How Capable Are the U.S. and Japan of Intervening in a Taiwan Conflict?

Cultural Revolution Echoes Heard in America w/ David M. Lampton

- Interviews

Juan Zhang

Juan Zhang  Miranda Wilson

Miranda Wilson  Yawei Liu

Yawei Liu- 03/29/2025

- 0

American experts on China may not have anticipated that their knowledge of China would one day be used to explain current U.S. politics—but that is precisely what several China experts in the United States are now doing. Among them is David M. Lampton, widely recognized as one of the most prominent China experts. Recently, he has given interviews sharing his insights on China’s Cultural Revolution in the hope that the United States can avoid repeating similar mistakes. This interview was conducted against that backdrop.

In our latest interview with David Lampton, we sought his opinions on the most discussed developments relating to U.S.-China relations. Professor Lampton answered only three questions, but each response was a thoughtful and incisive mini-essay. The three topics he addressed include reflections on China’s history of the Cultural Revolution to present-day U.S. politics, the key arguments of his new book Living U.S.-China Relations: From Cold War to Cold War, and two recent initiatives by the U.S. Congress targeting Chinese students in America.

David M. Lampton is Hyman Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, Senior Research Fellow at the SAIS Foreign Policy Institute, and author of LIVING US-CHINA RELATIONS: FROM COLD WAR TO COLD WAR (2024).

U.S.-China Perception Monitor (PM): Some observers have drawn parallels between the current political climate in the U.S. under President Trump’s era and aspects of China’s Cultural Revolution. Do you see any valid comparisons? If so, what are the key similarities and differences?

