Japan’s Prime Minister Takaichi Finally Says Something Close to What Beijing Wants to Hear

Sitting down with Jessica Chen Weiss

- Interviews

Yawei Liu

Yawei Liu  Juan Zhang

Juan Zhang- 10/05/2023

- 0

Jessica Chen Weiss is the Michael J. Zak Professor for China and Asia-Pacific Studies in the Department of Government at Cornell University. From August 2021 to July 2022, she served as senior advisor to the Secretary’s Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. State Department on a Council on Foreign Relations Fellowship for Tenured International Relations Scholars. She studies Chinese politics and foreign policy, focusing on the connection between domestic politics and foreign policy, particularly nationalism and public opinion.

You were an intern at The Carter Center as an undergrad at Stanford. Could you tell us if that internship made any difference to your career?

Jessica Chen Weiss: It was a great experience, especially for somebody just starting and trying to understand and learn more about China. For me, the biggest takeaway of that internship is that there was and still remains much room for China’s future evolution in ways we can’t necessarily foresee. It was fascinating to see the local (election) experimentation at that time. Of course, it didn’t go very far, but I had the chance to accompany Ministry of Civil Affairs officials to a village election site and a county level training.

That summer was my first exposure to living among ordinary Chinese people. I was in Baoji (Shaanxi) and then Chengdu (Sichuan). The food there was so spicy. I think I lost five pounds that week. I didn’t know what to eat for breakfast because it was all covered in red oil. The whole experience of being there that summer was phenomenal, just to be there working amongst Chinese colleagues.

Taking a big step back, so much of what is missing in the American conversation about China is the complexity and aspirations of those living inside China. That summer working for The Carter Center gave me an early opportunity to live and work among others in China.

You served as a senior advisor at the State Department at the beginning of the Biden administration. Has this changed your view of the U.S.-China relationship? In what way has it impacted your scholarship?

Jessica Chen Weiss: I would say that my time at the State Department had a big impact on my sense of just how dangerous the deterioration in US-China relations has become. In addition, this relationship is not just bilateral; it is a relationship that is likely to have global impact and is felt across the whole world. I had grown more concerned about the trajectory of US policy toward China under the Trump administration. But, by being in the Biden administration, I better understood the continuities, the differences, as well as what still has yet to be worked out. Academics tend to try to understand and explain what is and spend less time thinking about what should be.

Most policymakers focus on what they should do and what they are aiming at. This has oriented my thinking now toward a bit more of a forward-looking exercise, to examine on what terms the U.S. and China can peacefully coexist and if they are able to come up with a new framework to manage the relationship. I feel there is a lack of imagination and too much pessimism and even fatalism on both sides.

It’s not to say that it will be easy to identify. In part, there’s a lot of wrangling and jockeying over what that would look like. Still, the failure to articulate and imagine what such a coexistence could look like to benefit both societies makes it harder to see the costs of the current emphasis on preparing to fight and win in a protracted competition.

Professor Kiron Skinner, then Director of Policy Planning at the State Department in the Trump administration, indicated that the great power competition with China was “a fight with a really different civilization and a different ideology, and the United States hasn’t had that before.” Do you feel there is an undercurrent of a racial factor in the United States when assessing China’s intentions and capabilities?

Jessica Chen Weiss: I was also pretty shocked when I heard that remark by Kiron Skinner. I wrote a piece at the time in the Washington Post Monkey Cage criticizing her remarks, and she reached out to me. When I was in DC, I went to see her. She was quite upset to have been criticized, but I got the sense that there wasn’t a lot beneath it, that this was an off-the-cuff comment that wasn’t grounded in a deeply racialized view of the world.

I would say that working in the Biden administration, I never felt that racial animus ever was beneath the surface shaping policy. If anything, the administration was quite clear that anti-Asian racism was unacceptable. In particular, it was important to use words and language like the PRC instead of China to avoid phrases that might inadvertently implicate Chinese Americans or people of Chinese descent.

That said, I don’t think we can completely reject the role of racial consciousness in shaping the public conversation about China, even though representatives of both parties have said that we need to distinguish between the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese people, and this should not be allowed to target or victimize Americans of Asian descent arbitrarily. Nonetheless, some prominent commentators and former officials have used metaphors that dehumanize or portray China in less than fully human terms. We know from scholarly research and the uptick in anti-Asian racism and violence in the United States that those words have meaning. What a politician says has real consequences, even if they didn’t intend for that kind of harm. However, you might wonder whether there is some degree of dog whistling going on, but even if they didn’t intend it, how their words are interpreted still matter a lot.

