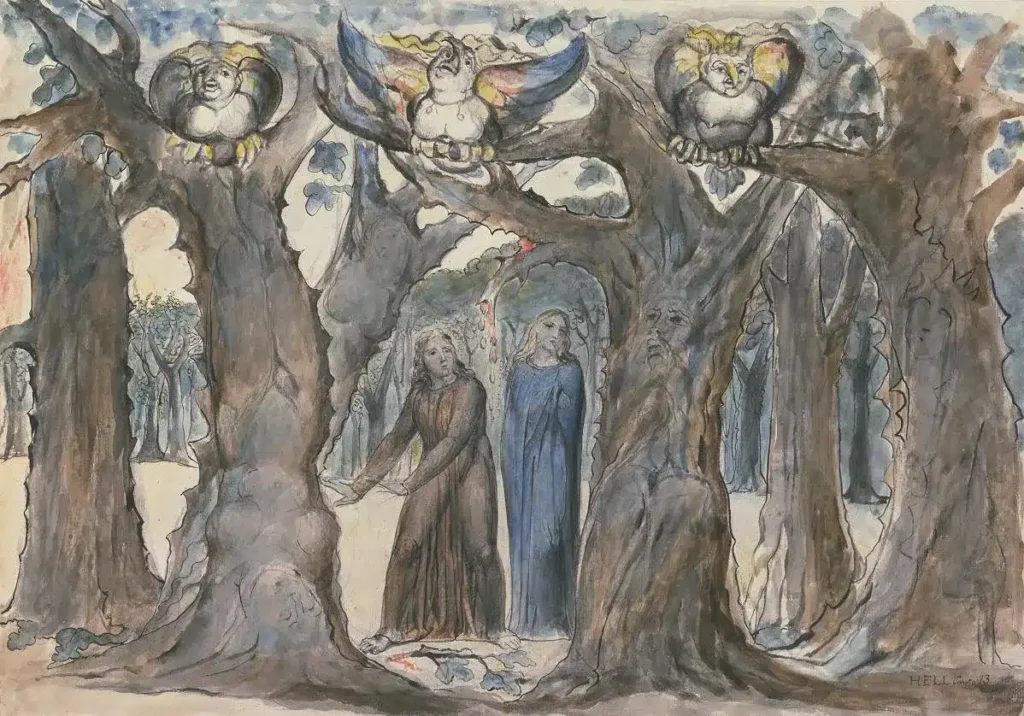

The Wood of the Self-Murderers: The Harpies and the Suicides. William Blake. c. 1824-1827.

Edward Alden is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who specializes in U.S. economic competitiveness, trade, and immigration policy. He has authored multiple books, including his most recent When the World Closed Its Doors: The Covid-19 Tragedy and the Future of Borders and Failure to Adjust: How Americans Got Left Behind in the Global Economy. Alden was the Washington and Canadian bureau chief for the Financial Times and the managing editor of the newsletter Inside U.S. Trade. His writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, Fortune, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Toronto Globe and Mail, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post.

Henry O’Connor: What do you think Trump is trying to accomplish with his trade policy? Why does he seem to be targeting both allies and adversaries, even threatening higher tariffs on Canada and Mexico than China?

Edward Alden: Trump cares deeply, and has for a very long time, about our trade deficits with other countries and sees tariffs as an all-purpose weapon that he is determined to use broadly to resolve that. If you look at Trump’s first term, he started with tariffing steel and aluminum, which mostly affected Canada, Mexico, Europe, and Japan, not China. The trade actions against China only came later in his administration.

There is also increasingly a security dimension to his use of tariffs. He campaigned very heavily on border control and has now tried to make his tariffs a weapon in that fight. While this was unexpected, we saw an inkling of this towards the end of his first term and in the later parts of his 2024 campaign. While I don’t think China has necessarily fallen down the list of concerns, his use of tariffs has expanded, which is definitely a novel development in his tariff policy.