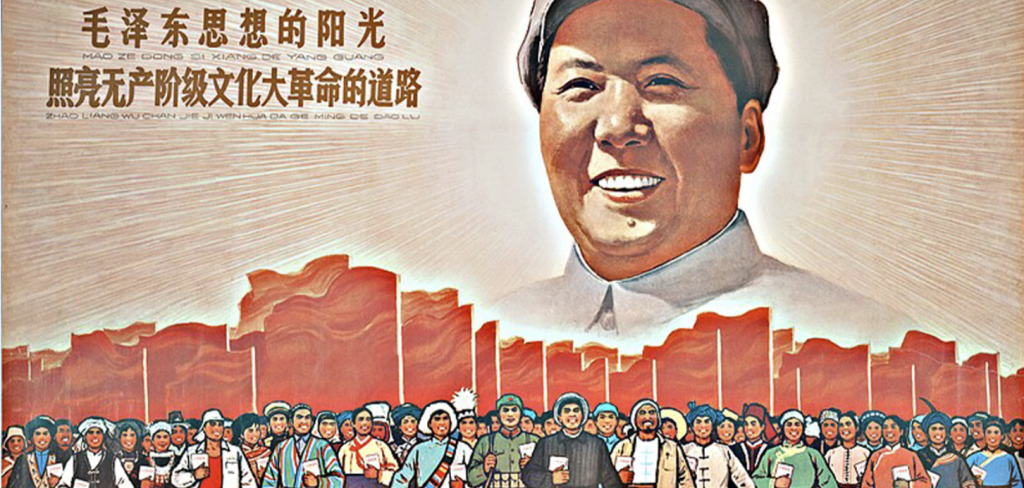

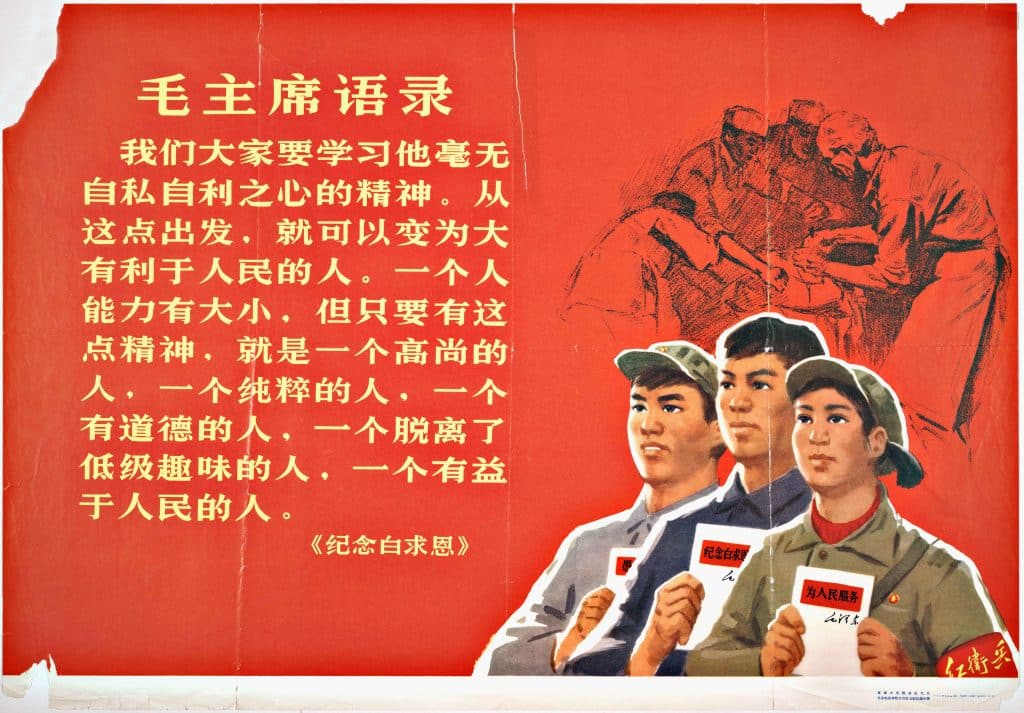

David M. Lampton (DML): Not quite sixty years ago, in August 1966, Chairman Mao, then seventy-three, unleashed his domestic cultural and political wars, becoming a decade-long movement ironically called the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. It set back China’s modernization, harmed millions, damaged China’s relations with much of the world, and took Deng Xiaoping the rest of his life to guide the country onto a much more productive path. I was in China as the Cultural Revolution era wound down in October 1976; the streets of the country’s largest cities were in a jubilation.

Now, almost six decades later, in America, I hear eerie Cultural Revolution echoes in Donald Trump’s rapid attempt to consolidate power and radically alter fundamental elements of the preexistent American institutional system and its long-standing norms and values as they apply to its actions at home and abroad. The similarities of the two eras are evident with respect to motivations and instruments. If carried to their logical extremes, these developments in America could impose enormous costs on the United States, indeed the world.

Like Mao, Donald Trump is motivated by his resentments of what he calls “the deep state.” The defining quality of bureaucracy is standardized procedures, the influence of technocrats, measured policy-making and implementation, and critical, not slavish, responsiveness to a single leader’s will. In Trump’s first term, he found himself hemmed-in by bureaucrats and institutions—he vowed to root out that “deep state” on his return to power in 2025. Likewise, Mao resented Liu Shaoqi, the Chairman’s bureaucratic bête noir of the 1960s for his putting the brakes on the Chairman’s more unwise initiatives. Both Mao and Trump sought to crush bureaucracy in order to enlarge the scope for their whims.

Trump, like Mao, also has a nostalgia for extreme forms of self-reliance, a desire to break free of the constraints that the interdependencies of modern and globalized life impose. And, perhaps above all, for both Mao and Trump, there are the personal resentments of those persons who, over their long lives, had offended them—retribution and revenge were big motivations for both men. One notes in passing the bruised egos and festering resentments that Donald Trump and Mao Zedong had when it came to their fathers.

As to instruments and processes, Mao’s authoritarian playbook has many of the same chapters as Trump’s. Among those similarities are: using irregular media (big character posters in the earlier era and social media controlled by the president and his allies today) to end run the more institutionalized media and mobilize acolytes; attacking higher education and health institutions as the opening salvo; diminishing the value of expertise and attacking science; sending Party work teams to institutions to seize leadership in China in the earlier era, a move analogous to sending Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) landing teams to seize the U.S. Agency for International Development and the United States Institute of Peace today; the public denunciation (coercion) of individuals whose location is revealed so they can be intimidated by the prospect of becoming targets of popular harassment; and, the self-conscious cultivation of a cult of personality by both leaders with overtones of supernatural mission. Most fundamentally, both Mao and Trump mobilized popular resentments of the masses to attack their opponents. Intellectuals and professionals were terrorized and their work impeached as the product of a snobbish, self-interested elite holding common people in contempt—“deplorables.” “Kill the chicken to scare the monkey.”

Among the lessons? Autocracy, coercion, cult of personality, and absence of due process are dangerous things. They can take root in social and political systems that otherwise are very different from one another.

Of course, an even-handed assessment would also acknowledge that there are differences between the China existing a half-century ago and the America of today, among which I would include deeply-rooted legal and judicial structures and a balance of power system in the United States. Though currently under attack, this bulwark of law, norms, and institutions has considerable resiliency. Moreover, Americans have important “habits of the heart”—a desire for freedom, deep individualism, and an underlying sense of fair play. Nonetheless, my country now finds itself embroiled in deep societal struggle.

