Translation: Xi Jinping on Literature, Art, and Politics after Tiananmen

- Other (Do Not Use)

USCNPM Staff

USCNPM Staff- 10/05/2022

- 0

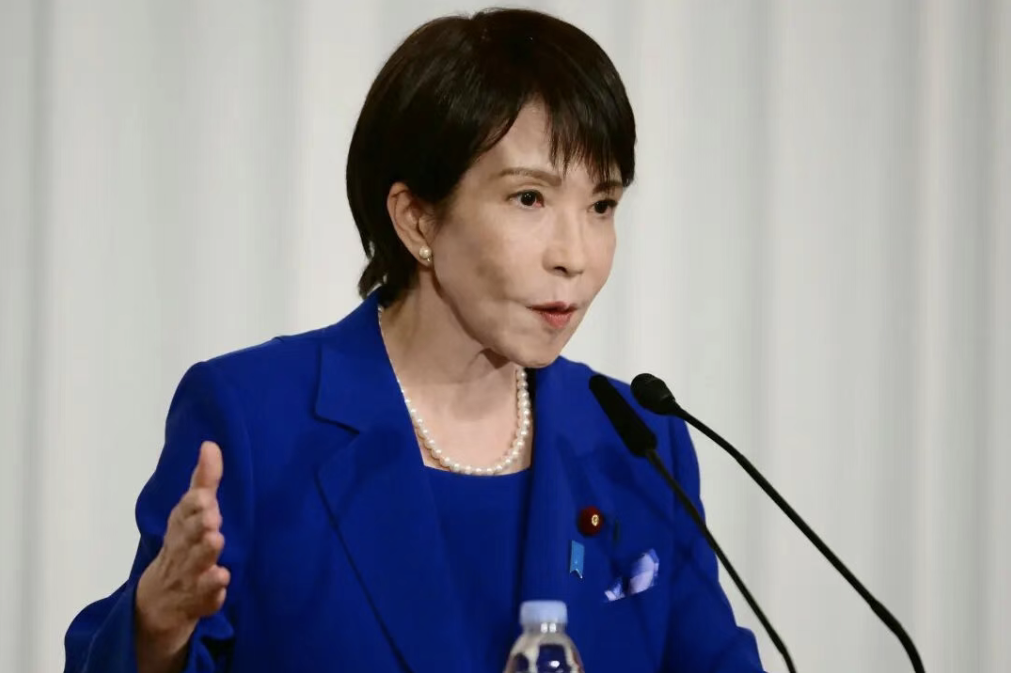

The following essay by Xi Jinping, then the Chinese Communist Party chief of Ningde, was penned shortly after the crackdown in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Washington Post reporter Eva Dou, who came across the essay in a Fujian library, writes how it hints at ‘how the first serious crisis of [Xi’s] career may have informed his worldview’.

In his sweeping criticism of the relationship between literature, art, and politics, Xi writes that, ‘We must oppose those who, under the guise of freedom of creation, use literature and art as a political tool to promote bourgeois liberalization, and repudiate the lines, directives, and policies of the Party and negate the leadership of the Party.’

In his reference to ‘foot washing and egg hatching’, Xi specifically critiques the China Avant-Garde exhibition at Beijing’s National Art Museum, where an incident involving a gun, as Alex Colville writes, ‘was instantly immortalized, swept up in the social and political hurricanes of 1989, and all the interpretations that came with it’.

Check out Eva Dou’s Twitter thread for more details on the essay.

Xi Jinping: On the Relationship between Literature and Art and Politics

论文艺与政治的关系

Xi Jinping

习近平

English

The relationship between literature, art, and politics is one of great importance. Dialectical materialism holds that the relationship between literature, art, politics can neither be separated nor equated.

Both belonging to the superstructures of society, literature, art, and politics are fundamentally determined by and have a reactive effect on the socio-economic foundation [of society]. As Engels says, ‘political, legal, philosophical, religious, literary, artistic, etc., development is based on economic development. But all these impact one another and also influence the economic base.’ Literature and art use images to reflect social life. Similar to philosophy and religion, literature and art, as Engels says, ‘are an ideology more remote from the material and economic base’; unlike politics and law, literature and art’s relationship with the economic base is not a direct one, but rather an indirect one. The economic base’s decisive impact on literature and art or the influence of literature and art on the economic base both demand ‘an intermediate link’ through other forms of superstructure such as morality, philosophy, and religion, though mainly through politics. This is because ‘politics is the most concentrated expression of the economy’ and maintains a dominant position among the superstructures. It holds the most direct and immediate relationship with literature and art. No matter how much influence progressive or reactionary literature has had on society, it must first be affirmed that the socio-political context of the time determines the creation of progressive or reactionary literature before such literature and art can influence society. There would have been no Enlightenment literature without the struggle of the French bourgeoisie against the feudal aristocracy; there would have been no new literature in China without the spectacular May Fourth Movement. Countless evidence affirms the inseparable relationship between literature, art, and politics.

