Interview with Zhou Wenxing: Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations in the Next Few Years—Is War Inevitable?

China and the INF: Is there a Future for U.S.-China Arms Control?

By Raphael J. Piliero.

When envoys arrived in Vienna in July, the table was set for arms control negotiations between the US and Russia on strategic nuclear weapons, transparency and confidence building measures, and the emerging threat posed in outer space. Yet, while only the US and Russia were present, the table was set for China to join – literally, as well as figuratively. Reports indicate that US arms-control envoy Marshall Billingslea set up seats for China, accompanied with Chinese flags, despite knowing that China had declined the invitation – he proceeded to post on social media an image of the empty Chinese seats, claiming the display demonstrated an unwillingness of China to come to the table.

Theatrics aside, the bilateral conference in Vienna raises an important question – what explains China’s reticence to take part in nuclear arms control negotiations? At this point, the vast majority of nuclear arms control agreements have been between the US and Russia, ranging from the SALT treaties beginning in the 1960s to the INF of 1987 and the various forms of START from the 1990s to the present.

China’s lack of participation in arms control hasn’t been for lack of effort by the US – numerous overtures have been made, but China has been adamant that nuclear discussions should remain bilateral – between the US and Russia. Believing the Chinese force to be “an order-of-magnitude” smaller than their counterparts in the US and Russia, China has claimed that those countries should “take the lead” for the foreseeable future. Upon further reductions, then China might be willing to come to the table.

This has been echoed in numerous statements by officials high up in the Chinese government. In 2019, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang reiterated that Chinese involvement would succeed Russian and American reductions first, claiming that the country’s nuclear forces were at the “lowest level” possible while maintaining a survivable posture. Geng claimed that “China opposes any country talking out of turn…and will not take part in any trilateral negotiations on a nuclear disarmament agreement.” In 2020, the sentiment was reaffirmed, with a foreign ministry spokesman saying that “China has repeatedly reiterated that it has no intention of participating in the so-called trilateral arms control negotiations.”

From a quantitative standpoint, China’s hesitation seems well-warranted – there exists a huge asymmetry between Chinese nuclear capabilities and those held by Russia and the US. The US and Russia each have around 1300 strategic deployed warheads; Russia has over 4300 stockpiled warheads, while the US has over 3800. No official counts exist of Chinese stockpiles, which makes estimations a challenge. However, China likely has around 320 stockpiled warheads (which are not actively deployed, as China maintains a no first use policy and keeps warheads demated).

To make sense of this discrepancy, one must look to the differences that exist in Chinese nuclear strategy when compared to the US or Russia. While both the US and Russia retain the options of a first strike (and envision counterforce targeting to limit the nuclear weapons of an adversary at the early onset of a crisis), China envisions their nuclear arsenal to be primarily defensive. Envisioning a “lean and effective” nuclear deterrent, China has committed itself to a no first use policy, maintaining only enough nuclear weapons to launch a retaliatory strike if another nation initiates nuclear provocations. For the past several decades, China believed that having several hundred nuclear weapons would suffice to launch a devastating counter-attack in the face of a preemptive strike.

However, the possibility remains that this calculus is changing for China. The US has worked extensively with allies in Asia on Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD), which aims to intercept ballistic missiles as they are launched against a defending country. In Asia, one BMD project of note is the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) program, deployed in South Korea beginning in 2008. Ostensibly for use against North Korea, China has long feared that such a program is actually meant to neutralize the ability for China to launch a retaliatory strike. Here, China fears that the US would initiate a preemptive strike against China, using counterforce targeting to eliminate a sizable portion of CHinese nuclear weapons. While China would have weapons left over to fire off a devastating retaliatory strike, US BMD would mop up the remaining missiles, rendering the US unharmed, leaving China without a viable option to retaliate. Russian experts claim that since the 1960s, China has produced enough uranium and plutonium for 3600 nuclear warheads, with the vast majority being held in stocks. If China feels the need, this could spur a “sprint to parity” – American experts, such as Robert Ashely with the Defense Intelligence Agency, have predicted that China would “at least double the size of its nuclear stockpile” over the next decade.

