How Capable Are the U.S. and Japan of Intervening in a Taiwan Conflict?

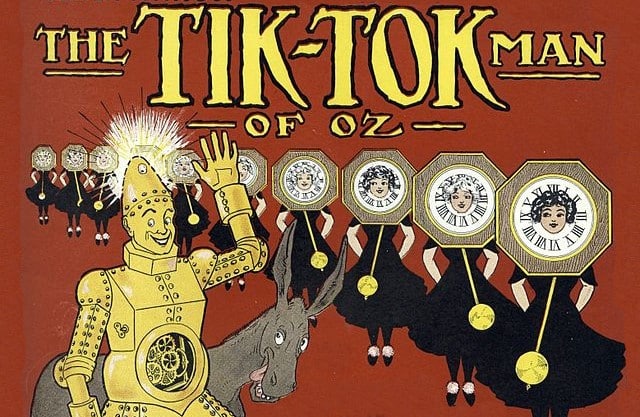

Banning Tik Tok Makes the U.S. Less Safe

- Analysis

David Fields

David Fields- 11/04/2024

- 0

Sometime next month a federal court will rule on the legality of banning TikTok in the United States if it is not sold to an American company as required in the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act. This act was passed by the U.S. Congress with significant bipartisan support and signed by President Biden in April 2024.

Anxiety over the Chinese-owned video sharing app is so high that it appears to be one of the few issues that can bring Republicans and Democrats together, and not just in Washington. More than 30 state governments controlled by both parties have enacted bans on the app in advance of the U.S. federal ban. Dozens of universities—including my own—have followed suit, though are still happy to use the platform for promotional purposes.

Such an alleged dire threat to the United States should be sparking a broad ranging conversation about what personal data can be harvested from American citizens and how this data should be stored and used. That is not what is happening. Instead, our leaders are banning TikTok because it is Chinese-owned. As most policymakers readily admit, it is not what TikTok has done, it is what it might do—share Americans’ personal data with the Chinese government and use that data for malign purposes. Essentially, TikTok is a security risk because of its national origins.

Such a policy is historically ill-informed, self-defeating, and feeds a growing and dangerous narrative among Chinese nationalists.

Basing the threat perception of a company on its national origins is a classic blunder—as especially American intelligence officials should understand. It was just this sort of thinking that led dozens of countries, militaries, and banks around the world to entrust their encrypted communications to a Swiss firm named Crypto AG. Little did they know that after 1970 this discrete company from famously neutral Switzerland was jointly owned by the Central Intelligence Agency and West German Intelligence (BND), who collaborated to ensure “backdoor” access to the firm’s encryption machines. According to an internal CIA report obtained by the Washington Post, this program, called RUBICON was the “intelligence coup of the century.”

The lesson of RUBICON should be clear: national origins are not a reliable indicator of whether any technology is safe. Either American security officials have a reasonable ability to detect backdoors in such technology or they do not. If they do, there is little to fear from a Chinese company. If they do not, any app or piece of hardware may be a threat, regardless of whether it is made in China, Switzerland, or the United States.

Understanding this makes plain how self-defeating these bans on TikTok, WeChat, and Huawei are, as well as how erroneous is the concept of “friend-shoring”—routing supply chains of sensitive technology through “friendly countries” to the exclusion of China. The United States should be investing in capabilities to counter threats in sensitive technology and in laws that govern the use of Americans’ personal data. All applications that harvest personal data should be scrutinized, as well as all types of hardware that undergird critical infrastructure. Laws governing data use should apply to all companies that trade in such data, regardless of national origin. The practices of all social media platforms should be analyzed for efforts by malign actors to influence public opinion.

Unfortunately, our fixation on Chinese threats seems to be hindering this broader conversation and focusing our attention in the wrong direction in a 21st century version of techno-McCarthyism. It is worth remembering that the McCarthyism of the 1950s was not only antithetical to American values, it was also an ineffective method of counter-intelligence. In a strict factual sense, McCarthy was not wrong: there were communist spies within the US Government. The problem was, he had no idea how many or who they were. So while he was whipping up anti-communist hysteria, harassing college professors (including University of Wisconsin historian William Appleman Williams), and hounding gay Americans out of government service, the British gentlemen Kim Philby, British intelligence liaison to the CIA, was quietly conducting the espionage that would make him such a hero in the Soviet Union he would get his own postage stamp there. Philby’s identity as a double agent would not be revealed until years after he left Washington, D.C. The mass hysteria and suspicion raised by McCarthy almost certainly made it easier for Philby to operate.

Similar dynamics are in play today. As the American leaders hype the Chinese threat, the United States is still without a single national data protection law governing the collection and use of Americans’ data. In this wild-west environment, dozens of firms amass oceans of data on U.S. citizens and companies. A general carelessness and lack of regulation has led to data leaks that are invasions of privacy (such as a photo of a person on a toilet taken by their Roomba being posted on Facebook) or threats to national security (the 2018 case of the fitness app Strava outing what was a secret American military facility in Afghanistan).

Our leaders’ focus on TikTok has drawn attention away from this very serious problem and done nothing to fix it. If the Chinese government wants to amass data on American citizens, there is nothing stopping them from buying it right now on an open market

Finally, such bans feed a very dangerous hyper-nationalist narrative in China, that it is not the behaviors of the PRC or Chinese firms that Americans object to, but to the rise of China itself. For me, as a historian of US-East Asian relations, this is eerily similar to one of the main causes of the deterioration of relations between the Japanese Empire and the United States prior to World War II. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Japanese leaders interpreted various developments from the 5:5:3 tonnage ratio at the Washington Naval Conference to the League of Nations condemnation of their invasion of Manchuria as attempts by the United States and its allies to keep Japan down. Many Japanese felt the United States—was changing the rules of geopolitics just as the Japanese were starting to win.

Similar forces are at work in US-China relations right now. For decades free-trade, globalization, and interconnectedness were the hallmarks of an American-led international order. Many developed economies benefited from this order; China perhaps most of all. To the Chinese it appears that the United States is changing the rules of the game now that China is becoming a serious competitor. The burden on American policymakers is to convince the Chinese leadership that it is their actions—repression in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, aggressive actions in the South China Seas, the theft of intellectual property, subsidies of state-owned firms—that are objectionable, not the rise of China itself.

Convincing the Chinese leadership of this may not be possible, but our current policies are certainly not sending this message. They are also doing nothing to make us safer.

David Fields is Associate Director of the Center for East Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Exceptionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019) and the editor of The Diary of Syngman Rhee, (published by the Museum of Contemporary Korean History, 2015,) and Divided America, Divided Korea: The US and Korea During and After the Trump Years (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.