomats may see African platforms as a place to highlight the United States’ shortcomings and assert China’s comparative strengths. On the other hand, the United States may not view Africa in the same way as a space for direct geopolitical messaging aimed at countering China. Because of this difference in strategic vision, the communication styles diverge significantly.

KZ: Given China’s frequent use of Africa as a rhetorical proxy in global legitimacy battles with the United States, what are the risks and potential benefits of African countries being instrumentalized in this great power rivalry?

MR: In terms of risks, some of the narratives we analyzed on Twitter didn’t really engage directly with African audiences. The messaging was more focused on discussing the U.S. or presenting negative portrayals of it. The risk here is that African countries might be used primarily as a rhetorical tool to legitimize China or its interests, without necessarily receiving the benefits or being meaningfully engaged.

That said, there are also clear benefits to having multiple global actors involved. It’s not just the U.S. and China anymore. European countries, along with newer players like Turkey and Saudi Arabia, are also actively communicating and promoting their influence in Africa through both soft and hard power. This broader interest allows African states to negotiate better deals, assert more geopolitical relevance, and attract more investment. It also gives them greater room to shape engagement in areas like media diplomacy, education, and other soft power sectors where international interest is growing.

While the risks of being caught in a kind of proxy competition or rhetorical contest are real, and can sometimes feel destabilizing or unfair, they are difficult to avoid. Given that, it becomes important to take advantage of the interest from various parties. In this context, African elites have emerged as particularly active negotiators, strategic thinkers, and flexible actors who are skilled at navigating the interests of major global powers such as China and the United States.

KZ: In the context of rising tensions between major powers, particularly in the form of discursive and proxy competition, what are some concrete ways African countries can engage to enhance their agency and influence moving forward?

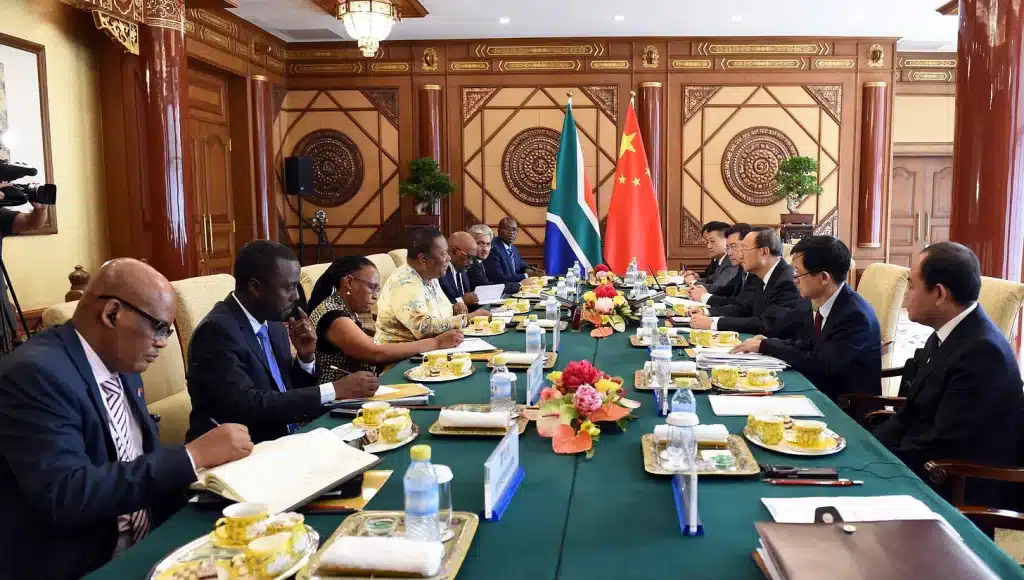

MR: I think African actors are already showcasing a great deal of agency. They often hold simultaneous meetings with different leaders and visiting delegations. They negotiate contracts across various forms of capital, whether Western, Chinese, or others. Increasingly, we’re seeing competitive bids for deals, rather than default alignment with a single power. This demonstrates diverse forms of negotiation and agency, from top-level government officials to bottom-up actors like traders, migrants, and everyday people who engage with Chinese, American, and other foreign counterparts to pursue different benefits and agreements.

