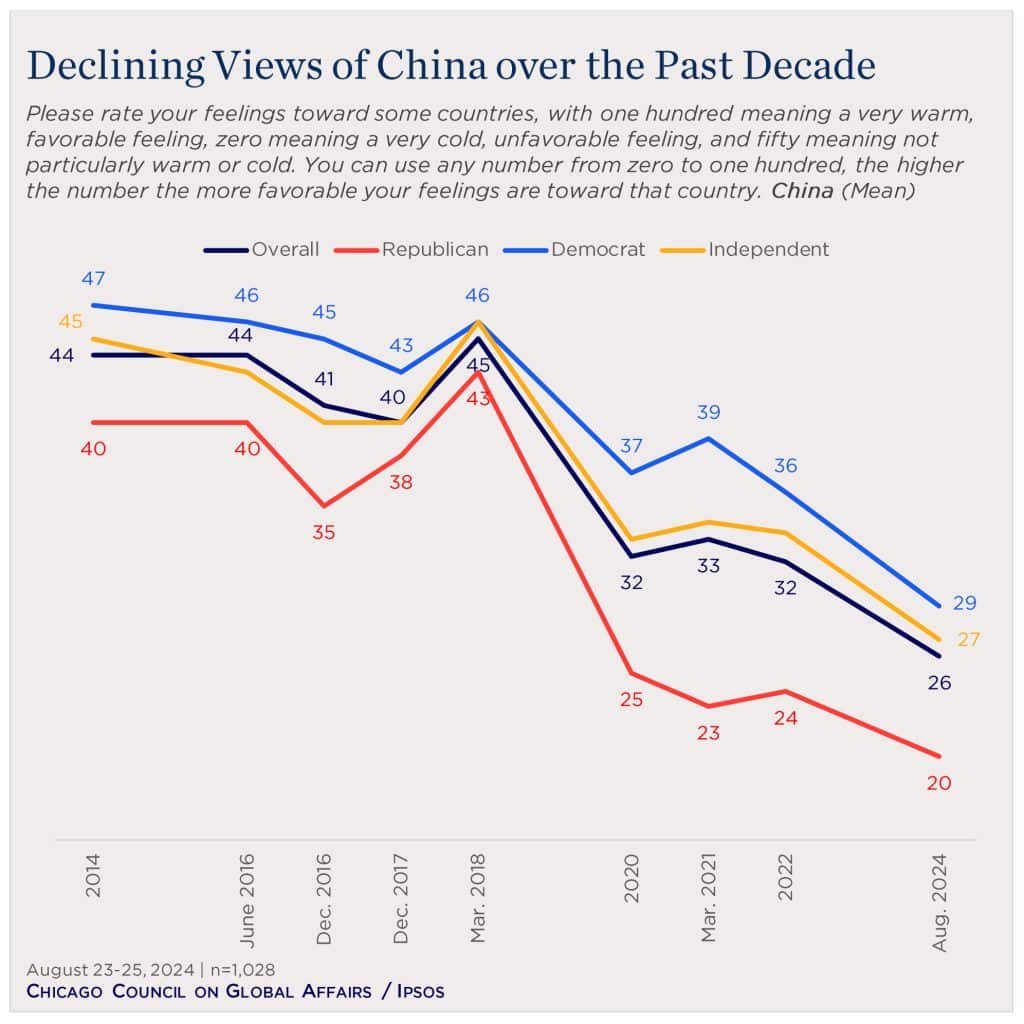

It’s no surprise that Americans view China in a grim light. In May, Pew Research Center issued a report showing, for the fifth year in a row, roughly 80% of Americans held “unfavorable opinions” on China. A recent Chicago Council on Global Affairs report asked American respondents to rate their feelings about China from 0 to 100, with higher numbers indicating more favorable feelings. In ten years of polling, Americans’ rating of China crested in 2018 at 45 and has since plummeted to 26. It’s a transition from a point of imaginable tolerance to one of looming hostility.