On the other hand, the two—literature/art and politics—cannot be made equal lest one becomes eliminated. Comrade Mao Zedong, in ‘Talks at the Yan’an Symposium on Literature and Art’, maintains that ‘politics cannot be equated with literature and art, nor can a general worldview be equated with a method of literary and artistic creation and criticism’. Literature, art, and politics, belonging to the superstructures of society, holding relative independence and distinctiveness. Literature and art hold independent content, form, and process; it is a special sort of spiritual production with an irreplaceable function. As Mr. Lu Xun writes, ‘literature and art are both the fire emitted by the national spirit and the lamp that lights up the national spirit’s future’. Literary and artistic works greatly influence the national spirit, the social atmosphere, and the ideological and cultural tendencies of the next generation. High-quality literary and art works may inspire revolutionary ideals, shape the national spirit, and enlighten people’s wisdom and souls. Especially in the present era, literature and art hold the important duty to unite, inspire, and motivate the people to achieve the ‘Four Modernizations’, to revitalize China, and to build a conception of socialism with distinctive Chinese attributes. Such duty cannot be entirely transferred to politics. Marx has described the phenomenon of unbalanced development in literature and art and material production during certain historical epochs; artistic development carries its own laws—which are different from those of political and economic development—that ought to be obeyed when handling literary and artistic works.

Decades of practice have shown that the ability to correctly understand and handle the relationship between literature, art, and politics is the key to the prosperity of literature and art. And, to correctly understand and handle the relationship between literature, art, and politics requires the implementation of the Party’s literature and art policies and to oppose and overcome two biased viewpoints.

One viewpoint that must be opposed and overcome is that literature and art are equal to politics, thereby erasing their unique nature. This view completely deviates from or contradicts the law of literary and artistic development by integrating literature and art into political struggle, thereby constraining literature, and turning it into a replica of politics. This view facilitates and is the origin of turning literary and artistic creations into a formulaic, conceptualized process. It requires people to write about and discuss the core and to underscore the ‘theme’; it requires literature to follow a set model or to demonstrate specific policies and political slogans of different periods. This leads to the ‘falsity, grandiosity, and shallowness’ of literary and artistic creation. From creations consisting of slogans upon slogans during the Great Leap Forward to poetic competitions in Xiaojinzhuang Village, the situation of ‘eight theatrical plays for eight million people’ demonstrates that following such a path would not only dismember the special function of literature and art but would also destroy its proper role. Moreover, it will bring about the confinement of people’s thoughts and the suffocation of literary and artistic life.

Another point of view that must be opposed and overcome is the pursuit of pure art. This view promotes detachment from politics and reality. Literary and artistic works created with this prejudice are often difficult or pale because they are disconnected from life and politics. It will finally lead literature and art into the path of decay. As early as more than forty years ago, Mao Zedong pointed out: ‘Literature and art should be well established as an integral part of the whole revolution, as a powerful weapon for uniting the people, educating them, attacking and destroying the enemy, and helping the people in their struggle against the enemy’. In the revolutionary war years, literature, art, and politics were inseparable. In times of peace and construction, literature and art should also keep pace with the times. Because our literature and art are for the people and for socialism, they cannot be without ideals, goals, and social responsibilities. No matter how different the types and styles of our literary and artistic works are, they should have only one social effect, that is to arouse people’s sense of historical responsibility for national rejuvenation and social progress. They should promote the spirit of hard work and bravery, unity and struggle, and reform and innovation of the Chinese nation, and raise people’s national self-esteem and self-confidence. Numerous examples in the history of Chinese and foreign literature and art have proved that truly great literary and artistic works are always rooted in social and historical contexts. Many literary and artistic works on the theme of reform, such as Jiang Zilong’s ‘Factory Manager Qiao Gets to Work’ and He Shiguang’s ‘The Rural Market’, enjoyed a large readership because they reflected the political life of the time. Deng Xiaoping pointed out, ‘Literary and artistic creation must fully express the excellent qualities of our people. It should praise the great victories achieved by the people in revolution and construction, and in the struggle against all kinds of enemies and difficulties. The fundamental road to the prosperous socialist literary and artistic cause is to voluntarily plant oneself into the lives of the people, absorbing content, theme, plots, poetics and things to paint.’