So, the agency is clearly already present. What is often missing, though, is the infrastructure for knowledge production about the foreign powers they’re engaging with, especially China. There is a lack of immersive education and deep knowledge about China’s economy, politics, and how to effectively negotiate with Chinese actors. While Chinese language training is available through Confucius Institutes, it doesn’t compare to the kind of knowledge infrastructure the U.S. has had about China.

In the U.S., at least until recently, there has been extensive China-focused scholarship across universities. Many officials have studied the language, lived in China, and developed significant expertise. But in many African countries, such expertise is still sparse. In Ethiopia, where I conducted research, I found very few independent China experts. Many of those who did exist had been trained or sponsored by China, often through Confucius Institutes, which can make it harder to cultivate a fully independent perspective.

Stronger negotiation outcomes would depend on building deeper knowledge about China, its goals, its interests in Africa, and its strategic motivations. This requires significant investment in training, language acquisition, and expert development. But that’s a big challenge. Training China specialists is expensive, and it’s difficult to find qualified professors, materials, and institutional support. On top of that, because of high unemployment rates in many African countries, students tend to focus on learning skills that can immediately translate into jobs. Becoming a China expert often doesn’t lead to direct employment, especially within government structures, which makes it a less attractive path.

As a result, there are very few independent China-focused centers or academic initiatives within African universities. So while there’s a clear opportunity to build local expertise and capacity, actually realizing that potential remains a significant challenge. That’s one point I wanted to emphasize from my fieldwork.

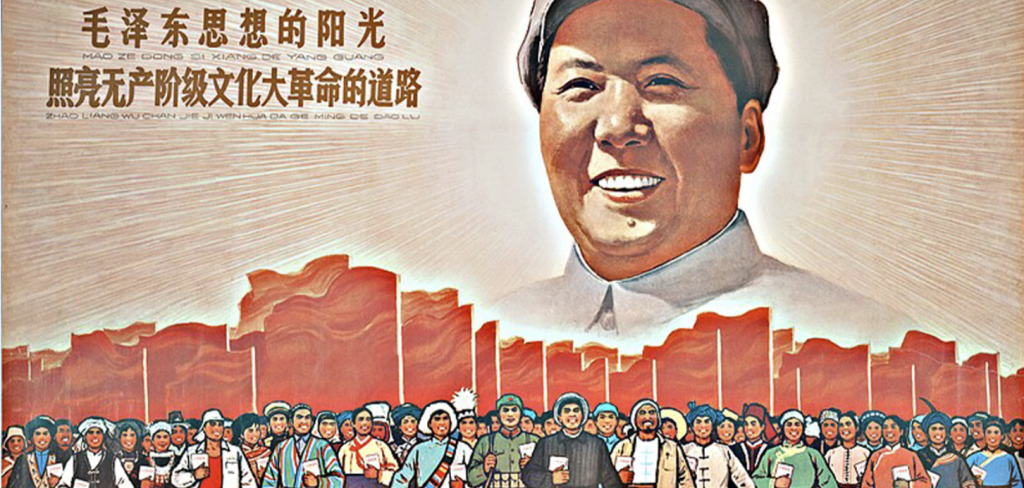

KZ: You describe the Confucius Institute in Ethiopia as a case of “pragmatic enticement,” offering more than just language and culture. For those unfamiliar with the initiative, could you explain what Confucius Institutes are, their stated goals, and why they’ve become such a focal point in global debates about China’s soft power?

MR: Yes, the Confucius Institutes primarily focus on Chinese language training, though they also organize some cultural events, mostly centered around traditional Chinese culture rather than modern or contemporary aspects. Originally, they were fully sponsored and managed by the Chinese state through the Ministry of Education, under the Hanban agency. However, in recent years, these institutes have faced significant pushback in the West, particularly in the United States, but also in countries like Canada, Australia, and across Western Europe.