Across the political spectrum, Chicago Council figures indicate three-quarters of Americans see the United States and China as rivals. Fully half interpret the rise of China as a world power as a critical threat to the “vital interests of the United States.” According to a Gallup poll from last year, only 15% of Americans viewed China favorably. Broken down by political party identification, the figures for Republicans (6%) and Democrats (18%) tell roughly the same story.

From the perspective of easing bilateral tensions and avoiding outright conflict, these figures are dispiriting. As research findings, however, it feels a bit like asking if kittens are cute.

There is a causal issue in understanding political opinion polling. Do the polls reflect the efficacy of political messaging or does the political messaging reflect the broader sentiment of the people uncovered by the poll? In the case of American attitudes toward China, the lockstep positions of most people and their political elite make this a particularly difficult question to answer. The recent election of Donald Trump for a second term as president provides little clarity. During the election, an aggressive position toward China was a bipartisan issue – part of the China consensus.

At the Democratic National Convention in August, Kamala Harris promised to ensure that “America, not China, wins the competition for the 21st century.” This zero-sum framing of U.S.-China relations came immediately after she pledged America would always have “the strongest, most lethal fighting force in the world.” Even her less bellicose rhetoric around China – talk of “de-risking” – evoked nativism and American dominance. “It’s not about pulling out, but it is about ensuring that we are protecting American interests,” she told Face the Nation, “and that we are a leader in terms of the rules of the road, as opposed to following others’ rules.”

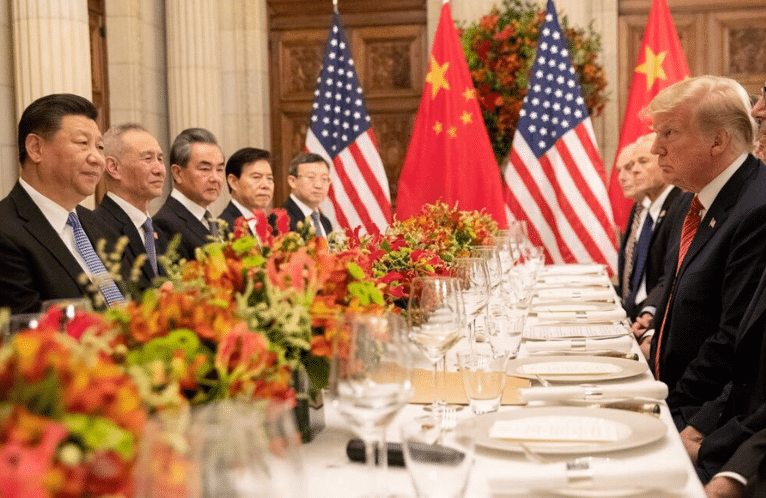

Donald Trump, on the other hand, speaks in equal turn of the brilliance of Xi Jinping and his desire for a “good relationship with China” and of the need to escalate the trade war he began in his first term. If Trump communicates a stable message to his supporters on China, it’s that China has taken advantage of the United States. It should be made to pay an economic price to balance the books and to prevent it from replacing America as the dominant global power. Ultimately, Trump’s tendency to dismiss Democrats’ human rights concerns in favor of economic issues puts him close to Chinese people’s understanding of the U.S.-China rivalry even as it reinforces the rivalry itself.

Lest it be argued that American attitudes come from a lack of information, even in policy expert outlets the impulse to see China as an outright enemy isn’t uncommon. Claims now circulate that China, along with North Korea, Russia, and Iran, is part of a new axis akin to that of Germany, Italy, and Japan in World War II. More frightening, in the face of this threat, the United States, it’s said, should keep the nuclear option on the table. If not, it could not protect its Pacific allies from Beijing.

If the ‘China consensus’ finds such wide expression throughout American society, if opposition to China and support for the U.S.-China rivalry has genuine American grassroots, regardless of its origin, it seems worth asking what exactly is the view from the other side of the Pacific? Is there grassroots support for the rivalry in China? A new poll from Tsinghua University’s Center for International Strategy and Security has the answer, and it is a resounding “Yes”.

