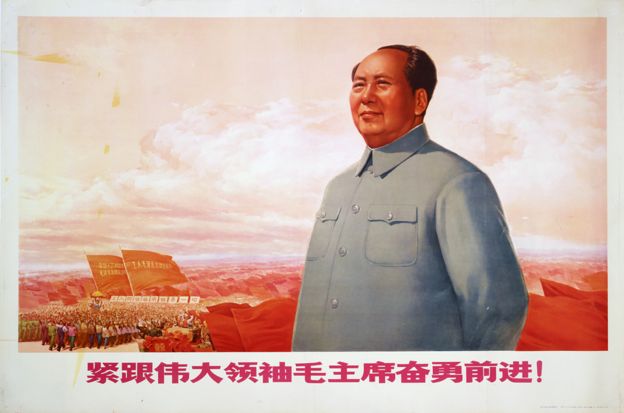

China’s Curious Cult of the Mango

Fifty years ago, China was plunged into the most chaotic and traumatic decade of its recent history – the Cultural Revolution. During this period, the nation was gripped by a peculiar hysteria: a mania for mangoes. Benjamin Ramm discovers how the fruit became an object of deep veneration, and a vehicle for the promotion of the cult of Chairman Mao.

In 1966 Mao had called on the student Red Guards to rebel against “reactionary” authorities. His aim was to reshape society by purging it of bourgeois elements and traditional ways of thinking. But by the summer of 1968 the country had become engulfed in fighting, as Red Guard factions competed for power.

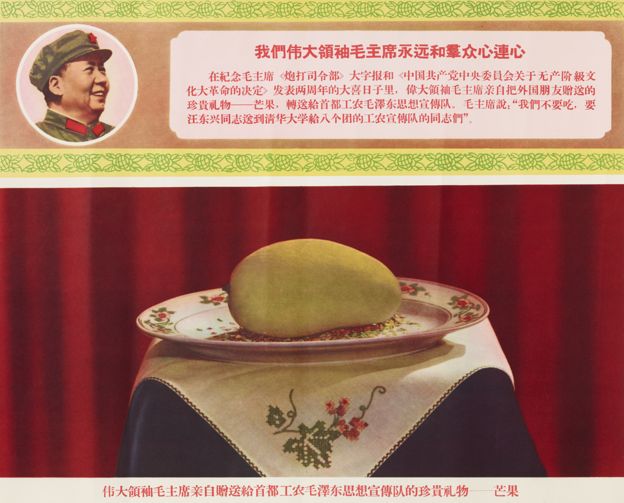

To quell the forces that he had unleashed, Mao sent 30,000 workers to Qinghua University in Beijing, armed only with their talisman, the Little Red Book. The students attacked them with spears and sulphuric acid, killing five and injuring more than 700, before finally surrendering. Mao thanked the workers with a gift of approximately 40 mangoes, which he had been given the previous day by Pakistan’s foreign minister.

They had a huge impact.

“No-one in northern China at that point knew what mangoes were. So the workers stayed up all night looking at them, smelling them, caressing them, wondering what this magical fruit was,” says art historian Freda Murck, who has chronicled this story in detail.

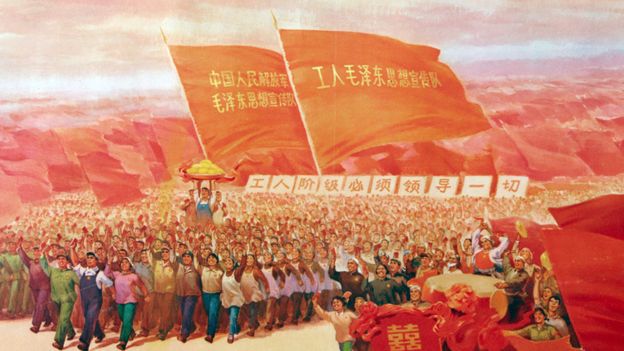

“At the same time, they had received a ‘high directive’ from Chairman Mao – saying that henceforth, ‘The Working Class Must Exercise Leadership In Everything’. It was very exciting to be given this kind of recognition.”

This power shift – from the zealous students to the workers and peasants – offered respite from the anarchy.

“Some people in Beijing told me that they perceived that Mao had finally intervened in the chaotic random violence, and that the mangoes symbolised the end of the Cultural Revolution,” Murck says.

Mao’s Cultural Revolution

Zhang Kui, a worker who occupied Qinghua, says that the arrival of one of Mao’s mangoes at his workplace prompted intense debate.

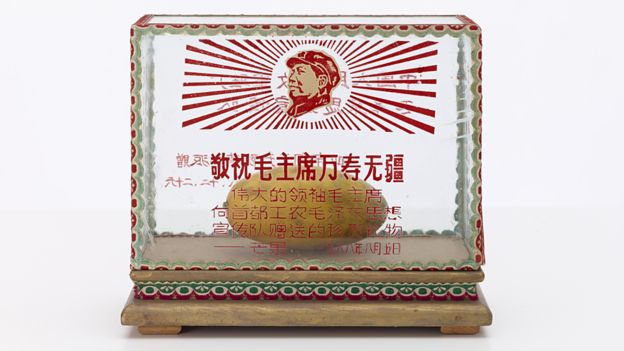

“The military representative came into our factory with the mango raised in both hands. We discussed what to do with it: whether to split it among us and eat it, or preserve it. We finally decided to preserve it,” he says.

