China Studies and the NatSec Gamble

- Analysis

Nick Zeller

Nick Zeller- 02/11/2025

- 0

Fifty years after the war, we are still organizing knowledge as if – in the case of Japan, China, and the former Soviet Union – we are confronted by an implacable enemy and thus driven by the desire to know it in order to destroy it or learn how to sleep with it.

Harry Harootunian (1)

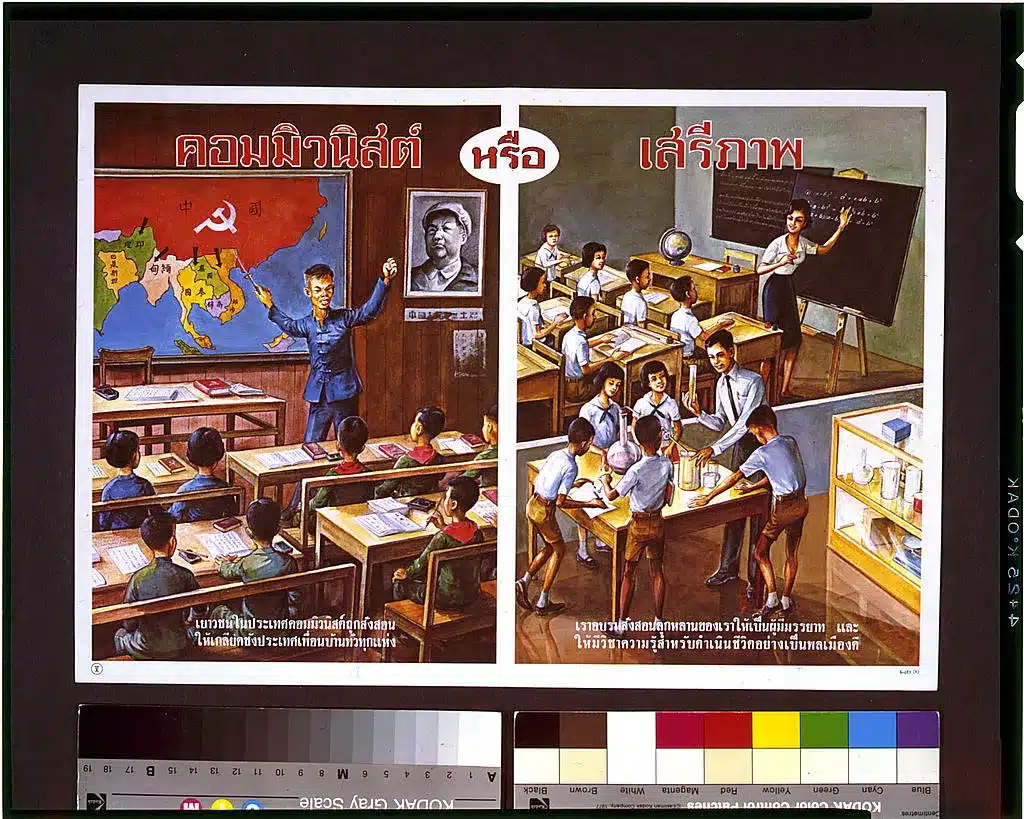

Area studies was born of the Cold War. The organization of interdisciplinary research and teaching by region and nation-state was a project of a differently guilty age when it was believed that the social sciences and humanities could churn out experts capable of producing valuable intelligence for the maintenance of empire (2). Of course, this was not a new concept. Western European powers of the 19th century developed their own specialists who developed their own theories about societies in the East under the banner of Orientalism.

In the United States, two things set area studies apart from its European forerunners. First, the study of the East, friend or enemy, took on new scientific, rational dimensions through the inclusion of political science and sociology alongside the older qualitative practices of anthropology and anything else that might fall under cultural studies. Second, the opening of government coffers for area studies after World War II coincided with an explosion in public funding for higher education in general. From 1949 to 1986, the total number of publicly funded colleges and universities in America more than doubled.

Asian studies is simply a subset of this larger trend and China studies (a euphemism for all China-focused research in the social sciences and humanities) simply a subset of that, albeit a very geopolitically important one at present. A joke I once heard from Mike Cullinane in his Introduction to Southeast Asia course illustrates the point about the origins and purpose of Asian studies. To paraphrase, Southeast Asia is a 1,700,000 square mile area with a population of 675 million people speaking hundreds of different languages, holding every major faith alongside innumerable local beliefs, and living in 11 different countries. What makes it a coherent region? The U.S. government says it is, and they approve the grants.