U.S.-China Relations According to Chinese People

The Center for International Strategy and Security (CISS) was founded in 2018. It’s a think tank that aims to produce research-backed policy suggestions in China and communicate China’s positions internationally. The Carter Center’s China Focus met with CISS and its director, Da Wei, in October. Their latest poll is a sequel to a similar project conducted in 2023.

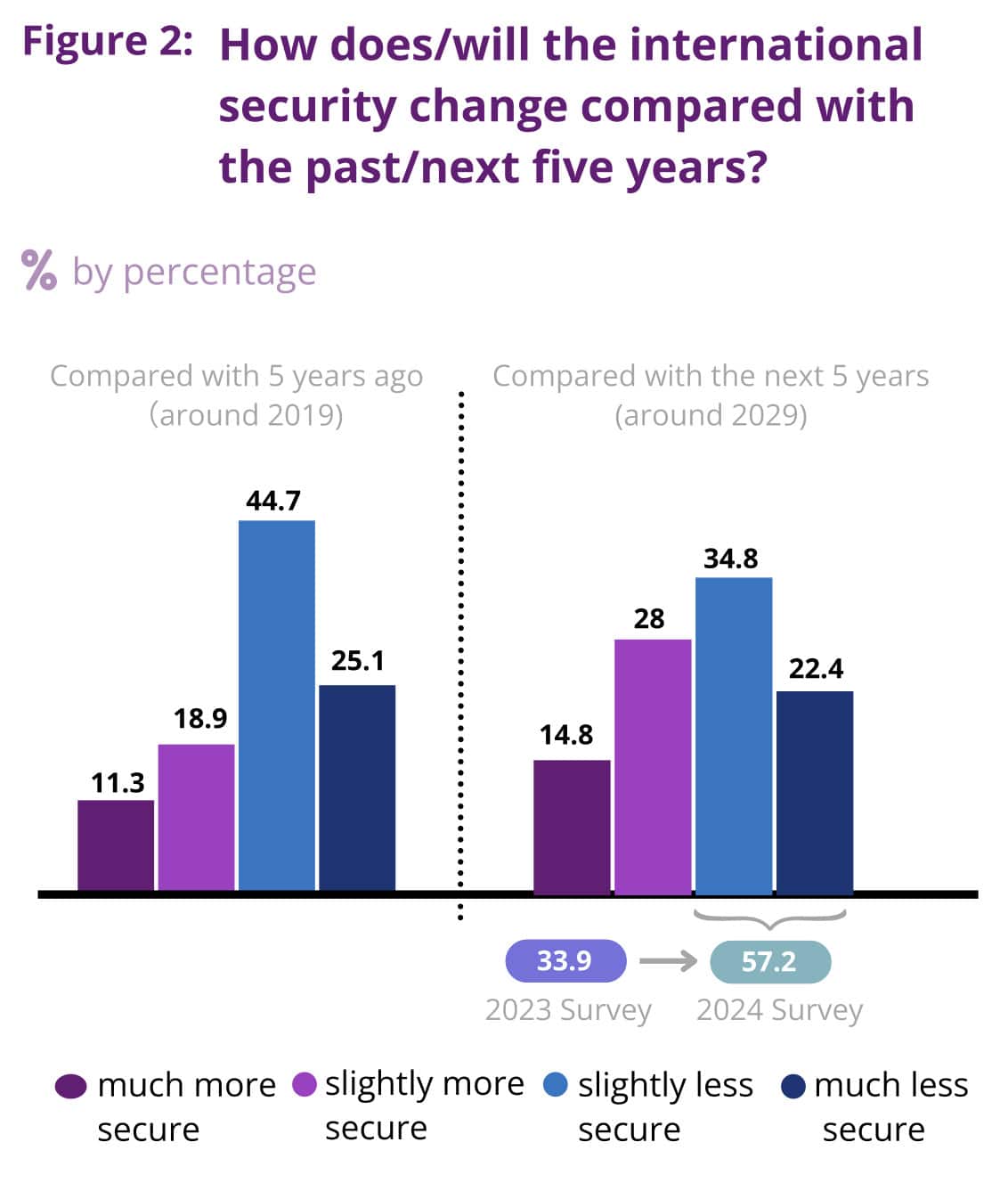

In general, the most recent survey found that a majority of Chinese people (69.8%) felt the world was less secure now than five years ago. Over half (57.2%) felt that the world would be even less secure in 2029. In 2023, this figure was 33.9%, meaning that concern over the possibility of global conflict has risen sharply. How respondents defined security, however, is less clear. In the 2023 survey, the plurality of respondents defined security as a stable economy and no war. The second largest category added no “large-scale uncontrollable man-made risks and ideological conflicts” to this definition. This question wasn’t asked in the 2024 survey.

If this concept of security (the enmeshment of economic development and peace) holds for 2024, then the grassroots of the U.S.-China rivalry begin to emerge. CISS reported that 76.8% of Chinese people believe “China is secure currently in the international environment.” Yet, 87.6% believe the United States is trying to contain China’s economic growth. In other words, if we can assume that economic development is a major part of how Chinese people define security (a reasonable definition for anyone), then the vast majority also believe at some level