Fundamentally, this fear highlights a doctrinal difference between the approaches of the US and China. The US views BMD as a fundamentally defensive addition, protecting the homeland from nuclear strikes that adversaries could deliver. In contrast, China places a premium on maintaining mutually assured destruction – the knowledge that both sides can truly destroy the other creates crisis stability. BMD disrupts such stability – it makes the US invulnerable to Chinese responses, which legitimates American aggression in a nuclear conflict. Many have argued that China’s fears are in part driven by a US refusal to acknowledge “mutual vulnerability” to China’s ability to inflict unacceptable damage on the US.

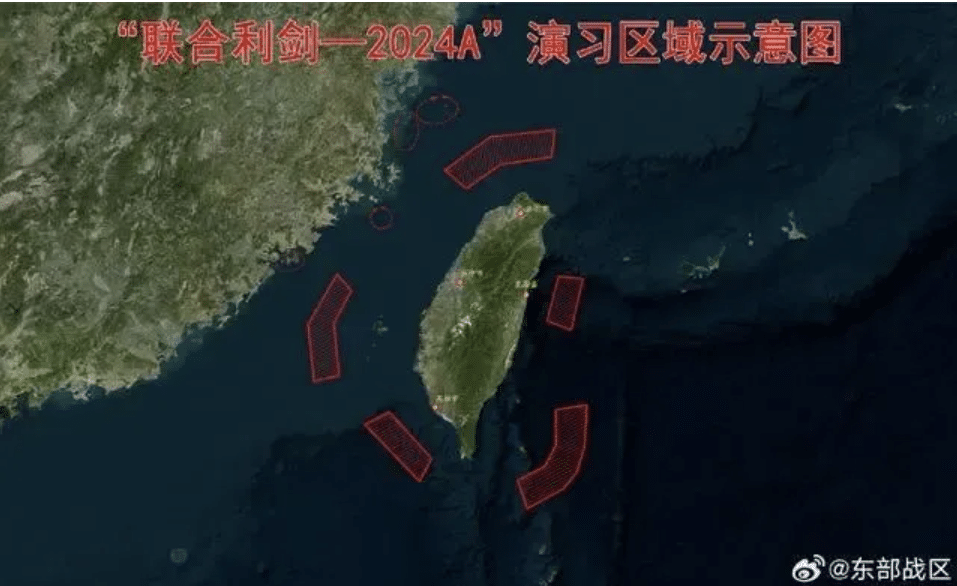

China’s intransigence on nuclear arms control leaves the US in a dilemma – while the US pursues reductions with Russia, China remains in a no man’s land, with zero restrictions on their nuclear production. While a future “sprint to parity” remains the biggest fear, there have already been ways that the lack of arms control has benefited China. While the US and Russia were bound by the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), China developed a myriad of medium range missiles that would be in violation of the treaty – studies estimate that 90% of their rocket forces would run afoul of the INF. These missiles pose a particular problem for regional allies – medium-range missiles are frequently mentioned as being directed at Taiwan, were a military provocation to exist between the two adversaries.

To both prevent future Chinese developments and limit Chinese medium-range missiles, China must be brought to the negotiating table for trilateral arms control. Yet, China’s refusal has seemed categorical, and with good reason – why should they negotiate with countries that possess arsenals several orders-of-magnitude larger than their own?

Instead of viewing the Chinese refusal as the nail in the coffin of trilateral arms control, the US should consider what motivates Chinese reluctance, and take steps to meet China halfway. The reason China is reluctant to reduce their arsenal is two-fold – the overwhelming advantage that the US and Russia hold with regards to strategic forces, and the fear that a smaller arsenal would compromise survivability. In approaching China, the US should take a number of steps.

First, the US and Russia should be willing to make asymmetric reductions on strategic forces. A tit-for-tat strategy of reductions would be a non-starter, as China has a fraction of the strategic forces possessed by their American and Russian counterparts. Instead of allowing China to “build up” to the level allowed by New START (a recipe for proliferation), Russia and the US should “build down” and find a level in between China’s current level and the amount allowable by New START.

This should not be taken as a green light for Chinese proliferation – China is not mandated to build up to that level. Instead, it serves as a hard ceiling on Chinese arsenal expansion – while previously China had no theoretical cap, they may now not extend past this limit.

While this ostensibly seems like a win solely for China, the US and Russia derive a clear benefit – the codification of a limit on the Chinese arsenal, as well as corresponding transparency. Previously, Chinese build-ups could be open-ended, but now would be limited by a specific, numerical cap. Additionally, arms control requires enforcement and verification, which would necessitate Chinese disclosure of the precise contours of their nuclear arsenal (as well as submission to an inspections regime). This would provide their counterparts some much-needed transparency, enhancing stability.