HO: With the use of trade threats, it seems Trump has already won major optical victories with Canada, Mexico, and, particularly, El Salvador. Do you think this will encourage Trump to sustain an aggressive tariff policy for the rest of his administration?

EA: I think the unfortunate thing about this is that, and I hate to criticize reporters, the media has covered this terribly and irresponsibly. Part of the problem is that this is being covered by economic reporters, which seems reasonable, but they know nothing about border issues, immigration issues, and certainly nothing about drug control issues. Trump got nothing from these agreements that the Canadian and Mexican governments hadn’t already been doing in a significant way. The Canadian measure is only a billion dollars and a few more boots on the ground. It will make no difference in terms of the movement of drugs across that border. The Mexican government is doing things that it was already doing under the Biden administration’s cooperative negotiations. In effect, Trump’s policy is to leave the United States no better off in terms of border and drug control at the cost of enormous ill will in both countries.

HO: In 2018, during the opening shots of the last trade war, Gao Feng, China’s Ministry of Commerce Spokesperson, said, “The United States is firing at the whole world. It is also firing at itself.” How do you interpret this remark and what does it mean today?

EA: I think it is dramatically truer today, and I think the effects are going to be far more enduring than they were after the first term. Initially, it was correct, the U.S. fired at many of its allies with the steel and aluminum tariffs, but it then negotiated agreements with all of them and reworked NAFTA into the USMCA. The tariffs were the opening salvo to negotiated resolutions.

For the last few years of the administration, China was the focus, but even then, in most cases the tariffs were removed after a deal was negotiated. This time around, I think that remark is going to hold much more strongly. The initial actions against Canada were shocking and a massive violation of the trade deal that Trump himself negotiated and claimed was “the greatest trade deal ever.” To right out of the box tear up his own agreement and threaten tariffs is about as radical a move as the president could make. He seems to be saying that we have no friends on trade anymore, everyone is our potential adversary, and if we can go after Canada and Mexico, nowhere else in the world is safe.

There really isn’t a country that is safe from the tariff threats of the United States, and I think this will rebound on the United States in two primary ways.

To the extent that the tariffs are implemented, and they already have in a small way, they are going to raise the costs for consumers in the United States. There will be retaliation that will hurt the farmers and manufacturers in the United States. But the bigger damage is going to be our reputation. We are the country that led the creation of the modern rules-based global trading system, and we’ve reached a point where we are not just violating it around the edges, but we are violating it in very fundamental ways.

We have declared to the world that we are not bound by the rules that we took nearly a century to painfully negotiate with countries across the world. There will be enormous reputational damage to the United States. The whole values argument that the United States has made about why organized rules-based trade is better has just gone completely out the window. So, is this a gift to the Chinese? Absolutely.

Do you see the United States starting to engage in ‘big country’ diplomacy or more coercive economic actions in the future?

That’s a polite term for it, so let’s just call it what it is: economic bullying. I know that countries use economic weapons for all sorts of ends, and it may be quite appropriate to use these weapons to deal with nations that are hostile to the United States, but to use these weapons against your friends just undermines your own alliances. The biggest advantage that the United States has in the great power competition is that we have a lot more friends than they do. Our alliances are bigger, wealthier, and much more enduring. What Trump is doing is weakening the greatest asset we have in this new age of competition. So, if it’s ‘Big Country Diplomacy’ as you put it, it’s extraordinarily inept. Big country diplomacy doesn’t just mean throwing your weight around in ill-considered ways, it’s making sure your assets are stronger than the assets of your rivals. We on the other hand are busy weakening our assets.

HO: Could you see political or economic decoupling from the United States in the future?