To correctly understand the relationship between literature and art and politics, we must conscientiously carry out Mao’s ‘adopting ancient things for the current time and applying foreign things to our needs’ and ‘letting a hundred flowers blossom and letting a hundred school of thought contend’, and correctly grasp the relationship between the Party’s leadership and the development of literature and art. Deng Xiaoping said, ‘The Party’s leadership of literary and artistic work is not to issue orders, and not to require literature and art to be subordinated to temporary, specific, direct political tasks. Rather, the Party, in accordance with the characteristics and development laws of literature and art, helps literary and artistic workers obtain the conditions to continuously make literature and art prosper and to create excellent literary works worthy of the people and the times’. In other words, to exercise correct political leadership over literature and art, the Party must first conscientiously carry out the Party’s basic line of one central task (of economic construction) and two basic insistences (insisting on the four basic cardinal principles and insisting on reform and opening up). Second, we must fully respect the labor of writers and artists, fully respect the laws of literary development, and fully understand the needs of literature and art and literary workers, giving full play to the creative talents and creative spirit of individual literary artists. The function of literature and art should be properly estimated, and the issues of right and wrong in the field of literature and art should be analyzed and viewed in a realistic manner. We should advocate the free development of different forms and styles, and the free discussion of different viewpoints and schools in art theory. While advocating freedom of creation, we also expect all writers and artists with integrity and conscience to unite to create works that directly serve the people and socialism for the sake of social progress and national stability. It is wrong for anyone to take an irresponsible attitude towards life and society. We must oppose those who, under the guise of freedom of creation, use literature and art as a political tool to promote bourgeois liberalization, and repudiate the lines, directives, and policies of the Party and negate the leadership of the Party. It is not advisable to use literary works as catharsis tools. For a period of time, porn books and videos have flooded society, and literary works of low taste have flooded the literary market. Some time ago, foot washing and egg hatching were on display in the National Art Museum of China, and they were called “behavioral art” representing the new trend. In essence, they desecrated art and destroyed beauty.

At the same time, we should actively promote and develop healthy and active literary and artistic criticism, and we should advocate competition for works of different styles, forms, and genres. We should encourage the debate of various views on literary and artistic issues. In literature and art criticism, newspapers and periodicals should truly carry out the ‘let a hundred flowers blossom campaign’, adopt a fair attitude, and form a healthy, democratic atmosphere of mutual respect and equal discussion. Party Committees at all levels should carry out the Party’s lines, principles, and policies concerning literature and art in an exemplary manner, strengthen exchanges and discussions with writers and artists, and make regular presentations to them, while also listening to their opinions and requests. We should do our best to provide them with the necessary help for their deep understanding of social life and their engagement in literary and artistic creation. We should both adhere to our principles and refrain from interfering across the board. But we cannot ask the Party and the government not to interfere in literature and art at all, or to ignore specific works at all. In fact, the government and ruling party of any country cannot completely do nothing to intervene in literature and art or ignore specific works at all. The difference lies only in the scope and standard of intervention, and the particular way of intervention. What matters is not how much or how little to regulate, but what principles and directions to apply when engaging in regulation. We are a socialist country guided by Marxism. The Party’s guidance of literature and art should adhere to the Party’s Four Cardinal Principles (we must adhere to the socialist road, the people’s democratic dictatorship, the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought), and we should focus on maintaining the overall political direction. Specific views and comments on literary and artistic works should be judged by the masses and literary and artistic experts through normal democratic discussion. We must trust the artistic appreciation and aesthetic ability of the people. To deal with contradictions and disputes in academia and art, we should avoid administrative orders as much as possible, and learn to deepen our understanding and improve our artistic level through democratic and equal discussion. What is correct should be promoted and what is incorrect corrected through the development of sound material and cultural conditions and an appropriate public opinion environment, and through the formulation of regulations and laws. Only in this way can we promote the healthy development of literature and art.

中文

文艺与政治的关系是一个十分重要的理论问题。辩证唯物主义认为,文艺与政治的关系即不可割裂,又不可等同。

文艺与政治同属社会的上层建筑,归根到底是由社会的经济基础所决定并对经济基础起反作用。思格斯说“政治、法律、哲学、宗教、文学、艺术等的发展是以经济发展为基础的。但是,它们又都互相影响并对经济基础发生影响 ”。文艺以形象反映社会生活,它同哲学、宗教一样,是思格斯所说的“更远离物质经济基础的意识形态”,它和经济基础的关系,不是象政治、法律那样直接的,而是间接的。无论是经济基础对文艺的决定作用,还是文艺对经济基础的反作用,都总是要通过其他上层建筑的“中间环节”,如道德、哲学和宗教等,而主要通过政治。因为“政治是经济的最集中的表现”,在上层建筑中处于主导地位,它与文艺的关系也最为直接最为密切。无论进步或反动的文艺对社会产生了多大的影响,首先还得肯定,是当时的政治背景和社会生产决定了这种文艺的生产,然后才有文艺对社会的反作用。没有十八世纪法国资产阶级对封建贵族的斗争,就没有启蒙文学的存在;没有波澜壮阔的“五四”运动,中国新文学也无从产生,无数事实印证了文艺与政治有着不可割的裂(sic)关系。

