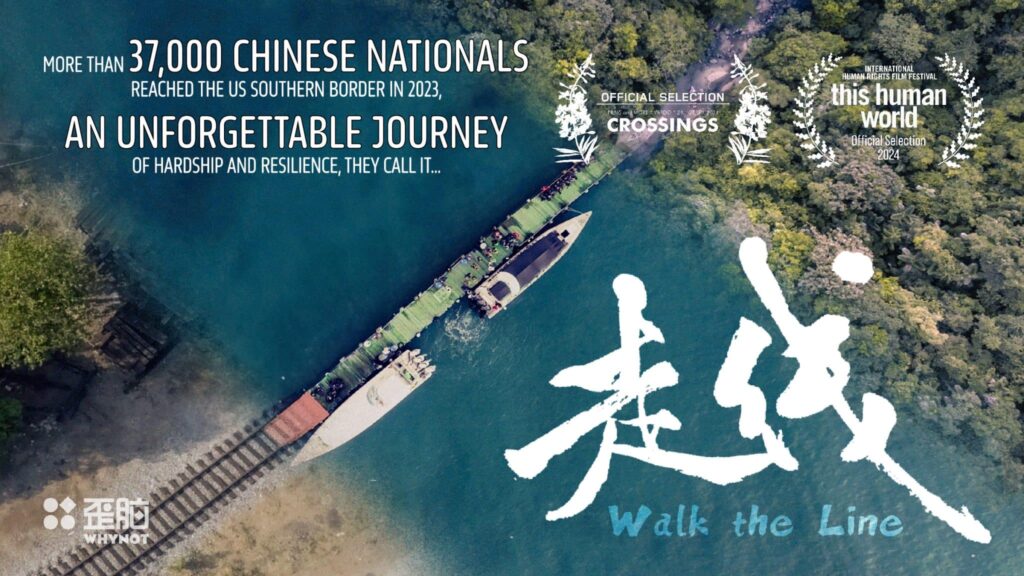

In September 2024, The Carter Center hosted a closed screening event for WHYNOT‘s first feature-length documentary film, “Walk the Line.” Co-director Vivian Lee joined us for a panel discussion with Georgia Tech’s Lu Liu to answer questions about the film and the 2023 surge in Chinese migrants at the U.S. southern border. Last month, The Monitor had a chance to talk with Vivian Lee again about the documentary and Chinese migration patterns.

“Walk the Line” tells the story of several Chinese nationals who embark on a treacherous journey across the Darién Gap in an effort to reach the United States. While a lot has changed since the documentary’s team followed the migrants on the ground (Ecuador is no longer allowing visa-free entry for Chinese nationals), the themes of the film remain relevant amid an evolving U.S. immigration policy. Recently increased restrictions include the indefinite suspension of asylum, drastically changing migration flows into the U.S.

Vivian Lee shares how the film sheds new light on the situation in China, exposing the hardships that pushed these migrants out and what they came to find. Fundamentally, it is a documentary about the risks that came with their quest for freedom.

Vivian Lee (歪脑|WHYNOT) is a director, producer, and writer. Born in Beijing and based in Washington DC, Lee is a multidisciplinary storyteller who has worked creatively across a broad range of platforms to share real human experiences. She is the Deputy Director at 歪脑|WHYNOT, where she continues to bring attention to overlooked social injustices and underrepresented communities. She has produced thought-provoking works such as the documentary short The Young People Who “Ran” out of China, Are Their Dreams Coming True?, which won the ONA 2023 Digital Video Storytelling award. “Walk the Line” is Vivian’s documentary feature debut.

歪脑|WHYNOT is a Mandarin digital news magazine affiliated with Radio Free Asia, providing probing journalistic content that engages young Chinese-speaking audiences both inside and outside China.

Miranda Wilson: What was the motivation behind creating the documentary “Walk the Line”?

Vivian Lee: Reporting China from the outside is always very challenging. We want to present on the front line with Chinese issues. For “Walk the Line,” the phenomenon of immigration is very critical for understanding what happened inside China. The Darién Gap is not just a physical hurdle but also a symbol of the immense challenges and risks people endure in pursuit of freedom and a better life, especially for migrants from China.

