Biden’s Bloc Party is Over. Stop it.

- Opinion

Henry O'Connor

Henry O'Connor  Nick Zeller

Nick Zeller- 04/29/2025

- 0

Not all people exist in the same Now. They do so only externally, by virtue of the fact that they may all be seen today. But that does not mean that they are living at the same time with others. Rather, they carry earlier things with them, things which are intricately involved. One has one’s times according to where one stands corporeally, above all in terms of classes.

Ernst Bloch (1935) The Heritage of Our Times

The Democratic establishment’s full-spectrum austerity program against new ideas has begun to shift from the frustrating to the genuinely bizarre. On the one hand, domestically, there remains a deep sense of anticipation for Trump’s supporters to be hit in the face by the rake they stepped on in November 2024. This is both a willful misunderstanding of the enjoyment MAGA gets from watching others be hit by the same rake and an expression of the liberal impulse to blame voters for abandoning the Democrats instead of asking if things might be the other way round.

On the other hand, internationally, although it is clear that the second Trump term has already permanently changed the faltering world order that preceded it, the mainstream Democrat-aligned commentariat continues to advance the idea that (somehow) the United States can and should maintain its role as global hegemon through X, Y, and Z steps that will exclude China from world trade, encircle it militarily, and spark economic rejuvenation back home.

There are obvious dangers in the continued Washington consensus that China is somewhere between rival and enemy and must, no matter the label, be economically overcome. The Biden administration was happy to expand most of the first Trump administration’s adversarial policies toward China. The current Trump administration, after rattling the cage of every U.S. ally, has launched its trade war with China in earnest. Foreign policy, however, is an extension of domestic policy and a symptom of social pathologies back home. If there is a throughline of U.S. China policy for the last decade, it is American leaders’ willingness to risk violence between two nuclear powers if that’s what it takes to avoid improving the everyday lives of Americans by creating a reasonable social safety net.

This last point may be the only explanation for the publication of an otherwise completely anachronistic article by Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi, both members of the Biden administration working on China and the Indo-Pacific, in Foreign Affairs. The basic argument is for a “capacity-centric statecraft” led by the United States in which “the United States and its partners must play for cohesion and collective leverage” to combat China’s key purported advantage – its scale.

By scale, they mean, quite literally, that China is big and makes efficient use of its resources. Given the right changes in China’s domestic economic policies, large internal markets could make it less reliant on international trade and give its firms an unfair advantage over the United States. (The enemy is always getting away with something.) Scale, according to the authors, accounts for how Germany and the United States surpassed British steel production in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and is cause for alarm in China now. The article makes only passing mention of British colonialism or the tendency of developed capitalist economies to move up the commodity chain, producing more technically refined commodities for sale in less developed economies. The United States was happy to allow Japanese tariffs against American cars if American companies sold automotive manufacturing equipment to Japan.

The questionable political economy, however, is not the confusing part. The confusing part is this: What in the world are Campbell and Doshi talking about when they talk about a “coherent and interoperable bloc, with the United States at its core”? Who are these partners still willing to be led by the United States?

Recently, The Monitor published an article by Jessica DiCarlo et al. arguing that the borders of the new Cold War would be the contours of each sides’ supply chains. Campbell and Doshi elevate this position from implication to explicit policy proposal, but they do so when there is vanishingly little sense to be made of a U.S.-led anything. The class of intellectuals that ought to be at the cutting edge of ‘progress’ against the backward-looking horde (great again) is now itself looking backward. The aim is to revitalize the recently failed Biden administration attempt at Cold-War-but-it’s-about-AI-and-batteries bloc building. It is completely out of time.

Tatters of the Old Order

The current American administration is threatening conquest of NATO allies, harassing former territories, launching a tariff war that endangers global supply chains, pulling life-saving aid from countries that desperately need it, and plummeting American democracy to new depths. The United States’s soft power is in shambles, its allies no longer feel able to rely on it, and China has been on a tour to rally economic support from Japan, South Korea, Sweden, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and the EU since Trump took office. The White House has opened up a new chapter in US-China-World relations and simply suggesting a foreign policy shift from command-and-control diplomacy to a new capacity-centric statecraft fundamentally ignores the present, the past, and any reasonable suggestion of the future, a future that no longer orbits the United States.