It would be unfair to say all China studies faculty were or are actively working in support of national security concerns in the West. The explosion of Asian studies also created many critics of U.S. empire. The most famous academic group in this vein was undoubtedly the Committee for Concerned Asian Scholars (3), whose founding members include the hall-of-famers in China studies: Elizabeth Perry, Susan Shirk, Maurice Meisner, Joseph Esherick, Paul Pickowicz, etc. When this group finally gained access to China, which they had studied from the outside for years, there were many broken hearts and a few rightward political turns, but it is still important to note that the funding source does not always dictate the ideological outcomes of research (4).

In the main, however, Harry Harootunian’s description of the project of Asian or area studies during the Cold War is accurate:

Once the organization of area knowledge was fixed, soon after World War II, all that remained were periodic adjustments to the changing political realities throughout the world and discussion of how the structures it sanctioned [area studies] could be sustained. This anxiety was expressed in the obsessive search for money here and abroad, which has become the principal preoccupation of area studies in the established universities and colleges of the United States and probably the United Kingdom (5).

The political realities of the world have changed greatly since the Cold War. For China studies, these changes have mostly manifested as declining support from the U.S. government (with an important window of incredible exception). In response to this decline, some academics seem determined to return to the Cold War Asian studies-national security alignment, or at least unable to imagine anything different. If China is the greatest threat to U.S. national security, the China studies scholar asks, why aren’t we funding more research on China? There are two problems with this. The first is that most China studies scholars in America are not so hawkish on China as they are desperate for funding. Given the overall weakness of the Cold War generation of researchers to change U.S. foreign policy (yes, people like Susan Shirk eventually held policy positions, but rapprochement was about U.S. failures in Vietnam and the Sino-Soviet split) (6), it’s not clear a return to the Cold War model would result in more influence today. Second, the expectation for robust funding of China research flagrantly avoids the larger problem. American higher education is in crisis on all fronts. China scholars’ crabs-in-a-bucket struggle for grants is not a unique product of U.S.-China rivalry; it’s a return to what the rest of academia was already experiencing.

The Crisis in China Studies

Let’s start with what has changed in China studies. The hardships of China studies scholars in America and the West have been getting new attention. Without a doubt, the most important obstacle is China’s own censorship of its archives and restrictions on researchers. Yet, apart from this, America seems suddenly disinterested in its great rival. (Academically, at least. Xiaohongshu and the TikTok refugees are another issue.) In a forthcoming working paper, Princeton professor Rory Truex and co-author Alexis Dale-Huang find that National Science Foundation (NSF) grants for China research at American universities reached their height in 2008 and have plummeted by more than 50% during the Xi Jinping era. NSF grants to study China in the social sciences have fallen by more than two-thirds since 2012.

Funding for (typically) undergraduate study of China has also been dynamited in the last decade. In 2018, Congress restricted funding to universities with Confucius Institutes, admittedly spotty language teaching centers funded by the Chinese government, over influence concerns. As a result, over 100 Chinese language centers across the United States closed. What influence Confucius Institutes exerted over places like the University of Wisconsin – Platteville is not entirely clear, but it is even less clear how smaller universities are supposed to make up for the loss in language instruction.

The U.S. State Department offers intensive, in-country language instruction to American college students through the Critical Language Scholarship Program, but that program has not offered in-person courses in China since 2022. Accepted participants are directed instead to Taiwan (a great option, but not the mainland) or online courses operated out of China and Singapore. Similar programs like the National Security Education Program’s Boren Awards (a Defense Department program) have also closed their China options. The former program sent me on my first trip to China in 2015, where I spent a summer in Dalian. The latter paid for my dissertation research. When I say this is a loss, I know of what I speak, and none of this is to mention the very high-profile loss of Fulbright exchanges between the United States and China in 2020.

Combined with the Justice Department’s failed and shuttered “China Initiative,” launched in 2018 to rout out mostly non-existent espionage by Chinese faculty and students, and the slow creep of broader anti-Chinese discrimination onto university campuses, it is easy to explain the collapse of U.S. funding to study China as a symptom of their abysmal bilateral relations. It is so much worse than that.

If Trump can deliver on his promise to abolish the Department of Education, he will destroy the main source of funding for Title VI National Resource Centers. These are area-focused centers at universities that fund language learning and research. In 2022, only 15% of the $72 million marked for Title VI centers went to East Asia programs. With these centers already on tight budgets, no Department of Education means no Title VI means no Center for Chinese Studies.