This whole trend of migration out of China is very different from the conventional narratives that we have reported over the years. China is the world’s second-largest economy and is a superpower country. But its citizens are facing the difficult journey of trekking through the Darién Gap because they are looking for a better life. We wanted to understand why they chose to leave and why freedom mattered that much to them. We wanted to shed light on this lesser-known phenomenon. Also, today, immigration coverage consists of statistics and political rhetoric — we wanted to instead put a spotlight on the resilience, dreams, and struggles of these individuals who choose to embark on this journey.

MW: Could you talk a little bit about the filming process? What was it like for the crew that was with the migrants?

VL: Filming “Walk the Line” was both physically demanding and emotionally intense. Our crew had to navigate the extreme environment, from the dense jungles to unpredictable weather, sharing the same hardship faced by the migrants. The crew witnessed the migrants’ courage and vulnerability firsthand. That created this deep sense of responsibility to tell their story authentically.

On YouTube, some viewers commented that they had the same experience, and they think the film is authentic. They said it made them feel like they were walking along with the migrants.

We are very lucky that our very talented and hardworking co-director, Alicia Chen, spearheaded this project. She was the one on the frontline, along with our two cameramen and our associate producer. They are the soul of this project and without them, there would not be a film. We are so lucky that we found some migrants that were willing to speak with us. That’s also something that was challenging about the filming process because a lot of the Chinese migrants were afraid that their families in China would get harassed by the authorities. They were afraid to speak to the media. However, because Radio Free Asia and WHYNOT have been very trustworthy among the Chinese asylum seeking community, and Alicia patiently talked and listened to the interviewees, we were able to gain their trust.

MW: As your film highlights, crossing the Darién Gap is extraordinarily treacherous. For those who haven’t yet watched the film, would you mind sharing how Chinese immigrants attempt to enter the United States using the Darién Gap and some of the dangers they encounter?

VL: A lot has changed now, but at the time of our production, Chinese migrants typically began their journey in Turkey, traveling from there to Quito, Ecuador where they were able to enter with a more relaxed visa requirement, which has changed since July 2024. Since then, Ecuador is no longer permitting visa-free entry for Chinese nationals.

But back then these migrants could enter Quito and then traverse the route up to the Darién Gap, which is a roughly 60-mile stretch of roadless land between Colombia and Panama. It is a lawless jungle with natural and manmade threats.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people from all over the world cross the Darién gap heading to the United States. Migrants face torrential rains, wildlife, and lack of food and clean water. Moreover, they risk encounters with cartels or criminal groups, combined with physical exhaustion and emotional strain the whole journey.

MW: What do we learn about Chinese immigration to the United States through the format of a documentary? How does film help humanize the immigrant experience?

VL: Since WHYNOT and RFA is a news agency, we are very familiar with up-to-date reporting, but this is our first feature-length documentary. It was quite a different mindset for us to not think about needing to break the news; we were there to report part of history. There are already a lot of news clips and TV docuseries about this constantly evolving issue. We were hoping to be a time capsule of this particular period. Years later, we are hoping that when people want to learn more about this part of history, our film is the go-to footage for focusing on these Chinese migrants.

Through documentary, we hope that the audience can gain an intimate perspective on the complexities of Chinese asylum seekers. The push factor, like the harsh COVID-19 policy in China, the economic downturn afterward, and political and human rights repression — and the pull factor, the hopes and dreams that they hold, and the longing for new opportunities. Our film uniquely captures these raw emotions and the voices and faces of these individuals in a way that statistics and written articles might not be able to. I am very touched by the thousands of YouTube comments saying that the documentary has moved them to tears. I think that’s the magic of the film.

MW: As you mentioned, the migrants that your film follows choose to leave China for a variety of reasons: to escape LGBTQ+ discrimination, unemployment, and the harsh Zero-COVID policies. Even though their motivations are different, are there important characteristics that these individuals’ stories have in common?

VL: Despite their diverse motivations, the migrants share common traits of resourcefulness and resilience. They also share a sense of hope and a willingness to take extraordinary risks. Their journey underscores a shared belief in the possibility of a better future, even when the odds are stacked against them.

Additionally, their stories highlight a universal longing for dignity, safety, and self-expression, values that transcend culture and national boundaries. During one of our screenings in Vienna, someone asked, “These Chinese migrants seem like they have a lot of resources compared to people from other parts of the world, so why are you focusing on them?” I thought: Suffering has no hierarchy. Suffering is universal. When the Chinese migrants have their kids on a “death boat” in the middle of the Caribbean Sea and they’re screaming and crying and everyone thinks they might die — I don’t think about who is suffering more or who has more resources.