that the United States wants to threaten that security. In fact, when asked which element of U.S. global influence challenges China’s internal stability the most, 46.1% of respondents indicated the influence of U.S. economic policies on the international system. Only 34.5% indicated the U.S. military and its allies as the largest threat. Even fewer associate this threat with America’s promotion of human rights and democratic values. For Chinese people, the rivalry isn’t about political systems.

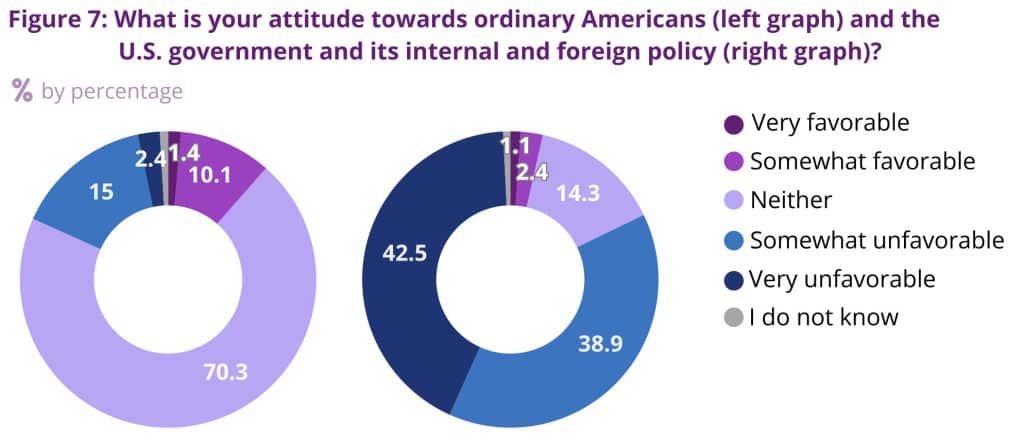

The blame for this threat seems to be placed at the feet of the U.S. government. Most respondents (70.3%) reported neutral attitudes about ordinary Americans while 81.4% held unfavorable views on the U.S. government’s domestic and foreign policy.

Whether Chinese people believe U.S. global influence has changed is unclear. Certain questions indicate that both the U.S. and Chinese influence have increased over the past year. Others indicate that China’s influence has increased at the expense of U.S. influence. The important pieces for demonstrating popular support for the U.S.-China rivalry on both sides, however, is clear.

Given the predominant interest among Chinese respondents in U.S. economic power and efforts to contain China’s economic development and the threat Americans see in China’s economic rise, we may no longer be in a world where is it appropriate to talk about misperceptions on either side of the rivalry. The challenge facing those who would like to see a more progressive approach on both sides is that both sides perceive each other accurately.

What Posture Should China Assume Toward the World?