Second, the US should propose reductions in intermediate-range missiles, restoring a modified version of the INF framework. Just as the US and Russia would make the majority of the cuts in strategic forces, China would make the majority of the cuts with intermediate range forces; however, China would secure a guarantee that the US and Russia would not build up to their level, providing an assurance against an arms race. Even with the greater number of Chinese cuts, China would derive a clear benefit from the assurance that the US wouldn’t be building and deploying intermediate-range missiles in Asia, a concern of China’s following the withdrawal from the INF Treaty.

To further sweeten the pot, the US could offer asymmetric reductions in air-launched intermediate range missiles. While China has the clear advantage in ground-launched intermediate-range missiles, Russia and the US have a leg up with the air-launched variety. Chinese asymmetric reductions in ground-launched missiles could be traded for asymmetric Rusisan and US reductions in air-launched missiles.

Third, the US should recognize the differences in how China conceptualizes deterrence, and work to meet them halfway. While the US views BMD as a defensive, stabilizing force, China views it as something that undermines mutually assured destruction. In particular, China has voiced concerns about the effects of THAAD on a Chinese assured second strike. While eliminating THAAD or other forms of missile defense would be an unacceptable option for the US and allies, the US can have its cake and eat it too. THAAD would have little potency against China, with an operational range of solely 125 miles – the primary fear from China is about improvements to it and the open-ended nature of US BMD. The US should allow China access to data about BMD, including THAAD to verify that the capabilities would not pose a threat to Chinese missiles, and only to those of nations such as North Korea. This would assuage Chinese concerns about BMD, without compromising such systems against rogue nations.

Similarly, the US should acknowledge mutual vulnerability with China. This would be a small but important symbolic step to reassure China that the US does not view themselves as invulnerable in the event of a US first-strike against China. This may reassure China that their current arsenal is sufficient for deterrence, and that there is no need for further build-ups, perhaps paving the way for reductions.

One obvious barrier could be Russia – after all, trilateral arms control would be impossible if one of the parties preferred the existing bilateral framework. However, Russia has made clear that they have interest in multilateral arrangements. Putin claimed in 2012 that “All nuclear powers should participate in this process,” indicating an openness to a broader framework.

Another barrier could be US domestic interests, particularly in an election year. However, this may be popular across the aisle. President Trump has been pushing to make New START into a trilateral agreement, holding out on signing an extension with Russia to see if China could come to the table. If President Trump is defeated, the prospects for trilateral arms control may be even stronger, as Democrats have traditionally been more in favor of arms control than their counterparts in the Republican Party.

Yet, despite the compromises that the US can offer, the possibility remains that China will keep on saying no. As evidenced by the recent congressional testimony of Stephen Biegun, The two envision each other as strategic competitors, and disagree on everything from intellectual property and trade policy to the status of Taiwan and responses to Hong Kong. Doing arms control will be hard to disentangle from the broader strategic relationship, and China may prefer to hedge against the US by building up an ever-larger arsenal.

Yet, Biegun also highlights the areas in which the US and China have managed to find common ground, despite protracted difficulties – responses to COVID-19, diplomacy as it relates to North Korea, cyber norms, and more. Arms control with the Soviet Union was able to flourish during the darkest times of the Cold War, and it shouldn’t be ruled out with China, either. Statements by China regarding arms control have slowly but surely grown to be less categorical in their rejection of arms control – while at one point China claimed that they would “never participate in [trilateral arms control],” by June 2019 after the INF collapsed China gave a caveat, claiming that “Right now we do not see any condition or basis for China to join…”

Even if arms control cannot happen overnight, the groundwork can be laid for it now. Whether hosting Track II dialogues about strategic stability, exchanging missile pre-launch notifications, or acknowledging mutual vulnerability, many steps can be taken now for the US to demonstrate good faith to China and an interest in finding areas of common ground. Perhaps then, at the next conference in Vienna, desks with Chinese flags will also be accompanied by Chinese diplomats, instead of remaining empty.

Raphael J. Piliero is a senior at Georgetown University pursuing a bachelor’s degree in Government. He has also written publications on domestic political issues for outlets such as Political Wire, and previously served as a legislative intern for the chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. A member of the Georgetown Policy Debate Team, he and his partner were a top 16 team in the nation in 2020.

The views expressed are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of The Carter Center or its associates.