EA: I think decoupling is too strong a term. Certainly, with Canada and Mexico, there are enormous limitations on how much they can decouple. 80% of their exports go to the United States after all. I think that many countries who were previously reluctant to engage more deeply with China will begin to ask themselves what choices they have now. Trade with China is a losing proposition; we can’t compete with their heavily subsidized industry. The Americans are putting tariffs on us, what are we going to do? They will split the difference the best they can, and there will be efforts to cozy up to the Europeans. The Canadians are going to try that, the Mexicans just signed a free trade agreement. Everyone will be looking for alternatives. While there isn’t a way for most countries to decouple from the U.S. economy, alternatives to the United States will become far more attractive than they once were.

HO: Do you think that Europe could stand to gain from this new emerging dynamic?

EA: It’s certainly possible, they’ve already gained economically by cutting new deals with China, something they’ve been traditionally reluctant to do. The Europeans have tried to stand firm with the United States in reducing their ties to China, but if you look at, for example, the Germans who sell so much to China, they’ve taken a hit losing market opportunities over there. I think you’re going to see the Europeans say, “Well look, dealing with the Americans, dealing with the Chinese, 6 on one hand, half a dozen on the other.” They’ll try to find new places to cooperate with China to their own economic advantage, but it’s hard for me to see this being a net positive for Europe. There are no winners in trade wars.

HO: How will an American pullback affect the wealth and economic strength of our closest allies?

EA: Everyone will end up worse as a result of what Trump is doing simply because basic comparative advantage economics, while more complicated today, still hold in large measure. The larger the market, the more room there is for specialization and efficiency, which raises global wealth. Now, we are seeing a return of tribalist economics which forces the Canadians to talk about self-sufficiency and interprovincial trade. The Canadians will be much poorer as a result, but they won’t have a choice in the matter. It’s a net loss for everyone, but the alternative is to be at the mercy of a bullying and unpredictable United States and a bullying but more predictable China.

HO: After the Biden administration chose to sustain many of Trump’s tariffs from his first term, do you think this represents the start of a long-term retreat from international trade and diplomacy? What role, if any, do you see for China to fill that gap?

EA: I would not describe Biden as having withdrawn from trade and diplomacy. While Biden did not sign any new trade deals, which I think was a mistake, he engaged in broader initiatives to ‘friend-shore’ supply chains. For example, relocating business away from China to friendlier more reliable partners. Trump on the other hand, has thrown the friend-shoring piece out the window. He’s not happy if it moves to Vietnam, Mexico, or Canada, he wants it all to move to the United States.

This essentially sets up a zero-sum relationship with our allies. The lack of choice may require some countries to try and work with China, but a lot of these economies are going to be starting over again. Canada’s entire economy has more or less been built around full access to the U.S. market and the same is true for Mexico since NAFTA. These countries don’t have a plan B. They didn’t ever think this would actually happen.

HO: Could Trump’s tariffs just send supply-chains out of both China and the United States? Would tariffs hurt China’s competitive advantage, but not necessarily make us a more attractive option?

EA: That was the experience around the middle of the first Trump administration and continuing into the Biden administration. A small amount came to the United States, but most of it went from China to other lower-cost markets. Trump’s hope is that, and let’s not sane wash his policy, companies will believe they can’t access the U.S. market from anywhere other than the United States. Some of that may happen, but more likely is that companies will sit on their cash and wait for the dust to settle before investing. If America truly turns inward, they might invest some domestic production in the United States, but the rest will go elsewhere for global production.

HO: What is de-dollarization and do you expect a renewed push in the coming years?

EA: De-dollarization is when countries find ways to make their transactions in order to limit U.S. leverage. While we’ve seen a bit of this, it is certainly not significant. The Trump claim that he’s going to tariff BRICS if they move away from the use of the U.S. dollar is just bizarre. In fact, if he wants manufacturing to come to the United States and put us in a more competitive trade position, de-dollarization would be a perfectly good thing. One of the things that keeps the value of the dollar so high is that it’s used all over the world for a whole range of transactions. To threaten BRICs with tariffs if they reduce their use of the U.S. dollar is incomprehensible.

HO: Assuming Trump’s goal is to make us a manufacturing powerhouse, are tariffs an effective measure to close the trade gap?