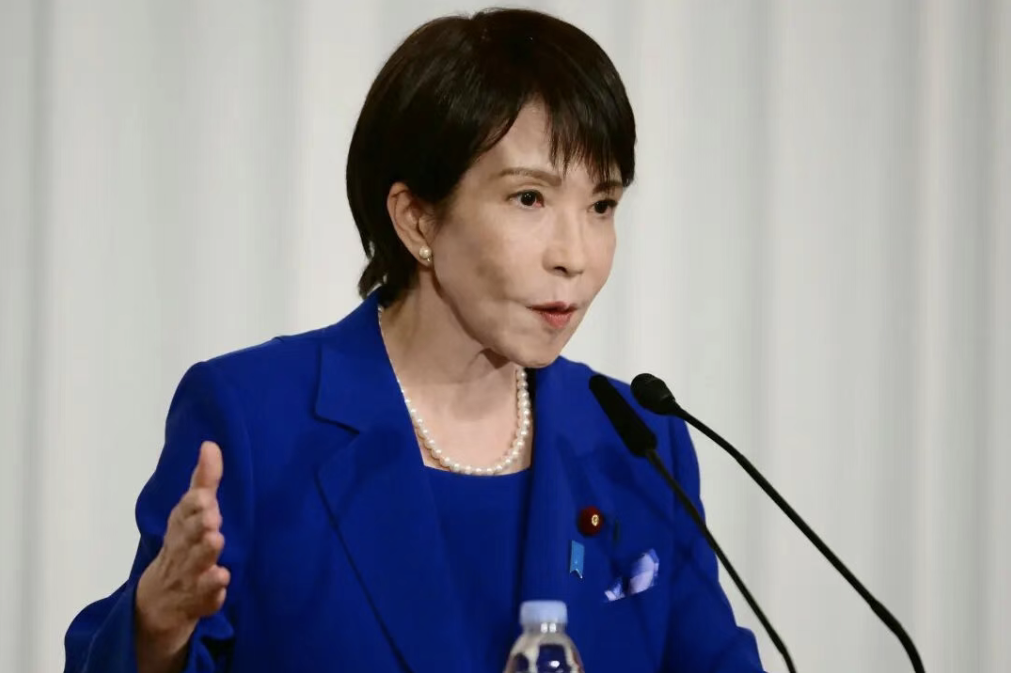

The European Commission, now reportedly issuing burner electronics to its U.S.-bound staffers, has reopened talks with Australia on an EU-Australia free trade deal. Japan, whose Prime Minister, Shigeru Ishiba, ruled out big concessions on trade to the Trump administration, held a joint summit with South Korea and China on speeding up talks on a trilateral free trade agreement. Japan, amidst the backdrop of Trump criticizing the U.S.-Japan defense pact as “one-sided”, issued a joint media statement with the U.S.’s greatest strategic competitor, China, to reaffirm their commitment to free trade and “a free, open, fair… and predictable trade and investment environment.” Some of the United States’s closest allies are building supply chains and economic ties specifically meant to bypass it. The U.S. may very well have a participatory role to play in these supply chains in the future, but it will be a far cry from hegemonic bloc leadership.

In the meantime, Chinese President Xi Jinping is kicking off his tour of Southeast Asia in Hanoi with the Communist Party of Vietnam’s General Secretary To Lam and a flurry of 45 agreements covering supply chains, rail, AI, cultural exchange, and more: areas critical to both countries’ security interests. While planned since before Trump’s tariff announcements, the visit coincides with Trump labellingVietnam as the “single worst abuser of anybody” and has since described the meeting as a plan to “screw” the United States.

In 2023, Joe Biden visited Hanoi and elevated relations with Vietnam to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, a status equal to China and Russia in Vietnam’s eyes. However, in Xi’s own words, this most recent visit during Trump 2.0 was a “turning point of history.” The Chinese president also remarked on the necessity to “resolutely safeguard the multilateral trading system” and reiterated that a “trade war and tariff war will produce no winner,” a sentiment echoed at the previously mentioned South Korea-China-Japan summit by all three parties.