另一方面,又不能使二者互相等同,取消其中的任何一方。毛泽东同志在《在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话》中指出:“政治并不等于艺术,一般的宇宙观也并不等于艺术创作和艺术批评的方法”。文艺与政治一样,作为上层建筑的一个领域,有其相对独立性和特殊性。它有独立的内容、独立的形式和独立的运动过程,是一种特殊的精神生产,有着其他任何东西所无法替代的特殊功能。鲁迅先生说“文艺是国民精神所发出的火光,同时也是引导国民精神的前途的灯火”。文艺作品对与国民精神、社会风气乃至下一代的思想文化素质都具有巨大的熏陶渐染、潜移默化的作用。高质量的文艺创作,具有激发革命理想、铸造民族灵魂、启迪人们智慧、美化人们心灵的作用。尤其在当今时代,文艺担负着团结、鼓舞和激励人民,为实现四化、振兴中华、建设有中国特色的社会主义而英勇奋斗的重任。这种作用是政治不可能完全取代的。马克思曾经论述过一定的历史时期艺术的繁荣与物质生产发展不平衡的现象,艺术的发展有其不同与社会政治、经济发展的特殊规律,应当遵循这种规律来对待文艺工作。

几十年实践证明,能否正确理解和处理文艺与政治的关系,是文艺能否繁荣的关键。而正确理解和处理文艺与政治的关系,就必须贯彻落实党的文艺方针政策,反对和克服两种片面观点。

必须反对和克服的一种片面观点认为,文艺同于政治,谋杀文艺的特殊性。它完全偏离或违背文艺自身的发展规律,把文艺彻底纳入政治斗争的轨道,使之成为政治的翻版束缚文艺的手脚。这种观点是文艺创作公式化、概念化的思想来源。它要求人们写中心、论中心,强调从“路线出发”、“主题先行”,要求文艺依样画葫芦或图解具体的政策和不同时期的政治口号。从而导致了文艺创作的“假、大、空”,从大跃进时期标语口号式的作品,到天津小靳庄的群众赛事,乃至出现“八亿人民八个戏”的局面,都证明沿着这条胡同,不仅使文艺的特殊功能被肢解,应有作用被破坏,更可悲的是还将带来人民思想的禁锢和文艺生命的窒息。

必须反对和克服的另一种观点是追求纯艺术,宣扬脱离政治,远离现实,躲在象牙塔中鼓吹为艺术而艺术。持这种偏见所创作的文艺作品往往因生活源泉的枯竭和政治力度的欠缺而显得朦胧艰涩或苍白荒唐。它同样会把艺术引入衰亡的歧路。早在四十多年前,毛泽东同志就指出:“要使文艺很好地成为整个革命机器的一个组成部分,作为团结人民、教育人民、打击敌人、消灭敌人的有力武器,帮助人民同心同德地和敌人作斗争。”在革命战争年代,文艺和政治是密不可分的。在和平建设时期,文艺也应该紧扣时代的脉搏。因为我们的文艺是为人民的文艺,是为社会主义的文艺,它不能无理想、无目标、无社会责任。无论是批判陈规陋习,还是讴歌时代精神,无论是揭露消极丑恶现象,还是赞颂英雄壮举,无论是回顾和思索历史,还是展望憧憬未来,无论我们文艺创作的品种和风格多么不同,其社会效果应该只有一个,那就是唤起人们对民族振兴和社会进步的历史责任感,弘扬中华民族勤劳勇敢、团结奋斗和改革创新的精神,提高人民的民族自尊心和自信心,以崭新的风貌屹立于世界民族之林。中外文艺史的无数事例证明,真正伟大的文艺作品,总是植根于社会沃土,充满了时代气息,回荡着历史足音,深刻反映一定时期的社会政治内容。以新时期的文艺创作为例,无论是悼念周总理的天安门诗抄,还是尔后出现的“伤痕文学”、“寻根文学”,都以其对政治的深切关注,在人民群众中引起强烈的反响。无怪乎,人们把天安门诗抄称之为意志的组合,信仰的组合,民心的组合,党心的组合。因为它是人民不息的吼声,时代不朽的音符,使文艺的社会效应达到了前所未有的强度。许多表现改革题材的文艺作品,如蒋子龙的《乔厂长上任记》、何士光的《乡场上》等,之所以拥有众多的读者,就是因为它们面对共同的时代主题,唤醒民众的主体意识,是政治生活的折射和改革的风云录。邓小平同志指出:“文艺创作必须充分表现我们人民的优秀品质,赞美人民在革命和建设中,在同各种敌人和各种困难的斗争中所取得的伟大胜利。”“自觉地站在人民的生活中吸取题材、主题、情节、语言、诗情和画意,用人民的创造历史的奋发精神来哺育自己,这就是我们社会主义文艺事业兴旺发达的根本道路。”