Critics accused them of spreading ideological influence, propaganda, and censorship. As a result, many were shut down. Interestingly, the U.S. once had the highest number of Confucius Institutes globally, which reflects how central it was to China’s soft power strategy. Whether or not we consider them a failure, the initiative has largely disappeared in the U.S., with most of the institutes having closed.

In response to this controversy, the Chinese government restructured the institutes. They are now managed under a government-led NGO setup, which is intended to make them appear more independent and less state-controlled. While many participants remain government-affiliated, the new structure is positioned as a civil society initiative. Despite these changes, the core mission remains the same: teaching the Chinese language and promoting cultural exchange.

In contrast to the West, Confucius Institutes in Africa remain quite active. There have been no widespread closures, and many programs continue to operate vibrantly. Some African educators and policymakers have expressed skepticism and a lack of full trust toward the institutes, as seen in several published articles. However, this hasn’t translated into large-scale rejection or shutdowns.

One of the unique features of Confucius Institutes is that they are embedded within local institutions, typically universities or high schools, rather than operating as standalone cultural centers like the Alliance Française or German Goethe-Institutes. This means they are physically and institutionally integrated into local campuses. Their staff usually includes volunteer teachers, often recent university graduates from China, along with more experienced directors or professors who are sent to teach for extended periods. These teachers provide beginner to intermediate Chinese language instruction. The most dedicated or high-performing students often receive scholarships to study in China for a summer, a semester, or even a full academic year. Many students benefit from these opportunities, but the primary draw, especially in countries like Ethiopia, where many Chinese companies are operating, is employment.

The institutes not only provide language training but also actively facilitate job placement. They organize events where Chinese company representatives are invited to campuses, and sometimes they take students to the company headquarters. In some cases, interviews are even conducted within classrooms. This creates strong networking opportunities. Based on my research, translator positions typically pay around $500 per month, which is considered a relatively high salary in Ethiopia, two to three times the salary of a university professor.

However, this relationship is quite transactional. If job opportunities disappear, for example, if Chinese companies leave or stop hiring translators, then the institutes risk being closed. Several university deans I interviewed in Ethiopia mentioned they would discontinue the institute if it no longer led to employment. The main value of these programs is seen in their practical outcomes. If they stop producing jobs, their relevance fades.

So, the dynamics in Africa differ significantly from those in the West. In the U.S., closures were largely driven by ideological concerns, fears of political interference, and censorship. In Ethiopia and other African countries, the question is more pragmatic: Are these institutes useful? Do they prepare students for the job market? If the answer becomes no, their future is uncertain. This creates both opportunity and fragility. The success of these institutes depends heavily on whether they continue to meet local needs, especially in terms of employment.

KZ: Do you see initiatives like the Belt and Road infrastructure projects and the Confucius Institutes as working in parallel? For example, while infrastructure investments may generate jobs and economic opportunities, are the Confucius Institutes complementing those efforts by equipping African populations with soft skills such as language and cultural knowledge?

MR: I didn’t hear about them going together in this very carefully planned way. The BRI and the Institute seem to be kind of separate initiatives, but at the same time, they’re entwined. Because if you have the BRI, if you have those projects, then you also have more interest in the Chinese language. There’s more room for engagement. But I think overall, when we think about China’s global engagement, or China’s engagement outside its borders, the economic side or the economic aspect started first. The BRI is the big label and the big kind of manifestation of that. But China has been very active in Africa for at least a decade, if not two decades, arguably already very active. So the economic aspect started first, and presently, the cultural soft power facets have become more visible.

It seems that the Chinese state and various institutions decided that more diplomacy was needed in Africa, in part because the economic engagement attracted a lot of scrutiny from the West. A lot of Western media started writing about debt traps, neocolonialism, imperialism, labor practices, and cheap and low-quality goods. Just all kinds of critical articles and content started to come out. And that was quite unpleasant and irritating for the Chinese side. They were doing all these things and receiving really bad press. So the question became, how can we change hearts and minds? I think the initial idea was that they needed to do something more on the softer side, to create more affinities, to build relationships, to foster pro-China sentiments. But then, part of that effort became a question of how to attract people to these softer engagements. The answer was to offer something practical, job promises. It was a way to incentivize and attract people to study Chinese.