But abolishing (or more likely defunding and AI empowering) the Department of Education has implications for higher education well beyond China studies, and that is something not often mentioned in the NatSec-tinted discussions of this issue. Yes, funding to study China is drying up at a time when Americans’ Cold War experience of area studies dictates it should be increasing. However, there is a wider context here.

The Crisis in the Studies of Everything

American universities are currently in a homegrown crisis, one that is exacerbated by but pre-dates the abysmal turn in U.S.-China relations. Let’s start with employment.

According to the American Association of University Professors, the tenure system in American universities “has all but collapsed.” Tenure basically means it is very difficult for you to be fired. It’s job security for academics. It is supposed to provide workplace autonomy and foster intellectual creativity. It has always been an elitist system. Janitorial, administrative, and maintenance staff have never been offered similar guarantees. Nonetheless, for those who have it, it offers a chance for innovative research – research on China, yes, but on everything and everywhere else as well.

In 1987, 53% of American university faculty were tenured or had a job that would lead to it. By 2024, that figure fell to 30%. Now, half of the American academic workforce is part-time employees, most of whom make less than $50,000 per year with no job security and few benefits. Most of them are skilled teachers stuck in dead-end jobs partly out of false hope that the whole system will turn around and partly because a Ph.D. is a millstone around your neck in nearly all job markets.

Meanwhile, over the last 40 years, administrative positions in universities have grown by 164% and professional positions by 452%. During the same period, the university student population only grew by 78%. Your average undergraduate student borrows over $30,000 during their degrees to pay tuition costs, which have grown almost 200% since the 1960s.

University coffers have skyrocketed, but the money isn’t for teaching or research. The problem of where the money is going is beyond my scope here, but it’s worth noting that tuition revenue is about to take a huge hit as the population of college-age Americans rapidly declines. Many universities already depend on Chinese students (second to Indian students for the largest group of international students in America) to make up for sagging enrollment figures. While some think tankers argue to reduce the number of Chinese international students in certain majors, it isn’t clear what American universities will do to make up for lost revenue when (not if) we fall off the enrollment cliff. The answer will undoubtedly involve administrative layoffs and larger online courses taught by whole battalions of temps. The total number of degree-granting colleges and universities of any kind in America has been declining since 2013. Under current conditions in the United States, closure can only accelerate.

It’s notable that many of the printed complaints about the loss of research funding to study China come from Ivy League and blue-chip state school faculty. Where else are there faculty with the job security and economic comfort to expect to live out the good ole days of China research? These folks aren’t wrong. I adamantly agree that the decline of China research in America is a problem. The question is simply whether the answer is to demand a national security-backed exemption from the current dreadful trends in American higher education and return to the Cold War model or build something else.

No Cold War Redux

The framing of the U.S.-China rivalry as a second or new Cold War has been around for over a decade. Although some have suggested more accurate phrases like “inter-imperial rivalry,” the naming of the situation we are now in is settled for the time being (7). It is unfortunate because there are several problems with the Cold War analogy. For one, there is nothing now similar to the radically ideologically opposed visions of the future that animated the 2.5 (United States vs. Soviet Union vs. sometimes China) sides of the original conflict. It’s also questionable to what degree people invoking this term remember how hot the wars of that era were. During the first Cold War, the United States attempted to overthrow the government of a foreign country 72 times. This is not to say that China didn’t have a few irons in that fire as well. Are we headed back to that?

More important for the point here, however, is that there is none of the social investment in the United States that marked so much of the old Cold War. At the end of the American century, the United States is led by an administration that, despite the neocon resumes of many folks close to the top, answers to a president who views alliances as potential protection rackets and is happy to close the grant funding valve on any research suddenly and without warning. There aren’t just political and ethical reasons China studies scholars shouldn’t gamble on national security arguments to keep their work funded. Even if they were successful, and there are still massive defense grants out there, it isn’t a sustainable alternative. The impulse to destroy higher education in general in the United States is simply too great. China studies scholars either fight that impulse head-on at home or give fuel to the fire of nationalist, militarist, and authoritarian camps on all sides hoping for fleeting warmth.

(4) Fabio Lanza, The End of Concern: Maoist China, Activism, and Asian Studies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

(5) Harootunian, History’s Disquiet, 27.

(6) Shirk’s time in the State Department was 20 years after rapprochement. My point here is that left-leaning China studies scholars didn’t have an impact during the Cold War.

(7) Eli Friedman et al., China in Global Capitalism: Building International Solidarity against Imperial Rivalry (Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2024).

Nick Zeller is editor of The Monitor and a senior program associate for China Focus at The Carter Center.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.