The tour continues with a visit to Malaysia. President Xi met with Malaysian Prime Minister Anway Ibrahim in Kala Lumpur and has since signed 31 new cooperation agreements covering everything from global security to artificial intelligence with China in the face of tariffs from the Trump administration. This comes after the Prime Minister invited President Xi to attend the 2025 ASEAN Summit during a working visit in November of 2024. Amidst all this cooperation, where is the United States?

For many years, in China, Trump has been ironically known as Trump the Nation Builder or Comrade Nation Builder, a naming tradition characteristic of Chinese netizens for his great contributions to the Chinese nation. He received the nickname shortly after the United States launched its first foray into trade war in 2018, resulting in billions of dollars of lost GDP and a $27 billion dollar bail out to American farmers devastated by his policy. Given the current trade conflict, it would be apt to rename him Trump the Bloc Builder for tossing the American buck to the world. The point isn’t that the United States will be forever isolated but that it has now destroyed the world it largely sought to build. Likewise, China’s attempts to be seen as the guarantor of free trade and globalization raise their own set of serious questions. What is obvious, however, is that the old system is collapsing.

Old Ideas for New Times

In the midst of this outbreak of trade deals and bilateral cooperation that bypasses U.S. interests, the article suggests the U.S. adopt a “deputy sheriff” system with partners that the United States defers to on matters of regional stability or countering China’s influence, namely Australia, Vietnam and Nigeria. How can we possibly “deputize” nations that are day by day closing ranks with China on the single largest predictor of aligned interests – economic cooperation? This argument not only ignores U.S. strategic interests but ignores the seismic rug pull that has yanked the order out from beneath Washington’s feet. Neither Washington’s strategic nor ideological interests align with the national security priorities of regional actors, and those regional actors’ priorities may not align with the region. How does a world of more heavily armed “deputy sheriffs” create a safer, more stable order?

They also mention that “the United States needs to construct what the historian Arthur Herman has called an Arsenal of Democracies: a networked defense industrial base built on joint production, shared innovation, and integrated supply chains.” The description of such a system curiously lacks a mention of shared democratic values. It is telling. The phrase itself – Arsenal of Democracies – is oxymoronic.

This proposal tacitly acknowledges that our system of values is not a factor in our strategic alliances and interests. Championing an Arsenal of Democracies and proposing Vietnam as a key ally holds two mutually contradictory truths. Firstly, that building an alliance of democracies is a serious United States foreign policy goal, and second that Vietnam, a country whose human rights record is described as “dire in virtually all areas” by Human Rights Watch, could be a deputy sheriff in a democratically aligned system. Either the Arsenal of Democracies is not about democracy, or Vietnam is now a democracy; the answer should be clear.

Even more striking is that one such proposed security ally, Indonesia, received $16.3 billion in foreign direct investment from China and Hong Kong, while the United States only provided $3.7 billion according to the Indonesian Investment Ministry. This proposal is deeply rooted in the misguided assumption of only America being a major player, that only the United States is capable of supplying weapons to Indonesia and that their purchase of our guns will indelibly bind us together in ideology and strategic interest. Indonesia receives four times more investment from China than from the United States and as it expands and grows into its population and strategic geography, it will not only have the United States to look to for security.

Rather than arms dealing, tighter integration, burden sharing, and conflict deterrence has been facilitated for the most part in the 20th century by tightly interwoven economic links. When the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to the European Union, was founded after World War II to bind French and German coal and steel production together, Robert Schuman, the French foreign minister declared it would make war between the two “not only unthinkable, but materially impossible.” It is unclear if arms sales can contribute to as stable system as broad-spectrum economic cooperation already has; weapon sales can turn on a dime, economic disentanglement is measured in a far larger time scale.