I do worry that such language contributes to our collective difficulty imagining coexistence. There are many factors here, including differences in political systems, values, and religion, not to mention security and economic differences and concerns. But I worry that highlighting these racial and ethnic differences exacerbates the challenge of appreciating the humanity in another country. Again, I’m not resigned to that. I think that the importance of race as a factor can be augmented or diminished. It’s really important that leaders, whether they’re in office or out of office, and public opinion leaders, pay great attention to ensuring that this factor is minimized and that, in particular, efforts to protect national security and intellectual property do not come at the expense of Americans’ civil rights, no matter whether they look Chinese.

You argue that containment of China by any means necessary could undermine what the United States has always stood for, weakening U.S. leadership in values, its vitality as a democracy, and its ability to attract talent. And U.S. foreign policy also risks suffering from an unhealthy focus on China as a threat. So, from your view, what kind of relationship should the U.S. have with China? Given China’s current strength, can the U.S. win against China while fully adhering to its values and principles?

Jessica Chen Weiss: I applaud the Biden administration’s efforts to resume high-level diplomacy and seek cooperation where interests align. However, I am concerned that the overarching strategy, centered on outcompeting China, inadvertently promotes a zero-sum mindset. This could lead people in the United States and China to view our efforts as an attempt to win at China’s expense. In my view, competition, a term I don’t particularly favor, is here to stay. However, it must be managed within a framework of peaceful and constructive coexistence. This framework should include clearly defined boundaries that determine what actions are permissible and what are not, with both sides committed to safeguarding their interests without harming the other party. Those are sometimes referred to as guardrails. However, when the goal is to beat the other party, as we have seen, there’s not very much interest in the Chinese side in establishing guardrails. These are often seen in China as seeking to tie China’s hands or maintain a status quo that favors America at China’s expense.

I would say that an important adjustment in the collective national conversation in the United States is to consider how to mitigate the risks associated with continued economic, technological, and scientific exchange and preserve the benefits for Americans and American national interests. Too often those interests are seen as liabilities, dependencies, things that could be exploited. Still, some of these ties continue to be essential to American interests, whether that’s in developing affordable cancer drugs or decarbonizing the economy and fighting climate change. In many cases, there’s a lot of scientific expertise and know-how in China, not to mention their advanced manufacturing, that makes it very difficult for us in the United States to achieve our own interests and objectives without some degree of participation from Chinese firms, scientists, and entities.

Then there’s also, I think, the important role that some degree of continued integration plays in deterrence—drawing on the fact that the Chinese leadership has not just a desire to “reunify” with Taiwan but also to modernize and develop China into a world-class economy and global power. Part of that means China remains dependent on access to international technology and markets. If you take that away and preemptively reduce that interdependence, then that reduces the incentive of the Chinese government not to act more aggressively to pursue its other objectives.

You mentioned in your interview with Ezra Klein that China does want to reshape the international order to privilege the state over individual political rights. But that’s different from saying that China needs or wants to destabilize the international order and replace the United States as the sole global superpower. So, without threatening U.S. hegemony, do you think the U.S. should tolerate the Chinese attempt to reshape the international order? Do you think China will stop after it has achieved its goal of reshaping the international order?

Jessica Chen Weiss: It’s really important in thinking about China’s ambitions to acknowledge how little is certain and how much is subject to change with both opportunity and constraints. I think it’s pretty clear that the Chinese Communist Party does not feel secure in an order dominated by the United States, which has long privileged liberal values over and sought to, in many cases, transform less-than-democratic regimes like China’s. But we are in an important moment of flux in the international order. Although the Biden administration has recommitted to many of these multilateral institutions, there are many ways in which the United States itself is not as satisfied as it once was with key institutions like the World Trade Organization.

I would say that there is still a degree of overlap in the visions of the international order that both China and the United States could be satisfied with, and that really rests around the principles of the United Nations Charter and the sovereignty of nation-states. That is a world in which there’ll be a little bit less liberal intervention, but that’s also something that, frankly, many in the United States are increasingly coming to realize has not been as effective as Americans once hoped, especially the use of American military power to build and secure democracy in societies that don’t see it as homegrown.

I think that there is actually space here, although it’s an uncomfortable one. It requires recognizing that a world safe for diversity is one in which we can have systems of government that don’t look like each other. That phrase was from President JFK in the early days of the Cold War. While we may not ever be happy with or likely to congratulate leaders of different types of systems whose values Americans disagree with, a world that’s safe for democracy may also require a world that is somewhat also safe for autocracy. This consideration arises due to the escalating interference we’ve witnessed in recent years, primarily from Russia but also increasingly involving other authoritarian actors.