MW: Only one female migrant agreed to be on camera. How was her experience different from her male counterparts?

VL: Like I said before, getting interviewees to speak on camera was one of the biggest challenges for our film. Many were afraid that their family back home would be harassed. We totally understood and respected this fear. This fear was especially salient for women interviewees. Our co-director Alicia Chen, spoke with many women — like single mothers with children on the road. They were very open about their vulnerability and the challenges they encountered, but they were not willing to talk about them on camera.

Our core creative team is dominated by women. Women always have a strong voice at WHYNOT. We knew we wanted to highlight the female perspective and experience, the unique gender-specific challenges such as heightened vulnerability to exploitation and harassment during the journey. Cindy’s courage in sharing her story underscores the additional resilience required by women on this journey. Also, the mother who shared her story about being robbed and assaulted. It adds depth to the documentary revealing how gender dynamics shaped the migrants’ experiences.

MW: Similarly, the LGBTQ+ couple chose not to reveal their faces until they reached safety in the U.S. How did your film crew navigate ethical questions of keeping participants safe while also wanting to share their stories?

VL: Building trust and fostering a relationship with subjects in this high-stakes situation required a thoughtful and empathetic approach. Our brilliant co-director and producer, Alicia, played a pivotal role in this process. Over the course of the project, she connected with more than 30 individuals and spent a significant time listening to their stories without judgment to ensure they felt heard and respected. Ultimately, only a third of them choose to participate in our film. From the beginning, Alicia was very transparent about the purpose of this documentary and her role. The credibility of our organization, Radio Free Asia, among the Chinese asylum seekers, as well as WHYNOT, which focuses on the Chinese diaspora group, were critical to laying the foundation of trust, coupled with Alicia’s background in being from Taiwan, which is a haven for Chinese civic movement and culture.

Alicia’s consistent presence walking through the Darién Gap with the migrants earned their trust and showed her commitment to these subjects, encouraging them to share their stories and open up to us. Additionally, in our post-production process, we implemented safeguards to protect our subjects’ identities. Even after filming, we maintained a relationship with the subjects to show that our connection is not only transactional but that there is ongoing support to strengthen the trust. The growth of trust is shown in our film: once we reunited with the subjects in the United States, eight months after their journey, they, especially the gay couple, were willing to reveal their faces to us.

MW: Out of curiosity, are you still in touch with any of the subjects of the film?

VL: Yes, yes. We are still in contact with most of the people. At one of the screenings in New York, the organizer wanted to have them attend the screening, but they respectfully declined the offer. I think they are focusing on their lives. But I do know that Mr. Yu is very happy with the film, which means the world to us.

MW: In 2023, more than 37,000 Chinese immigrants were detained for attempting to enter the United States illegally, more than the past 10 years combined. How do you think this issue shapes the U.S.-China relationship?

VL: As journalists, our focus is more on documenting key political and cultural moments in time. I will leave this to the policy experts.

MW: From a journalism perspective, do you have any thoughts about how Trump’s presidency might impact the immigration issue?

VL: It’s hard to say with certainty how government policy will change the migration path and the plans of Chinese nationals. Again, I will leave the speculation to the policy experts.

But since 2024, Beijing and Washington have resumed cooperation on the deportation of Chinese migrants who are in the U.S. illegally, and the latest data shows a significant decrease in the number of Chinese nationals at the southern border.

MW: At the end of the film, the individuals have very different outcomes; some are happier with their new lives in the United States than others. What do you think this says about the idea of an “American Dream”?

VL: The different outcomes reflect the complexity of the American dream. For some, it represents opportunity and fulfillment. For others, it underscores the challenge of adaptation, economic insecurity, and culture shock. The documentary suggests that the American dream is not a one-size-fits-all narrative but a deeply personal journey shaped by each individual’s circumstances and societal structures. It is different for everyone.

People mentioned that there is a comparison between the Chinese dream and the American dream. After audiences watch the film, we do not want them to feel like we’ve provided an answer, but instead, challenge them to explore whether we are asking the right questions.

Miranda Wilson is a contributing editor for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.