Common markets, with free movement of goods, and fair-trade practices have been the bedrock for the development of peace for nearly a hundred years, not only between allies, but especially between rivals. These markets have also produced profound inequality between nations, which is something a new system should hopefully address. The relative peace that comes from interdependence, however, should not be lost. Campbell and Doshi’s proposal for U.S. allies to “pool their markets behind a shared tariff or regulatory wall erected against China” flies in the face of everything that was learned in the failure of post-World War I policy and the success of post-World War II reconstruction, a period more peaceful than any other in Western history. How, as the article argues, would coordinated sanctions and export controls against China “function as a platform for deterring military aggression.” Did Biden hitting the big red SWIFT button against Russia deter the war in Ukraine? Did a coordinated economic assault on Germany’s fallen second Reich stop it from forming a third? If anything, Campbell and Doshi’s romantic appeal to the Biden bloc dream advocates a system of fewer connections between the world’s major powers allowing a radically higher likelihood for war between, again, nuclear powers.

During his visit to Malaysia on the 16th, Xi announced both sides must “combat the undercurrents of geopolitical and camp-based confrontation” while proposing ambitious deals to expand BRI across Southeast Asia. While China promises economic investment and increased bilateral trade, the apparent old-guard U.S. proposal is Korean weapons in Europe, Norwegian and Swedish missiles in Thailand, and a fortress that “Beijing cannot ignore” in the Andaman Islands. To neglect the bedrock economic development of these nations ignores their core interests and isolates the United States from some of the fastest growing and most dynamic markets in the world.

Realizing Campbell and Doshi’s ideas would not only expedite their warning that “the United States could find itself in the position of the United Kingdom a century ago,” but also ignores the century of policy that has allowed the United States to endure crises more effectively than nearly any other nation. It is not Washington’s status as an arms dealer that has kept it on top, but its stability, market, and deep institutional roots in the global economic core. (Although, arms dealing hasn’t hurt.)

Much of this needs to be rethought now that the United States’ position in the world has so radically changed, but trying to maintain Washington’s previous position only in a smaller, more heavily armed bloc is not a way forward.

Campbell and Doshi also urge the United States to learn from the lessons of the British empire and consider its failed attempts at “imperial integration” of its core territories, a statement that reveals both an underlying admission that the authors consider the United States an empire in the fullest sense and their idea that the United States should act in ways an imperial state was unwilling to, a stark contrast to the artifice of cooperation implied by their earlier assertion of the Arsenal of Democracies. One wonders how much longer until even the Democratic establishment will be forced to ask a question satirically raised by British comedian David Mitchell – “Are we the baddies?”

Despite an aesthetic of multilateral cooperation “with the United States at its core,” the multilateral solution endorsed is only achievable in a unilateral fashion. It is false multilateralism, the multilateralism of a colonial past, and the multilateralism of a hegemon over weaker nations. Such solutions presuppose a crumbling U.S.-led order and demands drastic actions against China by nations who have prospered thanks to their trade with it.

We Can Only Say What Isn’t Next

The only constant in American politics is that China is somewhere between a rival and the enemy and to contain China, we must export our domestic hysteria to states who gain more from their relationship with China than lose. U.S. proposals echo with Reagan-esque “Shining city upon a hill” rhetoric that the world at large hasn’t believed for a decade. Alliances and ideological leadership could have been a path America took in 2021, but not Cold War style bloc building, massive global rearmament, economic coercion, and downright delusional security policy.

None of this is to say that China is ready or willing to replace the United States as a global hegemon. China has its own real domestic economic concerns driven by an incredible emphasis on production and far less attention to the livelihoods of the working classes. Xi’s recent tours may amount to less than was promised, but the the point is that something was promised and someone was there to listen. Even this is more than the United States can muster at this point.

Civilizations can survive incompetence; they cannot survive a manufactured reality based on lies the rulers tell themselves and believe. This isn’t only true of the MAGA elite. The Democratic establishment suffers from its own backward looking fantasy of U.S. power – dreams of the good old days of humanitarian intervention and wars on terror adjusted to a smaller bloc scale as reality forces itself in at the edges.

Neither side is currently able to produce realistic suggestions for how to live in the world as it exists. An actual answer to China’s rise would require new social safety nets in America, infrastructural investment, long term industrial policy initiatives, and a willingness to take a deep inward look at the contradictions of American society. Maybe its just easier to pretend.

Stop it.