In your New York Times op-ed, “Even China Isn’t Convinced It Can Replace the U.S.,” you write, “China’s long-term ambitions are difficult to know with certainty, and they can change. But it is far from clear that it can — or even seeks to — replace the United States as the world’s dominant power.” Do you think there is a growing possibility of a “clash of perceptions”, i.e., Chinese elites believe the U.S. is in irreversible decline and can be pushed out of Asia and American counterparts feel China poses an existential threat and has to be contained? How can we stop this clash from storming into the bilateral relationship?

Jessica Chen Weiss: I think that danger has been substantially reduced in the last 12 to 18 months as China has encountered its own economic headwinds domestically, and the United States, while still in the midst of a very contentious political drama, has nonetheless managed to pass some important legislation and get the economy back on track. There’s certainly a possibility for misperception. But this one is not one that I am concerned about. I’m more concerned about the possibility that Chinese leaders think that the United States is supporting Taiwan independence, and that therefore the Chinese leadership concludes that they must act to deter further steps toward permanent separation or independence. That’s a very specific misperception that I think is important to correct.

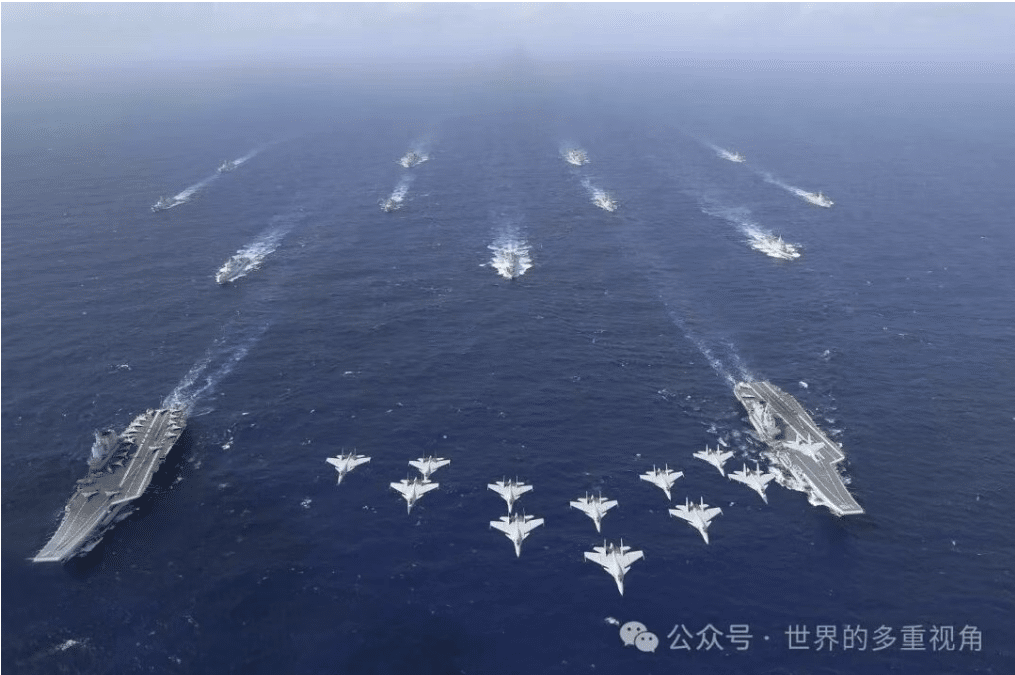

In your Foreign Affairs essay “Don’t Panic About Taiwan”, you say, “Alarm over a Chinese invasion could become a self-fulfilling prophecy.” You do not believe a Chinese invasion is imminent. Why do you think many in the U.S. military, security, and intelligence community keep pointing to a specific time that China will launch an invasion? What do you think is the best approach to manage volatile cross-strait relations so they do not trigger a U.S.-China conflict?

Jessica Chen Weiss: I think there are a number of different factors at work here. I’ll name three. One is that in both China and the United States, leaders — particularly military planners — are preparing for contingencies that they feel the other side might trigger. And their efforts to get ready, to be able, if necessary, to fight and defeat the other side, are then interpreted by the other side as evidence that maybe they’re planning to do something, that this is not a just-in-case kind of plan.

A second is that at least on the US side, and to some extent on the Chinese side, both militaries don’t feel they’re in fighting shape. There are doubts about certain vulnerabilities, and they are trying to get their systems in gear to focus on the challenge and do what has been hard for them in various ways.

The third is that they believe that only military readiness will be ultimately able to deter the other side. Unfortunately, this is a kind of pathology – the belief that only military capabilities and demonstrations of resolve will keep the peace. They don’t recognize, as some scholarly research has shown, and going back to Thomas Schelling (American economist and professor of foreign policy), that threats aren’t enough to deter. You need conditional threats and conditional assurances that the target will not inevitably be punished if it acts with restraint.