“We found a hospital that put it in formaldehyde. We made it a specimen. That was the first decision. The second decision was to make wax mangoes – wax mangoes each with a glass cover. After we made the wax replicas, we gave one to each of the Revolutionary Workers.”

Workers were expected to hold the sacred fruit solemnly and reverently, and were admonished if they failed to do so.

Wang Xiaoping, an employee at the Beijing No 1 Machine Tool Plant, received a wax replica. The fruit itself was destined for higher things.

“The real mango was driven by a worker representative through a procession of beating drums and people lining the streets, from the factory to the airport,” says Wang.

The workers had chartered a plane to fly a single mango to a factory in Shanghai.

When one of the mangoes began to rot, workers peeled it and boiled the flesh in a vat of water, which then became “holy” – each worker sipped a spoonful. (Mao is said to have chuckled on hearing this particular detail.)

“From the very beginning, the mango gift took on a relic-like quality – to be revered and even worshipped,” says Cambridge University lecturer Adam Yuet Chau. “Not only was the mango a gift from the Chairman, it was the Chairman.”

This association is reflected in a poem from the period:

Seeing that golden mango / Was as if seeing the Great Leader Chairman Mao!

Standing before that golden mango / Was just like standing beside Chairman Mao!

Again and again touching that golden mango: / the golden mango was so warm!

Again and again smelling the mango: / that golden mango was so fragrant!

The mangoes toured the length and breadth of the country, and were hosted in a series of sacred processions. Red Guards had wrecked temples and shrines, but destroying artefacts is easier than erasing religious behaviour, and soon the mangoes became the object of intense devotion. Some of the rituals imitated centuries of Buddhist and Daoist traditions, and the mangoes were even placed on an altar to which factory workers would bow.

China has a long history of symbolic associations with food, which may have encouraged extravagant interpretations of Mao’s gift. The mangoes were compared to Mushrooms of Immortality and the Longevity Peach of Chinese mythology. The workers surmised that Mao’s gift was an act of selflessness, in which he sacrificed his longevity for theirs.

Little did they know that he disliked fruit. Nor were they concerned to learn that Mao was simply passing on a gift he had already received. There is a tradition in China of zhuansong, or re-gifting. It may be regarded as vulgar in the West, but in China re-gifting is widely seen as a compliment, enhancing the status of both the giver and the recipient.

The mangoes also proved to be a gift to the propaganda department of the Communist Party, which quickly manufactured mango-themed household items, such as bed sheets, vanity stands, enamel trays and washbasins, as well as mango-scented soap and mango-flavoured cigarettes. Massive papier-mache mangoes appeared on the central float during the National Day Parade in Beijing in October 1968. Far away in Guizhou province, thousands of armed peasants fought over a black and white photocopy of a mango.

But not everybody was so enthusiastic about the fruit. The artist Zhang Hongtu told me of his scepticism.

“When the mango story was published in the newspaper, I thought it was funny, stupid, ridiculous! I’d never had a mango, but I knew it was a fruit, and any fruit will rot.”

Those who expressed their doubts, however, were severely punished. A village dentist was publicly humiliated and executed after comparing a “touring” mango to a sweet potato.

The mango fever fizzled out after 18 months, and soon discarded wax replicas were being used as candles during electrical outages.

On a visit to Beijing in 1974, Imelda Marcos took a case of the Philippine national fruit – mangoes – as a gift for her hosts. Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, known as “Madame Mao” in the West, tried to replicate the earlier enthusiasm, sending the mangoes to workers. They dutifully held a ceremony and gave thanks, but Jiang Qing lacked her husband’s sense of political timing.

The following year, as Mao lay ill and with no clear successor in sight, she commissioned a new film, Song of the Mango, to enhance her credibility. But within a week of its release, Jiang was arrested and the film was taken out of circulation. It was the final chapter in the mango story.

Now mangoes are a common fruit in Beijing, and Wang Xiaoping can buy “golden mango” juice whenever she likes.

“The mystery of the mango is gone,” she tells me. “It’s no longer a sacred icon as before – it’s become another consumer good. Young people don’t know the history, but for those of us who lived through it, every time you think of mangoes your heart has a special feeling.”

Mao, like the mangoes he gave the workers, now lies preserved in wax in a crystal glass case.

Historians have tended to regard the mango craze as a bizarre fad, but it is one of the few occasions when culture was created spontaneously from the bottom-up, initiated and interpreted by the workers. During a period of great cruelty, the mangoes represented for people an emblem of peace and generosity. They wanted to believe the promise written on the enamel trays: “With each mango, profound kindness.”

Feb. 11, 2016 on BBC News.

Read more here