正确理解文艺与政治的关系,要认真贯彻毛泽东同志提出的“两为”和“双百方针”,正确把握党的领导和发展文艺的关系。邓小平说:“党对文艺工作的领导,不是发号施令,不是要求文学艺术从属于临时的、具体的、直接的政治任务,而是根据文学艺术特征和发展规律,帮助文艺工作者获得条件来不断繁荣文学艺术事业,创作出无愧于我们伟大人民、伟大时代的优秀文学作品和表现艺术成果。”换言之,党对文艺实行正确的政治领导,首先要认真贯彻党的基本路线,坚持一个中心两基本点。其次要充分尊重作家艺术家的劳动,充分尊重文艺发展的规律,充分理解文艺和文艺工作者的需要。要充分发挥文艺工作者个人的创造才能和创造精神。要恰当地估计文艺的功能,实事求是地分析和看待文艺领域中的是非问题。必须认真贯彻执行百花齐放、推陈出新、洋为中用、古为今用的方针,保障作家、评论家的创作自由和评论自由。在艺术形式上提倡不同形式和风格的自由发展,在艺术理论上提倡不同观点和学派的自由讨论。在提倡创作自由的同时,我们也期望一切正直的、有良知的文艺家为社会的进步、国家的安定团结创作出直接为人民、为社会主义服务的作品。任何对人生、对社会采取不负责任的态度,都是错误的。我们要反对有的人打着创作自由的幌子,把文艺作为一种推行资产阶级自由化的政治工具,诋毁党的路线、方针、政策,否认党的领导。把文艺作品当作宣泄工具的做法是不可取的。一个时期以来,社会上淫秽书刊、录像泛滥,各种低级趣味的文艺作品充斥文艺市场。前一段,把洗脚、孵鸡等搬上中国美术馆的艺术殿堂,并称之为代表新潮流的“行动艺术”,其本质是对艺术的亵渎,对美的摧毁。第三要积极推动和发展健康活跃的文艺评论,要提倡不同风格、不同形式、不同流派的作品展开竞赛。鼓励文艺问题上各种观点的争论。报刊在文艺评论方面,要真正贯彻“两为”和“双百”方针,采取公正的态度,形成一种健康、民主,互相尊重、平等讨论的气氛。第四要探索新的工作方法。各级党委要模范地执行党关于文艺的路线、方针和政策,加强同文艺工作者的交往和讨论,经常向他们介绍情况,同时也听取他们的意见和要求,并尽力为他们深入了解社会生活和从事文艺创作提供必要的帮助。既要坚持原则,又不要横加干涉。但我们不能要求党和政府对文艺完全不加干预,对具体的作品“根本不管”。实际上,任何一个国家的政府和执政党对文艺都不可能完全不加干预,对具体的作品都不可能“根本不管”,区别只在于干预的范围、标准不同,介入的方式、途径不同。事情的关键不在于管的多和少,而在于按什么原则和方向去管。我们是以马克思主义为指南的社会主义国家,党对文艺的指导应坚持党的四项基本原则,着眼于把握总体的政治方向,对具体的文艺观点和文艺作品的评论,文艺作品的优劣、艺术品位的高低,应当由广大群众和文艺家们通过正常的民主讨论去评判。要相信人民群众的艺术鉴赏力和审美能力。处理学术和艺术中的矛盾和争端,应当尽可能避免用行政命令的方式,应当学会通过民主的、平等的讨论,来求得认识的深化和艺术水平的提高。要通过发展健全的物质文化条件和适当的舆论环境,制定和实施有关的规章制度、必要的法律条款以及各种文化方面的经济政策,来提倡正确的东西,纠正不正确的东西,抑制消极、保守的东西,促进文学艺术的健康发展。