Even as each side continues to invest in its military readiness and ability to fight, they must also make sure that they spend equal time investing in the quality and credibility of their assurances that there still is an alternative to war, that this situation can be managed peacefully as it has for four, five decades. But I fear that this spiral of pessimism becomes a bit fatalistic without greater effort and attention to such assurances by all sides, not just the United States but also by Beijing and Taipei.

Many believe the US is actively encouraging elements in Taiwan to move toward independence. What do you think of this? Is there an eventual compromise that can work out between the US and China on the Taiwan issue?

Jessica Chen Weiss: I think that America’s longstanding position that hasn’t been repeated much recently was that the US would support any outcome peacefully arrived at by both sides, that the US cares about the process, not so much about the outcome of the resolution of the dispute between the people on both sides of the Strait.

The administration is sincere and has been much more disciplined in recent months about stating that America’s interest is in peace and stability, not in any particular outcome in the Taiwan election, and certainly does not support Taiwan independence. Still, there is loose talk on Capitol Hill and among former Trump administration officials who would like to do much more with Taiwan, including offering Taiwan US diplomatic recognition. The United States could, under the Biden administration, repeat what has been said before in terms of encouraging dialogue between the two sides. And while the United States supports Taiwan’s participation in international organizations, it’s important to note that this support does not extend to support for recognizing Taiwan’s sovereign status, for instance. We rarely make clear that there are limits around American support for Taiwan. This goes back to my point about the role of assurances being critical to bolstering deterrence, which colleagues and I have written about for Foreign Affairs.

You have written extensively on what Americans should and could do to stabilize the relationship. If you were invited to a small discussion with Chinese foreign policy experts, and they asked you to share your view on fixing the bilateral relationship, what would be your advice to the Chinese elite on what China should do to prevent this relationship from veering into zero-sum rivalry, if not outright conflict?

Jessica Chen Weiss: First, it’s very important to recognize that it takes two to tango and that it’s not on one government to repair the relationship in the current atmosphere of mutual mistrust. Unilateral concessions are unlikely and potentially risky. Nevertheless, I believe the Chinese government has important decisions to make regarding its global relationships, extending beyond just its interactions with the United States. Demonstrating resolve won’t work unless accompanied by more convincing assurances. These assurances should convey that if the United States or other nations were to pursue a more conciliatory relationship with China, China would not exploit that restraint to its advantage.

They could start by recognizing that the emphasis on showing resolve has yet to gain China as much as the top leadership would’ve liked. Still, displaying greater signs of generosity, kindness, tolerance for differences, and a willingness to reach compromises would enhance China’s capacity to sustain its development and rise as a global power without inciting the formation of counterbalancing coalitions. Of course, the United States is working on this, but it’s doing so in the context of growing concern about China’s more coercive behavior. I would say this is the second point I would convey.

Another point is that efforts to enhance security, whether in the United States or China, often result in significant collateral damage. For instance, Chinese policies aimed at bolstering domestic security can have a chilling effect on the willingness of foreigners to visit China, conduct business in China, or pursue studies there. While ostensibly intended to protect China, measures such as the anti-espionage law and data laws may ultimately harm more than benefit Chinese interests. There are alternative ways to address potential political security concerns without resorting to such sweeping and chilling measures.

You are the author of Powerful Patriots: Nationalist Protest in China’s Foreign Relations. Given China’s political system, can this nationalism be channeled into something constructive and moderate if the top leadership of China is more open-minded and sensitive to the fact that stoking nationalist fire may also lead to the burning of its own house?

Jessica Chen Weiss: I think the Chinese government is well aware that nationalism could burn down the house and has therefore not allowed street demonstrations, which I researched and wrote about in my first book, since Xi took office. At the same time, I think the current approach has also undermined China’s global image by allowing the forces of online nationalism to run as rampant as they have been permitted to do. It’s not a very friendly image to project.

Additionally, this situation undermines the quality of discussions and debates on Chinese foreign policy and the choices that China faces. In China, public intellectuals often encounter a real sense of peril when expressing even moderately divergent views on how China should pursue its interests. While individuals in the United States, including scholars, may face some risks for voicing unpopular opinions, they seldom experience a personal vulnerability that extends to their physical safety and that of their families. In contrast, in China, that’s not necessarily the case.

Authors

-

Dr. Yawei Liu serves as a senior advisor to the Carter Center’s China Focus program. He is the founding editor-in-chief of U.S.–China Perception Monitor and its Chinese-language website, 中美印象.

-

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).