Respondents to the CISS poll believed that globalization had brought more advantages to China (64.6%) but also believed that domestic affairs were more important than foreign policy (64.3%). Despite this, the overwhelming majority in 2023 (78%) and 2024 (73%) wanted China to assume a more proactive foreign strategy over the next ten years. It is not a position that will sit well with the 49% of Americans who recently told Pew that “limiting the power and influence of China” should be the United States’ top priority.

Consistent with the importance Chinese respondents placed on economic development, many respondents (41.9%) indicated that the economy was the most important force for realizing China’s foreign policy goals. The military came in second (30.6%) followed quite distantly by diplomacy (11.5%) and culture (10.4%). If disagreements emerge between China and other states, the plurality of respondents (41.9%) preferred that China rely on its own resources to settle the matter. Fewer (33.1%) supported reliance on institutions like the United Nations while the smallest category (25.1%) supported cooperation with China’s allies alone.

In terms of security threats, respondents continued to place the United States at the center. The highest ranked threat was international forces intervening over Taiwan, followed closely by the U.S.-China rivalry, international economic crisis, industrial and trade decoupling, artificial intelligence, and international intervention in the South China Sea. While pandemics ranked as one of the two most pressing security threats for survey respondents in 2023 (tied with territorial disputes), concern shrank in 2024. Biosecurity and pandemic threats are still perceived as more pressing than climate change or an arms race, but less important than U.S.-China relations and foreign intervention in Taiwan and the South China Sea. This suggests that, like other nations, China has begun to recover from the trauma of COVID-19, leaving room for other security risks to appear more threatening.

Although it risks returning to the realm of whether kittens are cute, it may still be worth stating the discrepancy between Chinese respondents’ belief that China itself is secure and the high risk they see in international intervention over Taiwan. Perhaps the logic is that prior to unification, conflict over Taiwan does not count as a conflict directly against China.

In all, the picture is one where China has benefited greatly from its integration in the global economy, and it should use its economic power to resolve its international disputes. Although domestic issues take precedence, Chinese people want China to be more assertive in international relations and to rely on its own strength to do so.

The Grassroots of the U.S.-China Rivalry

Opinion polls are weak instruments for answering ‘why’ questions. Why are Americans so unfavorable toward China? Why are Chinese people so unfavorable toward the U.S. government (and apathetic toward Americans)? The answers to these questions require qualitative analysis of the recent history of the bilateral relationship. What the polls do demonstrate, however, is popular support for the U.S.-China rivalry, and that is a problem.

Popular mutual distaste between the United States and China is a major obstacle to tackling the biggest problems facing the Earth today. The last four decades of U.S.-China cooperation resulted in important scientific and public health breakthroughs with positive global results. Combating climate change will also require collaboration between the world’s largest economies, which will remain all the more difficult the more their publics participate in the bilateral rivalry. The same is true for agreements on nuclear weapons.

The argument has been made for a while now that the U.S.-China rivalry strengthens authoritarianism, militarism, and nationalism on both sides. Polling shows populations on both sides see the rivalry as an economic struggle that could turn into a military conflict. It also shows deep investment among the populations on both sides into their governments’ participation in the rivalry. The upshot is that at this point the U.S.-China rivalry is reproducing itself backed by popular support.

It is not a reassuring lesson, and more work needs to be done to find areas of opportunity where tensions can begin to decrease. (Stay tuned to China Focus and the U.S.-China Perception Monitor for our own poll coming soon.) Nonetheless, a sober comparison of CISS’s recent findings with those of U.S. institutions is necessary. For now, that comparison seems to show that we are no longer in a world of misperceptions. Both sides perceive the rivalry in similar terms. For researchers and policy advocates, the task now is to determine how much of this shared, popular opinion is the result of misleading and paranoid political messaging and how much is a response to global problems that would be better solved through collaboration. There is much work to be done.

Nick Zeller is editor of the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and a senior program associate at The Carter Center’s China Focus iniative.

Miranda Wilson is a contributing editor for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.