EA: Firstly, no, tariffs are not an effective way to close the trade gap. There are fundamental reasons for the trade gap that have more to do with savings, consumer demand, and mercantile practices by China. Secondly, to rebalance American trade, tariffs would have to be set at such a level that would put the United States and global economies into a deep recession. That said, there are circumstances where tariffs are an appropriate measure. China for one egregiously uses all sorts of trade-questionable techniques to hold down the value of their exports, including government subsidies and value manipulation. What’s extremely unhelpful is that he is not using tariffs in that way but rather jumping between targeted tariffs that have nothing to do with trade deficits and universal tariffs which would be harmful across the board. I’m not opposed to targeted tariffs; it’s the ill-considered and untargeted use that I disagree with.

HO: Why don’t we use subsidies and other measures to bolster our export markets?

EA: We do now, but we didn’t for a very long time. One goal of the WTO system was to maximize efficiency on a global scale, which is something you don’t want distorted by government subsidies. If governments are showering companies with money, that would produce a poor allocation of labor, right? Companies would move where they otherwise wouldn’t, and other governments would be forced to respond with their own cash to not lose investment. It was always a good idea in theory, not that it worked all that well in practice.

The Chinese probably exploited it more than anyone, but they were far from alone in this. In fact, a decision from the WTO appellate body that really broke the back of the WTO ruled the way China was subsidizing industry was not in contravention of WTO rules. It essentially green-lighted all these practices by China. What the United States did during the Biden administration was say if we can’t beat ‘em, we’re gonna join ‘em.

The Inflation Reduction Act and the Chips and Science Act were essentially massive subsidy programs for American industry to the point that it pissed off the Europeans. So now, on the cusp of a global trade war, we have been in a global subsidy war for five or six years already by this point.

HO: Do you think the United States is well positioned to win the subsidy war? Do you think China can double down on their existing subsidy regime?

EA: China already has and you don’t win in that; look at their electric vehicles. It becomes this zero-sum game in which you in effect steal investment from other places through subsidies, which just gets expensive for taxpayers. Agriculture industry, for example, has always been subsidized here in the United States, and we’re going to pay even more there because of it. Farmers will suffer from retaliation, which we already saw in Trump’s first term. A colleague of mine, Ben Steel at the Council on Foreign Relations, has a piece showing how all the revenue collected on the China tariffs was used to subsidize farmers during Trump’s first term. This is a lose-lose that maybe we ‘win’ because we’re relatively worse off, but absolutely everyone will be worse off for it.

HO: Does China have an effective response to the tariffs? Will their WTO lawsuit have meaningful consequences?

EA: Even if China wins in the WTO, the United States has shown it is no longer willing to abide by the rules of the game. They have a judicious response to this, because well, they don’t have any decent tit-for-tat tariff response. China sells so much more to the United States than it buys. They’re talking about export restraints on critical minerals that could have a short-term impact, but the United States has been busy spending the last 5 years trying to find new sources for that anyway. We’re not nearly as vulnerable as we were five or six years ago. China’s long-term response will be to try and find new markets as their exports have remained strong despite the tariffs, but I don’t think China has an economic arsenal that could force a U.S. retreat if the United States is determined to go through with a trade war. The same is true for Canada and Mexico. The United States just has more weapons in this fight.

HO: To what extent is this all just economic shock doctrine?

EA: The shock doctrine we seem to be seeing out of this administration is its dismantling of government institutions like USAID, but it’s far from clear what the aim is. At least shock doctrine theory, whether you thought it was good or not, had some idea about what was on the other side of it: a better functioning market economy. I don’t think shock doctrine is appropriate for their government efforts; their idea is to have a leaner government, which could be a good thing, but will not be good for people around the world who rely on subsidized HIV drugs and who are going to die as a result. I just don’t think it’s an appropriate term for what they are trying to do.

Henry O’Connor is an intern at The Carter Center’s China Focus initiative.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.