KZ: What are some other major institutes or initiatives in Africa, from either the United States or China, that focus on soft power engagement?

MR: One of the major areas of soft power engagement is the media. Chinese media have been very active across the African continent. Most of it is state-owned, including outlets like China Global Television Network, China Daily, China Radio International, and Xinhua News Agency. While many of these operate primarily out of Nairobi, they also have branches in numerous countries throughout Africa. This media presence represents a significant form of engagement.

There has been some competition from Western media, particularly the BBC and CNN. Voice of America used to be a major player, but that presence has been significantly reduced, especially after being shut down under the Trump administration. So, at least for now, that particular form of competition appears to have paused.

Beyond state media, there are also nonstate actors that play a role in soft power outreach. One example is a Chinese company that provides access to digital television. I am blanking on the name at the moment, but it is easy to find. While the company is technically nonstate, it has close ties to the Chinese government. Similarly, Huawei has provided internet access and also plays a role in training engineers across Africa. These are soft power initiatives as well, just coming from corporate rather than official diplomatic channels.

Education is another major area. In addition to the Confucius Institutes, there are numerous fellowships and training programs. Thousands of African officials and journalists have been trained in China. These programs are often facilitated by Chinese embassies but involve a wide range of actors once participants arrive in China, from universities to media institutions to local and provincial governments. These visits offer exposure to different parts of Chinese society and serve as a powerful channel of influence.

The United States has had similar efforts, though on a smaller scale. For example, the Mandela Washington Fellowship under the Young African Leaders Initiative and other State Department programs have brought journalists, civil society actors, and business professionals to the United States for leadership exchanges. However, the numbers are significantly smaller, more in the hundreds compared to the thousands supported by China. While the intent is similar, exposure, relationship building, and influence, the current administration in Washington has scaled back much of this programming. As a result, it is unclear how much of this will continue. If these trends persist, China may increasingly become the dominant player in educational diplomacy on the continent.

KZ: How have China’s defensive narratives and the differing approaches of Chinese and U.S. embassies in engaging with African publics shaped African perceptions of both countries? Have these communication strategies had any noticeable impact on how African populations view China and the United States?

MR: Perceptions are always somewhat difficult to measure. While we have public opinion polls and perception indexes, it’s not always clear what those perceptions are actually tied to. Are they shaped by specific engagements on the ground, or do they stem from preexisting ideas and assumptions? The Afrobarometer is one of the main polling sources we have regarding African views of China. According to its findings, perceptions of China across many African countries tend to be more positive than negative, suggesting that China’s outreach efforts may be having a favorable impact.

However, when it comes to questions like which development model African publics prefer, China’s or the United States’, the U.S. still tends to come out on top in most of the countries surveyed. That makes things more complex. It raises questions about what “development model” really means to respondents and how people interpret that idea. But at the very least, in these more foundational questions, the U.S. often ranks higher or at least very close to China.

That said, much more research is needed to understand how these dual perceptions evolve over time. A recent study comparing the impact of foreign aid from China and the United States found that China gains very little in terms of public opinion, while the U.S. tends to benefit significantly. U.S. aid has historically helped foster positive perceptions and a sense of affinity, particularly through programs like USAID and the CDC, which have been influential in areas like public health and disease control.

But it’s important to consider the broader political context. In recent years, the U.S. government has shifted direction, and many of these long-standing diplomatic institutions have been weakened or dismantled. As a result, the U.S. has become less visible in parts of Africa, which may in turn affect how it is perceived. If the U.S. becomes less present, it may also become less favorable in the eyes of African publics. In contrast, China could gain ground simply by remaining active and visible.

So even though we do have polling data and perception indexes, they only capture part of the picture. We’re living through a period of transition, and it wouldn’t be surprising if public attitudes shift in response to changing visibility and engagement from both powers.