PM: Your new book Living U.S.-China Relations challenges the narrative that U.S. elites naively traded away American interests in their engagement with China. What do you think is the most misunderstood aspect of this critique and how does your book provide a more nuanced perspective?

DML: This book is what I hope can fairly be described as an historically grounded, analytic, and personal look at my about sixty years of living the U.S.-China relationship. My career has given me the opportunity to see the U.S.-China relationship from the global, state, local, individual, and multilateral levels. I hope it humanizes the relationship between our two countries and peoples, something sorely lacking at the moment.

The U.S.-China relationship was given a kick start in the 1970s by Nixon-Mao and Carter-Deng, soon becoming an ever-enlarging snowball going down the mountain of our two societies, a snowball picking up supportive constituencies at all levels as it tumbled downhill. This snowball gained size and speed because groups in both our countries had important common interests—there were powerful coalitions in each of our societies supporting productive bilateral ties and we increasingly cooperated.

However, as the snowball of engagement gained mass over about four decades, it also inflicted harm on some constituencies in both countries. In turn, these self-perceived losers pushed for tougher policies in both societies aimed at the other. In this sense, engagement was not a plan, nor a strategy—rather, it was an inter-societal happening, a reflection of ever-shifting constituencies and power balances.

Now, we must find ways to increase the benefits and reduce the harms of our bilateral interaction for constituencies in both of our societies to create the necessary environment for a better future.

And second, as both nations try to address prior harms in U.S.-China relations, we must also recognize the enormous prior gains of engagement, gains ranging from medical and nutritional progress, to large mutual gains in per capita income, and to the absence of hot war between Beijing and Washington since the U.S. left Vietnam in the mid-1970s. If we fail to recognize engagement’s past gains, we certainly will insufficiently push for better days.

And finally, the book calls for both leaderships to candidly acknowledge the downward security spiral in which we now are locked in potentially deadly embrace. Each side has important misperceptions of the other, each is in danger of underestimating the other’s strengths, and each believes its core interests are jeopardized by the other’s actions. Call it Cold War, or not, it is dangerous and becoming more so.

PM: There is a troubling pattern emerging that targets Chinese students in American universities, including introducing a bill to ban visas for Chinese students and a House Select Committee sending letters to six universities demanding information about Chinese students. To what degree do these actions concern you?

DML: These actions concern me greatly, very greatly.

But, before outlining the dimensions of my concern, I am obliged to articulate a related, reciprocal consideration. It is fully understandable that Americans who, generally speaking, are more receptive to foreign students than anywhere else on earth, would question how open they want to be when the PRC has about 270,000 or so students at all levels of tertiary education here, while there are only about 1,000-plus American students on the mainland, in quite limited fields and localities, President Xi Jinping’s invitation for generally short-term US students to come to China notwithstanding. And moreover, while Chinese students generally have access to libraries, data sets, interviews, and work opportunities while here, there is no remotely equivalent access for US students in the PRC. We need mutual accommodation and mutual opening. Enough said on that.

Turning to the specific issues you raise, until recent years student exchange has been remarkably successful from the perspective of both nations, complaints about past and ongoing espionage and technology leakage notwithstanding. Knowledge of each other’s societies, language learning, research and discovery, all have been advanced by our students on each other’s campuses.

As for the United States, if we curtail PRC students, we will curtail the cultivation and utilization of great brains that benefit not only ourselves, but the world at large. Further, throwing up barriers against Chinese students and scholars puts us on a slippery slope of racial discrimination that periodically raises its ugly head, not only in America. The current detention and forced removal of an as yet small number of foreign students adds to the chill and reaches far beyond Chinese students.

Finally, given that education is a major export item in the U.S. economy, to discourage Chinese (or other foreign) students will compound what is a reckless Trump Administration trade policy that already has damaged our aircraft industry, soybean exports, and a growing list of other items. Market volatility grows by the day. Every Washington protectionist initiative will elicit retaliation, and not only from China. In short, actions such as those your question identifies are counter to our interests and our values.

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).

Miranda Wilson is a contributing editor for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor.

Yawei Liu is the Senior Advisor on China at The Carter Center and an adjunct professor of political science at Emory University.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.

Authors

-

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).

-

-

Dr. Yawei Liu serves as a senior advisor to the Carter Center’s China Focus program. He is the founding editor-in-chief of U.S.–China Perception Monitor and its Chinese-language website, 中美印象.