KZ: Do you think African countries are primarily guided by pragmatic interests in their diplomatic and educational engagements, rather than aligning strictly with one development model? Is it more likely that they adopt mixed elements from both China and the United States, while keeping practical benefits as their top priority?

MR: I think pragmatic interests are really at the heart of it. It comes down to practical and tangible gains, what you actually get out of an engagement, whether that’s resources, opportunities, or support. That’s what drives a lot of these negotiations. And especially now, with the United States shifting so quickly, particularly in terms of its external presence and diplomacy shrinking, I think those practical offerings matter even more. In the past, you could say the United States stood for certain values or ideals, and maybe that had a long-term impact, or at least it carried a kind of political vision that some found meaningful.

But now that this isn’t really the case anymore, I think it’s becoming more important for countries, especially recipients, to look at what is actually being offered. What is on the table right now matters more than broad ideas or promises. The United States, at least for the moment, is not projecting those values the way it used to. So in that sense, yes, pragmatic interests seem to be the main priority.

KZ: Given the uncertainty surrounding the future of U.S.-China rivalry, do you think the United States will seek to increase its own presence and influence in the Global South, or will its efforts primarily focus on diminishing China’s impact in the region?

MR: At the moment, it seems unlikely that the United States will become more active in a meaningful or constructive way. The current direction of U.S. foreign policy appears to be quite U.S.-centric and inward-looking, with a strong focus on combative measures like tariff wars and pressuring other countries to yield to American demands. Diplomacy itself is being questioned or sidelined by the administration. This applies not only to U.S. competitors like China and Russia, but also to traditional allies such as Western European countries and Canada. The overall approach is more about provocation than engagement.

I think this kind of posture is unhelpful and will have long-term repercussions. It is difficult to see how the U.S. can project power and simultaneously position itself as a credible diplomatic actor in the Global South. Resources for diplomacy are being cut. The State Department is shrinking, and many engagements are more coercive than cooperative. Even countries in the Global South are facing tariffs and trade restrictions, which directly affect how the U.S. is perceived.

That said, I do believe that on the ground, within U.S. embassies, there are still professionals who remain committed to their work. They will continue carrying out their missions and engaging with local communities. So not everything is disappearing. There are still people dedicated to diplomacy and foreign service who will try to sustain relationships where they can. But in terms of expanding U.S. influence or strengthening its presence in a substantial way, especially during this political moment, it is very difficult to imagine that happening. The broader environment simply does not support it.

KZ: Looking ahead, given that African actors already demonstrate agency, how do you see them moving forward in shaping the discursive space around global engagement?

MR: They are already very active drivers when it comes to communicating, engaging, and initiating many of these efforts. Even with Confucius Institutes, a lot of the initial steps were taken by the local side. It was not simply China coming in and saying, “Here is a Confucius Institute.” Maybe the first few were more driven by China, but the expansion was often led by local institutions. Local universities actively requested more Confucius Institutes and classrooms because they saw them as beneficial for employment opportunities and student development.

So many of these initiatives, from the start, have been shaped mutually. It is not just China imposing something or acting unilaterally. The same applies to BRI and other infrastructure projects. In many cases, it is the local governments that request these investments.

When I spoke with African students in Ethiopia about China-Ethiopia relations, about who benefits more and how these relationships are formed, they often pointed to their own government. They raised concerns about the lack of transparency, saying their government is initiating engagements but not being open with the public about the terms, the loans, or the risks involved.

So a lot of this also ties into domestic politics. It is not just about whether China is driving something, but also how much local governments are disclosing to their own citizens. In that sense, these governments are clearly active in initiating and asking for more investments and deals. They are very active drivers. The question is not whether they are active, but what kind of drivers they are. Are they transparent? Are they negotiating from an equal position? Are they equipped to get a fair share? Those are the questions I will be paying more attention to moving forward.

Kelly Zhuang is an intern at The Carter Center’s China Focus initiative.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.